Artist Unknown

An artist's identity is so important for interpretation and understanding of cultural context. But what about when we don't know who they were?

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

As much as I enjoy (and encourage) looking at a work of art and forming first impressions before absorbing any contextual information about the work, I also love learning more about the artist. Where did they live? How old were they when the work was made? What were their inspirations, and why did they create this piece, and at that moment in history? How long did the work take the complete?

But sometimes, particularly when studying antiquity, none of these questions are able to be answered because we simply don’t know who created the work. How does the absence of the artist’s identity change the way we interpret a work? Does it change anything? This is the topic of this week’s newsletter.

Artist unknown

To start to address this topic, it is important to note that the definition of “artist” has evolved over time. In antiquity, for example, there were certainly prominent artists, such as the sculptor and painter Phidias, most famous for his giant statue of Zeus at Olympia. But in the case of many objects now considered to be “ancient art,” there is no known author and no signature, inscription, or mark to signify who the creator was. In many cases, it seems that the creator was thought of more as an “artisan” or “maker” as opposed to an “artist,” a subtle but impactful difference. Nevertheless, examples of such works show what seems to me to be the same level of skill and care as an artist would show. What comes to mind is Ancient Greek and Roman funereal portraits, like the one below:

Museum descriptions of works can be rather straightforward, but I especially love the one the Met gives for this piece (author unknown):

This noble image of a woman brings to mind the philosopher Aristotle's description of commonly held beliefs about the dead: "In addition to believing that those who have ended this life are blessed and happy, we also think that to say anything false or slanderous against them is impious, from our feeling that it is directed against those who have already become our betters and superiors" (Of the Soul, quoted in Plutarch, A Letter to Apollonius 27). Larger than life and seated on a thronelike chair, this figure assumes almost heroic proportions.

Her expression of tranquility and contemplation seems remarkable to me somehow; the artist—whoever they were—managed to capture the defining look of someone who must have been especially thoughtful. The curve of her arm almost reminds me of a hug, giving her an added impression of warmth. The drapery of her clothing is realistic or maybe hyperrealistic and also adds to this sort of coziness that she exudes. Whether or not this was actually the case, the artist of the portrait has, as the (unknown) Met writer points out, crafted an image of someone who seems beyond pain in the afterlife—and indeed to have been a better person than the rest of us even when she was still alive. She is lifelike, but also larger than life, and the presence of her image strikes a contrast with the fact that the woman herself is no longer with us. Ultimately, we do not need to know the maker’s identity to feel the impact; their skill is known by the aesthetic and emotional qualities of their work.

All the same, I feel I would like to know who brought this woman back to life in her funeral portrait. What was their process? Did they ask the family for details so that they could provide an accurate rendition? Or is she one of a certain “type,” nonspecific but broadly applicable to any number of deceased women? In other words, as we just saw, the lack of an artist’s identity is not really a hindrance to the interpretation of the work, but it does raise certain questions. The author’s identity is almost like the “lost whole” of the fragmented works I talked about in last week’s post: we idealize and are intrigued by the missing part.

The loss of the artist is not insurmountable for the work, and indeed this may well be the point of creating art at all: it outlives the artist. In many instances, the work itself does in fact reflect the realities of the artist’s life, whether we know anything specific about the artist or not. One such example that comes to mind is this piece from Hellenized Iran in the 2nd-century BCE:

Though not on view, I had the good fortune to see this piece in person a couple of years back when I participated in the Getty Consortium Seminar and I’m still thinking about it. This piece would go on a horse’s bridle as a sort of decoration for the horse. A piece like this would have been made in a workshop—obviously there wasn’t mass production like there is in the modern era, but there was an industry of sorts. In the center is a Siren from Greek mythology, a bird-footed woman with such a beautiful voice that it could convince sailors to jump off their boats and try to swim to shore (often dying in the attempt). At the top is a Near Eastern mythological creature called a Lamassu, a protection deity which has a human head, a lion’s body, and eagle’s wings. At the bottom is an eagle attacking a deer, which was a relatively common motif in Central Asia at the time.

The combination of cultural traditions makes a striking image: the Lamassu might protect the wearer and his rider, while the eagle attacking the stag would indicate what the horse-rider pair could do to its enemies. The siren is an interesting addition; it could be a symbol of the danger an enemy would be in if it encountered the wearer; the enemy in question might take it as a warning to flee, not draw closer and engage.

It could be that this piece was for a Parthian patron; the Parthians had a smallish empire that spanned modern-day Iran and other parts of the region, and they adopted many Greek features into their art and clothing. We can’t know the maker of the piece, but we can tell that they drew from a range of source material for inspiration. So, in a way, we do know who they are, just not their name.

Artist unknown?

It’s not just antiquity that has left us works of art without a firm identity for the artist. Just like the bridle piece above, however, it is often possible to see the influence of someone whose name is known to us. Early modern works without firm attribution to a specific author are sometimes classified as “workshop of” a known, established artist. This generally happens because a student’s style will be similar to their mentor’s. For example, here’s another 16th century image of our friend Bacchus, whom we saw last week:

The Louvre attributes this to “an anonymous south German artist,” though it was formerly attributed to Peter Vischer the Younger, who primarily worked in bronze-cast sculptures but also made illustrations. I’m not sure why scholars at the Louvre decided to un-attribute it to Vischer, but maybe there was just something off about it compared to his other works (which, as we saw last week, can make a work very intriguing indeed!).

I like the slightly unfinished vibe of this drawing, like it was just a quick sketch by the artist. Maybe they meant to come back to it, or maybe it was just meant to get their creativity flowing. It seems like possibly this could have been done by one of Vischer’s students; it might show his influence rather than revealing the work of his own hands. In this case, the ambiguity of the artist becomes less important; this example also highlights how a good teacher shapes the work their students do.

The artistry of everyday objects

The more I got to thinking about the subject of anonymous artists, the more it occurred to me that we are surrounded by artist-unknown objects of great aesthetic quality in our everyday lives. Sometimes we do know: someone in our family took the picture on the wall, a local potter made the coffee mugs, a friend knitted the blanket hanging over the back of the couch. But so often in the mass-production era the person who designed an object is unknown and unknowable, especially as trends continue on and on.

Of course, in previous eras there were no factories, but there were certainly artisans and workshops following the trends of the day. For example, in prehistoric Greek art, animals were all the rage for small household items, like this vessel:

Although we will never know who made this, I want to acknowledge their careful rendering of the animal, which looks sort of like a deer or potentially a goat. Whatever it is precisely, it is clear the artist felt it was a nice enough animal to depict, right down to the geometric texture added to give an impression of fur. Maybe they even realized it was not so lifelike, and laughed at the animal’s elongated body and exaggerated features. It would be great to know also why the vessel has only three legs when the creature in question indubitably had four (unless?). I bet this vessel made its owner smile every day. I like to think the creator of this piece had a good sense of humor as well.

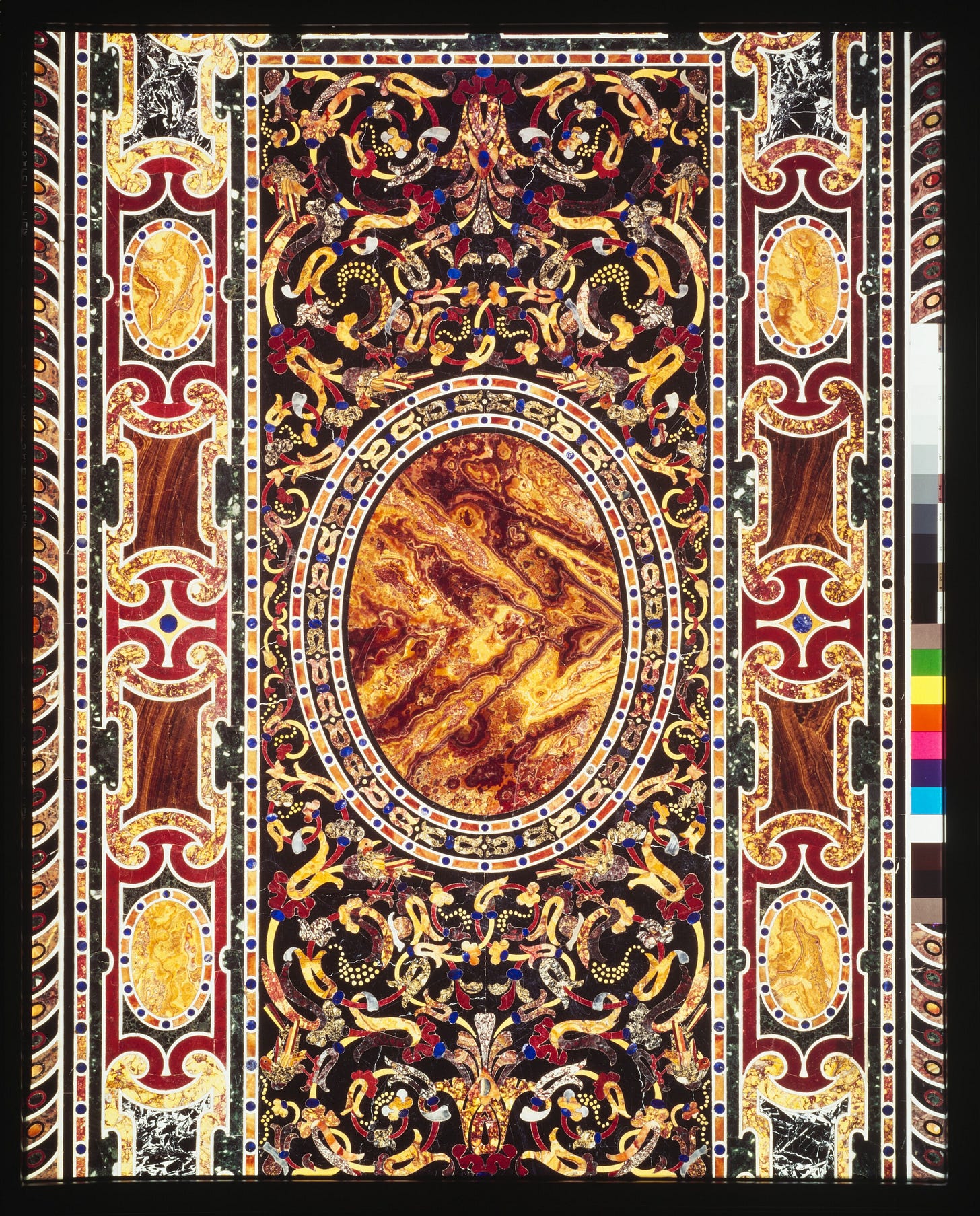

Jumping forward a few millennia, sometimes even the most opulent pieces have no known artist either, like this early modern table top from an Italian villa:

The colors and intricate pattern on the table top really stand out. It’s almost unimaginable how long it would have taken to even acquire the materials for this piece, let alone actually make it. I have a feeling this was probably a collaborative effort in terms of the making itself, but who was the designer?

Like the maker of the animal vessel from prehistoric Greece, they too found inspiration in nature: if you look carefully, you can see birds (and snails!) among the foliage. We can only see the results of the artistic process, which must be good enough.

Local artists

To conclude, I was also thinking about smaller local artists without a social media presence whose names are known to us but not a whole lot else. In my parents’ house, there’s a small doll/figurine of an angel hanging on one of the doors. I love the way her wings are rendered with ribbon and how she has a medallion around her neck that says IMAGINE.

The piece has a tag on it, handmade and hand-painted, that reads “Handmade by Julie Ann Wood.”

While we know Julie Ann Wood’s name, she still remains an enigma: try as I might, I could not find any mention of Julie Ann Wood online; my parents acquired this particular example from a small shop no longer in business. Although I was unsuccessful in finding out more about the artist, I was heartened to think of all the other artists out there even now, perhaps mostly unknown, but creating the most sublime works. Sometimes we don’t know the artist’s name, but can figure out a lot of information about them, and sometimes we do know the artist’s name, but they remain elusive nonetheless.

Thank you for reading!

Thank you so much for reading! As always, I would love to hear your thoughts. Take care until next time.

MKA