Some Blemish

When art is perfectly imperfect, whether there are actual mistakes, portrayals of broken things, or just questionable stylistic choices

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

The Roman poet Ovid was known for his outlandish subject matter and colorful writing style. According to Seneca the Elder, a commentator on rhetoric, Ovid was well aware of his tendency to be over-the-top, and was by all accounts overly in love with his own talent. But I think this “shortcoming” makes Ovid one of the most interesting writers to read. And maybe he had a point: Seneca writes that Ovid “used to say sometimes that a face looked better if it had some blemish (literally ‘mole’) on it” (aiebat interim decentiorem faciem esse, in qua aliquis naevus fuisset, 2.2.12).

I know Ovid is talking in metaphorical terms—though he did love writing about love, so maybe it wasn’t totally figurative—about rhetorical style, but I think his point applies to the visual arts as well. Sometimes odd details, flaws, elements that stand out in just the wrong way, or representations of brokenness actually make a piece more intriguing to look at. Seneca’s point about Ovid was that sometimes the parts that critics deem to be the worst part of a work are sometimes the artist’s favorite—and, maybe, sometimes the audience’s favorite as well.

Flaws

If you walk around a museum, it might be easy to think that artists just produce amazing work right from the get-go. But, in fact, they all had to deal with less-than-great first drafts, just like the rest of us. The Getty has a great feature on artists’ mistakes and do-overs, focusing on early drafts of work by Rembrandt and others. You can also find plenty of discussion online about famous works of art with various mistakes or oversights. But what I’m interested in is the ways in which less-than-ideal features of a work make it all the more intriguing.

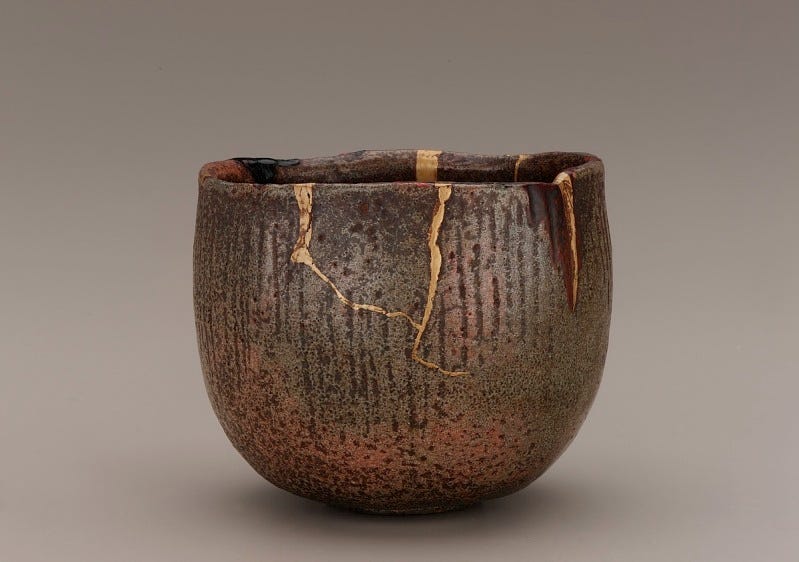

What came to mind when I first started thinking about this is the Japanese practice of repairing broken pottery with gold, which then makes a new kind of design on the piece.

I also love this technique because it makes the point that even mundane, everyday objects are worthy of great care—and that level of care can elevate such things into a work of art.

The allure of fragmentation

The phenomenon of being fascinated with the flawed, broken, or otherwise imperfect extends to whole other genres and eras. In the eighteenth-century painting “Landscape with Classical Ruins and Figures,” we see a scene filled with the ruins of the ancient world.

The painting almost reads like a still life, or at least there’s a sense of calm that comes from the ancient ruins and the still marble figure perched under the obelisk. But then the eye travels down to the titular “figures” of the scene, and gradually we forget the Roman architecture, which is not so much abandoned as in the process of revitalization. The Romans may be long gone—what looks to be a large sarcophagus lilts off to the side in the lower left-center of the scene, emphasizing their gone-ness—but others have come in to take their place. There’s a man with a dog, a mother with a child, some people who look to be making an attempt to scale the ancient wall, and others. The painting may be evocative of Roman power, but the living figures slowly draw our attention until the impression of antiquity’s looming presence is taken over by modern curiosity about antiquity. The Romans’ abandonment of their monuments has left a place for posterity.

My eye also goes to the tree in the center of the scene, curving off to the right side and whose orange leaves perhaps make the viewer think of autumn. The overgrowth of plants on many of the ancient ruins further points to the fact that nature is taking over these monumental buildings, a stronger power. This is the “mole,” the blemish that makes the architecture even more intriguing than the unflawed originals, which would have been richly painted and, obviously, unbroken. But perhaps we like the ruin more just as it is; better to leave the statue broken and the temples overgrown with branches than to restore an artificial image of some long-lost ideal that may not have really existed and whose precise features are difficult or impossible to ascertain.

One of my favorite discussions on the fragments of antiquity comes from a volume called, aptly, The Fragment: An Incomplete History. In his essay from this collection, Glenn Most writes (2009: 18):

Real wholes are ephemeral and start falling apart even before they are finished. Their fragments last much longer and yet they too are subject to decay and corruption. The only thing that is truly immortal is the lost whole that we reconstruct on the basis of fragments, that never existed in reality, and that therefore can never perish. However splendidly the fragment gleams, what fascinates us even more is the darkness surrounding it.

Do the figures in the landscape feel the pull of the “lost whole,” or is antiquity so far outside their scope of experience that they have no context for what the original might have looked like? By exploring the ruins, are they playing at being Romans, or are they merely living out their daily lives? It’s hard to be sure, but it also seems to be that, here, the whole retains its immortality but is not lost.

Striking features

Another category that might be relevant to our discussion is the work that has a certain striking feature to it without it being flawed, some asymmetry or other jarring element that takes away from the impossible standard of “perfection,” but makes it somehow better than perfect. The example that comes to mind for me is Brugghen’s Bacchante with an Ape. A bacchante is a female follower of the god Bacchus or Dionysus, the Greco-Roman god of wine, madness, and theater (particularly tragedy). The description notes that there is something disturbing about the painting, identifying it as the way she gazes at the viewer. I’m not sure it’s the gaze. It’s maybe a bit hard to tell in the picture, but in real life, the brightness of the bacchante’s pale skin leaps off the canvas, making a very striking contrast with her red garment.

I also think there’s something about the way the bacchante is squeezing a bunch of grapes into her drinking cup. I’m no vintner, but I’m pretty sure this is in fact not the best practice for making wine. The odd and impetuous behavior of the bacchante gives me a jolt when I look at the piece, but somehow that makes me like it all the more. She doesn’t care what others think about her.

This is probably for the best: apparently, the ape might be judging her for drinking so much—or, to be more precise, symbolizing the moral stance of condemning excessive wine consumption. We know Dutch artists love their symbolism (here for it!). But the bacchante’s can’t-stop-won’t-stop vibe completely overshadows the ape, who is about to bite into a bunch of grapes, which is probably the closest an ape can get to embracing the “if you can’t beam ‘em, join ‘em” mentality. But, all in all, I think the jarring aspects of this work make it so much more fun to look at.

Apparently, the artist was inspired by the work below, a portrayal of Bacchus himself.

The similarities are fairly clear, right down to the similarly-shaped wine cup held in the left hand of both figures. But it seems he even adapted the slight oddness of Caravaggio’s piece, because this too has some elements that jar the viewer, making it perfectly imperfect. Here, the contrast between Bacchus’ youthful face and overly muscular arms is what catches my eye, as well as the contrast between his red face and hands and his pale body (in general, Bacchus is portrayed as either drunk or in the process of getting drunk, as one does if one is a wine deity). The giant headpiece fall foliage is giving Midsommar, but Caravaggio couldn’t have known that. Still, there’s something slightly off about Bacchus. Maybe it’s the fact that his powers also encompass madness, the possibility of existing in an altered state of consciousness. While Bacchus gave humanity wine, which the Greeks thought took as compensation for the overall wretchedness of mortal life, he also brings insanity upon the unlucky.

Despite the ambiguity of his expression, there’s something a bit reserved about Bacchus here, an aloofness that the bacchante does not share. The scene is not composed, but in its jarring lack of harmony it is all the more charming.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter!

Although I am no fine artist, I am no stranger to creating imperfect things. One of these many things is a quilt I recently made, and somehow got all the way to the end of the project without noticing that two pieces of a block were upside down:

Would I rather it was flawless? Maybe. But, then again, maybe not. I’ve come to appreciate the way an imperfection can actually protect us from a boring state of perfection that would ultimately take away from the intrigue of the work.

Thank you for reading this week’s edition of Reading Art! Take care until next time.

MKA