What Statues Hide: The Personality Lurking Behind Every Portrait

Some thoughts on the connections between art, portraiture, and life writing

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

Last week was a busy one of teaching my Ancient Greek class at UCLA and continuing to get back in the swing of things in the Scholars Program at Getty. The typesetters of Classical Quarterly sent me the proofs for my first article! So I spent some time this week going through and making sure everything looks good before it finally gets published. It’s on the carefully arranged letter books of not-yet-Emperor Marcus Aurelius (aged 18 to mid/late 30s in these letters) and his close friend and rhetoric teacher, the celebrated orator and politician Fronto.

It looks so ~professional~ all laid out:

These letters are truly fascinating on their own, plus they have a fascinating history. Originally, they were preserved a book. Later, at some unknown point in history, that one book got chopped into two halves, because paper was expensive: these two new books were then reused for a different text; the original letters of Fronto and Marcus (composed in the mid-100s CE) were erased and written over with different texts that were deemed more important, made into what’s known as a “palimpsest” codex.

But in the early 1800s, Cardinal Angelo Mai, a renowned humanist, hit the jackpot: he discovered the first half in the Ambrosian library, then the second one in the Vatican.

Now, most of the letters are lost; things don’t survive super well when they’ve been erased and written over. But we have a lot more of young Marcus than we would otherwise have had, for he would otherwise have been known only by his Meditations, a Stoic work composed later in his life.

These letters are so interesting for so many reasons: they provide a closer look into Marcus’ early life and personal relationships, offer numerous examples of Fronto’s elaborate rhetorical style, which would otherwise have been lost to us because of gaps in textual transmission, and, perhaps most simply, they feed the fascination of reading personal letters made public—especially those of such an interesting person as Marcus Aurelius, the paragon of Stoic virtue and basically a household name today.

For today’s virtual gallery tour, I want to expand our definition of “art” to include not only the images of Marcus and Fronto that remain to us, but also the thoughts, impressions, and feelings that they themselves left behind in their letters. Letters are important! They are themselves art, when you stop to think about it. Think of Fragonard’s lovelorn girl from last week, exchanging letters with her beloved. Think of a postcard, letter, or holiday card that especially touched you, written by hand with a personalized message just for you. These things, to us, are also art. (See, e.g., Janet Altman’s 1982 landmark work Epistolarity: Approaches to a Form). Even Fronto and his family knew this. Just think about it: the reason we even have any letters at all is because he (or his family) decided to keep them and not throw them away.

But how do literary and literal images of a person intersect? To explore this question further, we’ll look at portraits of Fronto and Marcus and then look at the texts they left behind, a deeper look into what I would consider to be the personality that a formal portrait can both reveal and keep hidden—unless you know where and how to look.

Let’s start with Fronto. So little is known about him! And yet, so much. In antiquity, he was thought of as approaching the eloquence of Cicero. His speeches were apparently the stuff of legend. Some of them are recorded in the letters Mai found. Unfortunately, many of the letters’ readers, both nineteenth century and contemporary, have found them to be quite boring. You see, Fronto loved elaborate rhetorical hypotheticals, subjects that were somewhat ludicrous and absurd yet simply meant to allow a speaker to show off his rhetorical skills. For example, one surviving speech is called “In Praise of Smoke and Dust.” Another is called “In Praise of Negligence.”

It’s important to note that these letters date to the peak of what was known as the Second Sophistic, a time in which aristocratic Romans became particularly fascinated by the study of rhetoric and eloquence. As a result, the literature of this time period is often what we would consider to be rather over-the-top. (That’s why I love it so much; it’s just so weird).

Anyway, before these letters were found, people thought of Fronto as this Cicero-like man of stately grandeur. Angelo Mai’s discovery gave way to the shock that Fronto was, well, quite boring. Or so they assumed. The Fronto they imagined ought to be someone who wrote about important topics, not stupid things like dust and neglectfulness—never mind the historical context of the Second Sophistic, I guess. And “they” were wrong!

If you look at a portrait of poor old Fronto, you can see how it is that people want to portray him: as this elevated orator, far above the rest of us:

It seems fitting, though, that the bust’s actual visage does not survive: you can just see the outline of his countenance. Similarly, before Fronto’s letters were (re)discovered by Mai, all we had was, in essence, an outline or a sketch of Fronto. With the letters in hand, we have something more to go off of.

You can do the same thing for Marcus. Look at how reserved and stately he is here:

Now, let’s compare Portrait Fronto the distinguished orator and Portrait Marcus the Saintly Stoic with Epistolary Fronto and Epistolary Marcus, who were somewhat more vivacious. We have to be a little bit careful: letters, even genuine ones (and we are basically certain these letters are genuine and not spurious) are not always real life. Think of the myriad ways we curate ourselves on a day-to-day basis, the way we put on personas for others and then code-switch depending on the situation. But, nevertheless, these letters do give a more complete picture than the portraits do alone.

One of my favorite letters in the collection that my article discusses is 1.3 (from Marcus to Fronto) and its reply 1.4 (from Fronto back to Marcus).

In this letter, Fronto is apparently unwell, as he very frequently was: he seems to have suffered from a number of chronic illnesses, including chronic pain and chronic gut issues (ah, the ancients—they’re just like us). Marcus laments that he is not there to come help Fronto during one of his flare-ups (1.2.1):

Quid ego ista mea fortuna satis dixerim vel quo modo istam necessitatem meam durissimam condigne incusavero, quae me istic ita animo anxio tantaque sollicitudine praepedito alligatum attinet neque me sinit ad meum Frontonem, ad meam pulcherrimam animam confestim percurrere, praesertim in huiusmodi eius valetudine propius videre, manus tenere, ipsum denique illum pedem, quantum sine incommode fieri possit, adtrectare sensim, in balneo fovere, ingredienti manum subicere?

What would I say sufficiently, with that fortune of mine being what it is, or in what way would I rightfully find fault with that hardest necessity of mine, which holds me here in this way, bound, with my mind anxious and having been shackled with so great a worry, and does not allow me to immediately hurry to my Fronto, to my most beautiful soul, to go see him up close when he’s so sick, to hold his hands, and finally to gently handle that foot of his, as much as I can without hurting him, to foment it in the bath, to prop my hand under him as he is walking along?

Let me tell you, the Victorians were scandalized by this kind of effusive emoting from their Stoic hero. I leave it up to you how you want to interpret this kind of thing—keep in mind Marcus was probably 18 years old at this point, and we know teens love a melodrama moment. What I DO want to emphasize is how important friendship was to the Romans, even future emperors. While the Philosopher-Emperor Marcus we see riding on the horse above seems to be above such human things, the “real” Marcus was not just a deep thinker but also a deep feeler who cared a lot about his friends.

Fronto writes back in the next letter, 1.31 Instead of writing a normal letter, he decided to teach Marcus a thing or two about speechwriting, and composed his letter as a rhetorical praise of “love that doesn’t have a reason,” basically a showpiece of his eloquence and just the kind of thing a Second Sophistic rhetorician would want to compose to show off how good he is at orating (if that’s even a word). The opening is full of language reminiscent both of philosophy and poetry. In the first part of his encomium-in-miniature, he lays out his argument (1.3.5):

Tu, Caesar, Frontonem istum tuum sine fine amas, vix ut tibi homini facundissimo verba sufficiant ad expromendum amorem tuum et benivolentiam declarandum. Quid, oro te, fortunatius, quid me uno beatius esse potest, ad quem tu tam fraglantes litteras mittis? Quin etiam, quod est amatorum proprium, currere ad me vis et volare…At ego nihil quidem malo quam amoris erga me tui nullam extare rationem. Nec omnino mihi amor videtur qui ratione oritur et iustis certisque de causis copulatur. Amorem ego illum intellego fortuitum et liberum et nullis causis servientem, inpetu potius quam ratione conceptum, qui non officiis ut lignis apparatis, sed sponte ortis vaporibus caleat. Baiarum ego calidos specus malo quam istas fornaculas balnearum, in quibus ignis cum sumptu atque fumo accenditur brevique restinguitur. At illi ingenui vapores puri perpetuique sunt, grati partier et gratuiti.

Caesar, you love that Fronto of yours without end, with the result that words are scarcely sufficient for you, a most eloquent person, to display your love and declare your kindness. What, I ask you, is able to be more fortunate than me, what is able to be more blessed, to whom you send such blazing letters? But you even wish to hurry and to fly to me, that wish which belongs to lovers…But, indeed, I prefer that there be no reason of your love for me. Nor does love at all seem to me to be something which arises from reason, and which is joined from legitimate and certain causes. I understand love to be fortuitous and free and a slave to no causes, having been conceived by impulse rather than reason, a thing which grows hot not by duties that have been piled up, like pieces of firewood, but by vapors that have arisen of their own will. I prefer those hot caves of Baiae rather than those furnaces of the baths, in which the fire is kindled with expense and fume and is soon extinguished. But those natural vapors are pure and perpetual, both charming and freely given.

So, it’s clear that sculpted portraits of the great legends of the past only tell half the story. But so do letters: removed from their original context and composed at a very specific point in time, we can recontextualize and decontextualize them at will. It can be somewhat simple to understand the perspective of a formal state portrait of an emperor or famous politician: they connote power. How about literature, though? Especially personal writing between two friends, not really intended to be read by anybody else. Do you look at Marcus and Fronto differently having read the letters? I do.

This is basically the point of my article; when you read all these highly rhetorical and “flowery” letters all together, it seems like Fronto and Marcus were living out a perpetual bromance. Up to you to interpret as you will! I personally like the idea of a Marcus who was more fun than the Meditations would lead you to believe. And Fronto seems like a real hoot, able to spin some BS about anything and everything and call it a lesson in rhetoric.

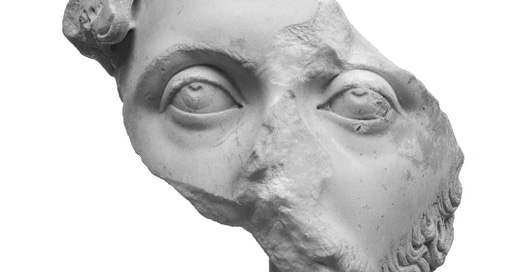

Of all the images I’ve seen of Marcus, I think I like this one from the Getty collection the best:

Fragmentary, just like the life writing we have of Marcus himself, yet somehow complete: the eyes are the window to the soul, and we get a look into Marcus’ intense, deeply thoughtful gaze. To me, the emotional nature of his early letters only enhances my appreciation of his Stoic philosophy: to master his emotions and gain inner tranquility, one must experience, accept, and appreciate the full range of human feelings.

Anyway, portraits are often inaccurate, as we know. Fronto tells us so, too. In many public spaces, Fronto writes, he frequently saw statues of Marcus in various public places that had been sculpted and painted in a “very unsophisticated style” (lutea…Minerva, letter 4.12.6). All the same, Fronto still likes them anyway: Cum interim numquam tua imago tam dissimilis ad oculos meos in itinere accidit, ut non ex ore meo excusserit rictum osculi et somn<i>um (“But when your image, no matter how unlike you, catches my eye on my way, this never happens without jolting from my mouth the gape and dream of a kiss,” 4.12.6).2

(I might have to write an article about this letter, too…it didn’t make it into the first one. It’s just too good, though.)

To me, this seems to mirror our own experience of learning more about historical figures: we like portrayal of them that are good and bad alike, polished and unpolished, fact and fiction, because they all add up to an image of the person in question that is greater than the sum of its parts. The formal portrait of antiquity hides the many facets of a person, presenting one cohesive image; the letter gives us so many more angles, and they may or may not be any more the result of careful sculpting and polishing. The mystery is what intrigues us.

As Glenn Most remarks (2009: 18):

Real wholes are ephemeral and start falling apart even before they are finished. Their fragments last much longer and yet they too are subject to decay and corruption. The only thing that is truly immortal is the lost whole that we reconstruct on the basis of fragments, that never existed in reality, and that therefore can never perish.

The fragments we saw today, and so many others, work together to create such imperishable portraits of Marcus and Fronto. And each of us as reader or viewer gets to be the creative lead on that construction of those portraits.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter!

If you enjoyed this week’s newsletter, read my forthcoming article sometime this year when it comes out :) or, better yet, read their letters yourself!

Take care until next time.

MKA

It’s important to note that the person who arranged these letters in a collection often did not put letters in chronological pairs, but would usually put together letters that COULD have replied to one another, but actually did not: they just have similar themes. So this might not be the “true” reply to letter 1.2, but it was a letter that Fronto wrote to Marcus around the same time period. DM me if you’re confused, it’s ok.

This section is unclear from a textual standpoint, and here it is more comprehensible if one employs the reading rictum osculi et somn<i>um as opposed to van den Hout’s iactum osculi et savium, which he describes as a “desperate effort” (van den Hout 1999: 185, ad loc.). Here, I follow the text of Haines’ Loeb edition and the translation of Amy Richlin (2006).