This post is part of an ongoing series on the heroic and antiheroic figures of Greco-Roman myth. Read Part 1 here! Eventually, this series will cover others of the many and numerous characters from mythology who are morally grey, as opposed to wholly noble and good. This week’s newsletter is a much-needed sequel to Part 1 on the Trojan War hero Achilles.

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

In Part 1 of this series, I talked a little bit about the nuanced portrayals of Greek heroes in both mythology and art. We left off with a very charming image of Achilles not simply as a conquering hero: instead, he is sometimes presented variously as a bloodthirsty necrophiliac, a vengeful shade, or even a trafficker of corpses.

For today’s virtual tour, let’s do a deeper dive into scenes of the infamous “ransom of Hector” scene. This is the mythological vignette in which Achilles makes King Priam of Troy buy back his son’s dead body after Achilles has tried to mutilate it beyond recognition, or at least makes Priam grovel a bit for it.

One of my favorite pieces at the Getty Villa is this second century sarcophagus with scenes from the life of Achilles. On the front is Achilles dragging Hector’s body around the walls of Troy, which is kind of the setup to the “ransom” scene itself:

As an aside, you might be wondering why someone would want such a gruesome scene of attempted corpse defilement on the tomb that would one day hold their own corpse. I think the answer must lie with Hector himself: as Homer’s tale goes, the gods did not allow Hector’s body to be torn apart. Even after this mistreatment, Hector was able to have a proper burial, and he enjoyed an eternal legacy of heroic glory and duty to one’s city. On the flip side, maybe the owners of this sarcophagus were simply drawn to Achilles’ bold statement of victory over his enemies. Both interpretations are valid! Or any others.

The infamous “ransom of Hector” scene

The artistic and literary portrayals of the ransom of Hector can be placed broadly in two categories: those in which the corpse is present, and those in which it is not. This seemingly minor detail has a substantial impact on the characterization of the figures in the scene. It is helpful to start with the Iliad, in which the body is absent during the proposal of the ransom itself. This event takes place in book 24, the last of the epic. Once Priam arrives before Achilles, he makes an emotional plea to his son’s killer (Iliad 24.505-508, translated by yours truly):

ἀλλ᾽αἰδεῖο θεούς, Ἀχιλλεῦ, αὐτον τ᾽ἐλέησον,

μνησάμενος σοῦ πατρός· ἐγὼ δ᾽ ἐλεεινότερός περ,

ἔτλην δ᾽ οἷ᾽ οὔ πώ τις ἐπιχθόνιος βροτὸς ἄλλος,

ἀνδρὸς παιδοφόνοιο ποτὶ στόμα χεῖρ᾽ ὀρέγεσθαι.

But revere the gods, Achilles, and pity me myself, having remembered your own father; but I am much more pitiable, and I endured such a thing that no other mortal on earth ever endured: to stretch to my mouth the hand of the man who killed my son.

The solemn nature of this scene did not preclude it from more lighthearted interpretations. There was often a certain focus on the unheroic or even “sacrilegious” in Greek art that can be more surprising to a modern audience than it would have been to an archaic Greek one.

However, one vase particularly stands out: a black-figure amphora in Boston, which is attributed to the Painter of Munich 1379:

This vessel may depict Hector’s ransom; here, the corpse is absent, which, as A. Brownlee (1989: 4) remarks, “actually makes the vase seem closer to the story as it is told in Iliad 24 than as it is depicted on the other vases,” since most scenes do not feature Hector’s body on display while Priam and Achilles have their moment.

This vessel also has some more unusual features: one of the mules is ithyphallic (which means—well, just look it up if you can’t guess) and the cart carries amphorae full of wine. These features have led Brownlee to conjecture that this scene is a parody of the ransom scene. Comedy was indeed a part of the City Dionysia, which was a festival in honor of the wine/madness/theater god Dionysus. In this context, humorous reenactments may have been part of the festivals long before comedy’s official establishment as part of the festival in 440s BCE.

Of course, Brownlee’s theory has not been met with unqualified approval; for example, Alexandre Mitchell (2009: 69) notes that “the elements of parody are sparse.” What I want to emphasize is that, in vase paintings like this, the line between the heroic and the unheroic is not so firm.

Brownlee notes that there were possibly other parodic ransoms of Hector circulating in antiquity, such as a now-lost comedy called the Mule-Cart, written by Philonides, an older contemporary of Aristophanes.

There’s often quite a bit of emphasis on the fact that Priam kisses Achilles’ hand, a reverent gesture that shows how far Priam is willing to humble himself to get Hector’s body back from the enemy.

A Roman silver cup from the first century BC provides an especially striking illustration:

Priam kisses Achilles’ hand, and the sharp lines of the decoration leave an equally strong impression on the viewer. The cup seems to respond to Iliad 24.477-479:

τοὺς δ᾽ἔλαθ᾽εἰσελθὼν Πρίαμος μέγας, ἀγχι δ᾽ἄρα στὰς

χερσὶν Ἀχιλλῆος λάβε γούνατα καὶ κύσε χεῖρας

δεινὰς ἀνδροφόνους, αἵ οἱ πολέας κτάνον υἷας.

Great Priam escaped the notice of [the Greeks] as he was going in, and, standing nearby, he took the knees of Achilles with his hands, and kissed Achilles’ hands, terrible and man-slaying, which slew many of his sons.

There may also be something going on with the fact that the Trojans were often characterized as “other” than the Greeks, even though they seemed to be able to communicate in the same language, they overtly worship the same gods, and otherwise seem to have similar customs.

In a number of red-figure vases, Priam wears Eastern-style clothing right down to his shoes. An example of this is the Brygos skyphos:

Miller (1995: 459) has argued that

[Priam] is iconographically most ‘specific’ in the ransom of Hektor’s body…from the later sixth century, several painters elaborate the Ransom scene to include one or more gift-bearers to Achilles. Commentators note that the image bears striking similarity to Persian imperial iconography, in which depictions of processions of gift-bearers to the Great King play an important role. It is even suggested that the very multiplication of numbers of attendants elevates Priam to the status of Great King.

With this in mind, it seems possible that scenes of the ransom of Hector scene reflect greater concerns regarding the polarity between Greek and foreigner, self and other; when Achilles and Priam share a moment of lament, they share a part of themselves with the other; Priam stands in for Achilles’ absent father, while Achilles stands in for Priam’s dead son. The scene urges the viewer to similarly reinforce this return to self, which, in this conceptual framework, takes place exclusively via compassion, not enmity.

Still, sometimes the compassion part is minimized or even erased. In the now-lost play of Aeschylus called The Phrygians (another word for “Trojans”), Achilles seems to have insisted that Priam pay Hector’s bodyweight in gold. We know this because of the work of scholiasts, who are people from antiquity who wrote commentaries on literature. The scholiasts note the contrast: on the one hand, the Iliadic Achilles is speaking out of exaggeration (ὑπερβολικῶς), but in Aeschylus’ play there really was a weighing out in gold. In the original production, the shock value of this demand may have been further heightened by the fact that the gold was counted out on stage, before the very eyes of the viewers.

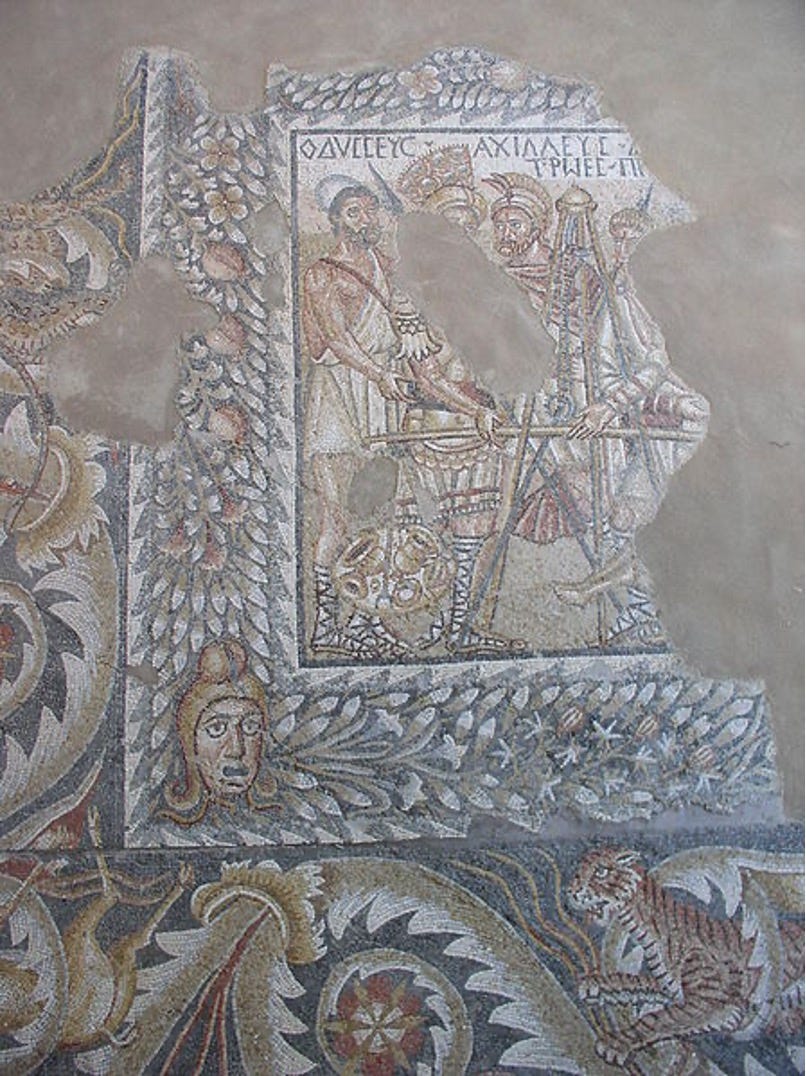

Artists continued to engage with the Phrygians several hundred years later, during the Roman Imperial period. In the Caddeddi villa, a fourth-century CE house not far from the Tellaro river in southeastern Sicily, there are remains of what was once a larger floor mosaic.

The largest fragment depicts the ransom of Hector, which provides evidence of visual intertextuality with Aeschylus’ Phrygians in the late antique period. The iconic scene has some remarkable features: Achilles wears peacock feathers in his hair, while Priam prepares to pay Achilles for his son, as gold vessels are being weighed out.

Peacocks were the ultimate status symbol; they were linked with Hera and even appeared on Samian coinage at various points, commanding respect due to their beauty and luxury (Pollard 1997: 147). They were also seen as symbols of “eastern” decadence and elitism, and they might make Achilles into a heavily-stereotyped “tyrant of the east” figure.

So, what’s the “point” of all this? It’s not like, on the whole, we’re supposed to hate Achilles or somehow take away his hero-status. I think the lesson must be about the fine line between justice and injustice, and the situations in which transgressions against social norms are “acceptable” (i.e., in the case of heroes like Achilles, who get special treatment) and unacceptable (i.e., in everyday life). This is one of the purposes of literature and art: to allow us to explore the extremes of the human experience in a way that is also somehow removed from our actual lives.

To that end, there’s an interesting fragment left from The Phrygians, even though most of the play does not survive (Phrygians fr. 266; translation by A. Sommerstein):

καὶ τοὺς θανόντας εἰ θέλεις εὐεργετεῖν

εἴτ᾽ οὖν κακοθργεῖν, ἀμφιδεξίως ἐχει

< >

καὶ μήτε χαίρειν μήτε λυπεῖσθαι βροτούς.

ἡμῶν γε μέντοι νέμεσίς ἐσθ᾽ ὑπερτέρα,

καὶ τοῦ θανόντος ἡ Δίκη πράσσει κότον

And if you want to do good to the dead, or again to do them harm, it makes no difference, for <the lot of> mortals <when they die is to have no sensation> and feel neither pleasure nor pain. Our indignation, on the other hand, is more powerful, and Justice exacts the penalty for the wrath of the dead.

As ever with tragedies, the meaning is somewhat obscure. I take it to mean that the dead, like Hector, don’t care about things like being dragged around the walls of Troy—instead, it is the living who feel indignation and rage on their behalf, so Justice comes anyway. At the same time, the “wrath of the dead” sounds like the dead do experience wrathful feelings (much like Achilles’ own infamous wrath). The Ancient Greek is a little bit ambiguous; I think it could also mean anger on behalf of the dead. Once again, the impact of Achilles’ actions are nuanced and cannot be completely explained or articulated: it is up to each reader or viewer to interpret.

Finally, I wanted to end with a take on Achilles that is less vengeful and unpleasant: there is a mythological tradition of Achilles actually being a doctor or healer figure as well, and in addition he was well-known for his love of his dear friend, Patroclus. This is one of my favorite images from antiquity, which shoes Achilles bandaging up his friend after he has been injured in battle:

Even though this particular newsletter focuses on the more negative sides of Achilles’ personality, he was still a beloved hero revered for his valor, courage, and strength.

Thank you for reading this week’s edition of Reading Art!

I hope you enjoyed this week’s newsletter. Which hero should I write about for the next installment? I’m thinking maybe Jason and the Argonauts, but we’ll see. Take care until next time.

MKA

Some resources to help victims of the Los Angeles wildfires: