Morally Grey Heroes of Ancient Greece, Part 1

When it comes to Ancient Greek heroes and villains, the two are sometimes one and the same

CW: this week’s newsletter includes discussion of suicide, dead bodies, murder, and other deviant/antisocial behaviors

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

Happy New Year! I hope your 2025 has been off to a good start. Are you a goal-setter? Or do you prefer to take the year as it comes?

Some of my goals for 2025:

Finish my PhD(!)

Read more nonfiction for fun, not just for work/dissertation

Visit a new exhibition or gallery every month, or when possible

And, of course, I want to keep publishing a virtual and very eclectic gallery tour every week :) If there’s anything you’d like to see from Reading Art in the new year, leave me a note in the comments.

Onto our topic for today: Heroes & Villains in Ancient Greece. New Year’s resolution time got me thinking about the best version of humanity and the ways in which we as a society idealize certain people. Every culture has its heroes. You might think of a famous historical figure like Abraham Lincoln or Martin Luther King, a pop culture icon like Madonna or Taylor Swift, or even athletic heroes like Tom Brady or LeBron James. Heroes are also local and tied to a specific community: firefighters, paramedics, or even beloved family members. Heroes become larger than life, symbolizing the best of us as a collective society.

The word “hero” meant all of this and more in Ancient Greece. There were, however, some significant cultural differences. First, heroes were not worshipped simply in a figurative sense, but also in a literal one. In today’s world, heroes are expected to be virtuous, to unfailingly live up to our expectations of them. Otherwise, how could they rightly be classified as heroes?

But the Greeks had a different set of values in mind when it came to hero worship. Many of the characters known as heroes from classical mythology are also deeply flawed: they feel jealousy and wrath, they commit sacrilege, they engage in various brutal and cruel actions. In today’s virtual gallery tour, we’ll take a closer look at the nuanced portrayals of heroes in myth and art as well as their greater cultural significance. This is the first of a series that will highlight a different Greek hero, and we’ll start with one of the most famous of them all: Achilles.

Hero cults in the Ancient Mediterranean

First, some background on the meaning of “hero” in Greece.

The very category of “hero” (ἥρως in Ancient Greek) is a sort of nebulous one that has sparked extensive scholarly discussion for over a hundred years. Some (e.g. Bremmer 2006) have argued that there is not sufficient literary or archaeological evidence to talk about hero cults in a strict sense. The category of “god” is much more obvious, as it refers to a divinity. Ritual worship of the deceased and/or of ancestors is also somewhat easier to conceptualize. But heroes are kind of in a “neither here nor there” category. If you’ve read any ancient literature, you know about Achilles, Hercules, Odysseus, and so on. Many of them are either the children of the gods or have divine lineage in some sense. In some cases, as with Hercules, they become gods upon their death. As it stands, however, heroes are not strictly divine, but neither are they strictly human. I mentioned before that you probably have heard of at least one Greek hero—there’s more popular ones, like Odysseus or Oedipus, medium-popular ones like Jason or Perseus, and more obscure ones you’ve probably never heard of, like Erechtheus.

This is where the idea of the hero cult comes in. People would put up monuments to specific heroes, oftentimes because they believed that the hero in question had either founded or come into significant contact with their city. These appear not only in Greece but also throughout the Mediterranean world. People would venerate them with sacrifices and dedications, and there were sometimes local rituals or holidays to commemorate the hero’s life.

In many cases, the monument in question would be a tomb for the hero, whether in a symbolic sense or because the community in question believed that the hero had really been buried there. It has been theorized that this was, in part, due to the widespread influence of Homer and other epic poets who made various heroes so popular in their works.

So, to summarize up to this point: the heroes were better than regular humans, because they had achieved great things in their mortal lives, but they were still, well, mortal, and therefore unlike the gods, who were characterized by their deathlessness. Their behavior could be praiseworthy or reprehensible, but people worshipped them all the same.

It is this darker side of heroism that we’ll be focusing on today. As I mentioned above, today we’ll look at the hero Achilles as a case study.

Achilles: a flawed hero in the Trojan War and beyond

First, Achilles. Homer’s epic poem The Iliad tells primarily of his exploits during the Trojan War, the conflict between the nation-states of Greece and the city of Troy that arose when a Greek queen, Helen, either decided to go or was forcibly taken to Troy (accounts vary) to marry Paris, a Trojan prince. Achilles appears in dozens of other myths as well, both those about the Trojan War and those that are not.

Achilles famously had a choice to make when it came to his destiny: he could live a long life in obscurity, or he could become famous and win glory (kleos) for himself but die in the Trojan War. A lover of glory, Achilles chose the latter.

The hero Achilles is best defined by his superlative status: according to the Iliad, he is the strongest, the swiftest, the most beautiful, and the “best of all the Greeks” (ὁ ἄριστος Ἁχαίων) but he is also the most violent, sometimes addressed with the vocative πάντων ἐκπαγλότατ᾽ ἀνδρῶν (“most violent of all men”).

He was said to have a fierce and even savage nature: there’s a reason why the first lines of the Iliad go something like “sing to me, Muse, of the dread wrath of Achilles, Peleus’ son, harsh and intractable, which sent countless souls of the Greeks down to Hades.” Achilles as a heroic figure acts as both a familiar hero who ties together different groups with his universal appeal, but he is also a foil to the collective values of the community, as his behavior often defies human norms and customs.

Yes, Achilles’ efforts ended up going a long way to winning the Trojan War for the Greeks. But he didn’t always behave in a way that either humans or the gods condoned. For example, after killing his archenemy Hector, who had in turn killed Achilles’ best friend and possible lover Patroclus, Achilles didn’t follow cultural protocols around treating corpses with dignity, even those of enemies. As the story goes, Achilles was so angry at Hector’s slaying of Patroclus that he tied Hector’s body to a chariot and continuously rode the chariot around, keeping Hector from a proper burial with his family.

Now, the gods prevented anything from happening to Hector’s corpse, because Hector was so pious and good that Achilles’ actions pained them (see Iliad 24.20, for example, when Apollo covers Hector’s body with his aegis to prevent Achilles from harming it while he drags the corpse behind his chariot). But it took a personal mandate from Zeus for Achilles to finally return Hector’s corpse to his family.

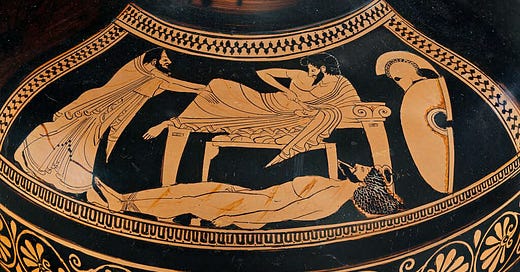

In the scene on the vessel above, Achilles begrudgingly agrees to return Hector to his father, King Priam, but only if Priam will pay a hefty ransom—and if Priam comes to beg in person, as you see above.

This is quite an interesting depiction of the scene, as Achilles reclines on a couch as though he’s at a Greek dinner party. Legend had it that Achilles’ thirst for blood was so great he almost sank his teeth into Hector’s corpse like an animal, and I wonder if the artist’s choice of Achilles’ pose has anything to do with that characterization. As a heroic figure, Achilles has a range of experiences that oscillate between superhuman valor and non- or even sub-human urges.

Artists and authors alike grappled with how to best portray Achilles and Hector. Achilles is the conquering hero, but his behavior in war was far from praiseworthy; Hector lost, but seems in many ways to have been Achilles’ moral superior. In a lesser-known epic from antiquity written by 3rd-century BCE poet Lycophron, called the Alexandra, the poet discusses the aftermath of some of the events of the Trojan War, focusing on the Trojan princess Cassandra.

At lines 1189-1213, Cassandra describes the establishment of a hero cult for Hector following the transferal of his bones to Thebes, where Hector will be a “defender against the arrows of the plague” (ἀρωγὸς λοιμικῶν τοξευμάτων, 1205). Thebes is an interesting location for Hector’s hero cult; as the birthplace of Dionysus, god of theater, the city is also the birthplace of tragedy. Hector, a newfound deity of healing, brings restoration and peace to a city whose mythological past is as fraught with pain and suffering as his own.

This isn’t to say that Hector became a major divinity in the Mediterranean world or anything like that, but it is interesting that there was some interest in giving him such an illustrious afterlife.

Indeed, Achilles may have technically been the greater hero, but he was also the king of deviant and antisocial behavior. Here he is on another vessel slaying the Amazon heroine Penthesilea, who came to try and help the Trojans win the war (unsuccessfully, obviously):

As the story goes, Penthesilea put up a good fight, but she was no match for Achilles. Just after Achilles killed her, however, he allegedly fell in love with her, but was too late—she couldn’t be saved. There are some fairly disturbing myths about Achilles’ necrophilia problem that I’ll just skip right over for the good of us all. Still, the portrayal on this vessel has Achilles stabbing poor Pen through the heart, which maybe alludes to his unluckiness in love. The eye contact in this depiction is also more intense than many others. Achilles’ eye looks huge, even through his armor, and we can see Penthesilea gazing up at him. If they weren’t holding spears, they could almost be dancing. P. was a heroine in her own right, and her death was treated as a tragedy by the Greeks.

The myths about Achilles’ ruthless nature continued on even after he died, killed at the hands of Paris in a divinely-orchestrated downfall. According to Philostratus and others, Achilles continued to live on in a state of semi-immortality on Leuke, an island in the Black Sea, where he lived with Helen. In Philostratus’ account, the vengeful spirit of Achilles continued to demand the blood of Trojan maidens even long after the conflict had resolved.

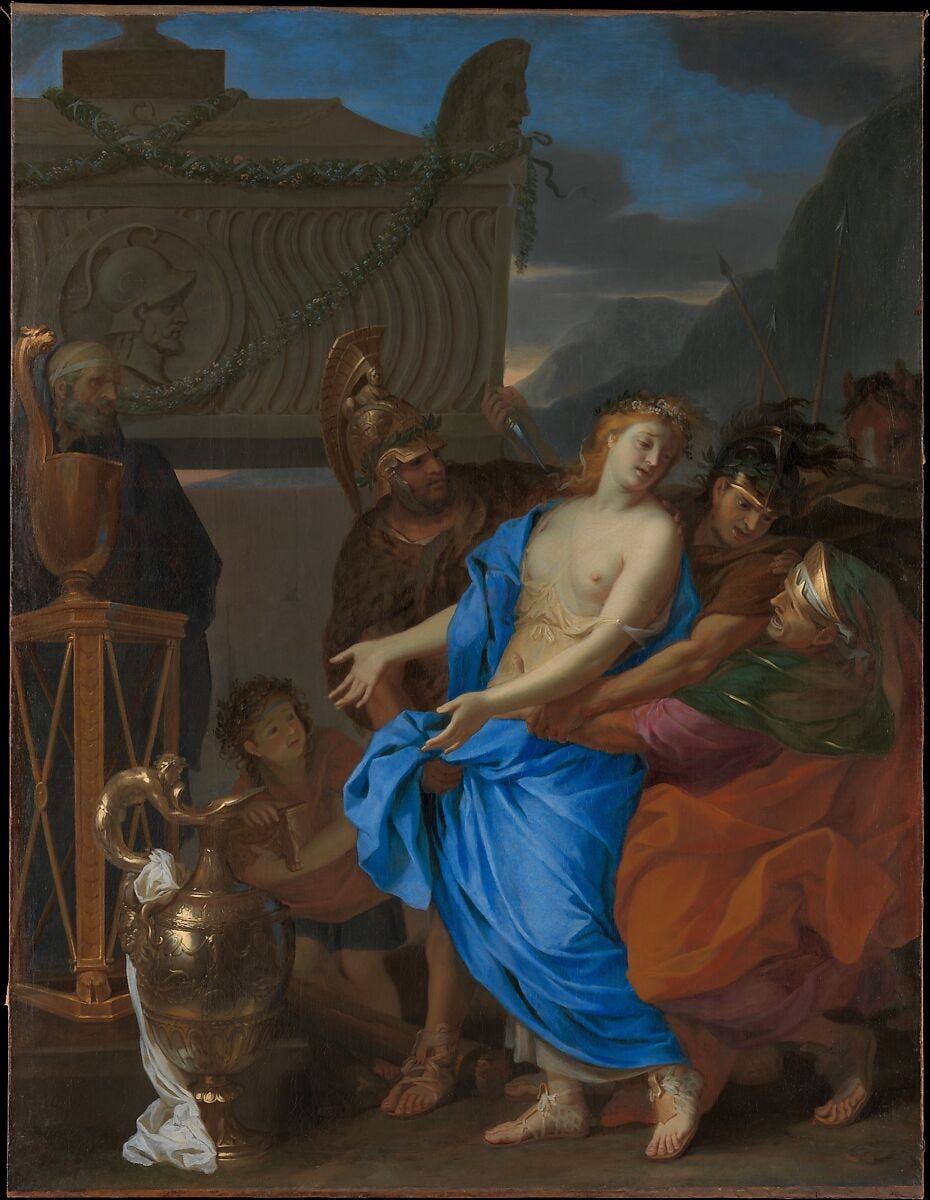

More famous is the story of Achilles’ ghost and Polyxena, a Trojan princess who was captured along with her relatively few remaining family members after the Greek victory. Apparently, Achilles had been planning to marry Polyxena while he was alive to try and unite the Greeks and Trojans, but the deal fell through. His apparent love for her, however, didn’t stop after death—and he wanted her to join him as quickly as possible. Resultantly, the wretched Polyxena was sacrificed in front of Achilles’ tomb:

There are many ancient depictions of this scene, but I love this seventeenth-century rendition by Le Brun. You can see the elaborate tomb for Achilles in the background, and the golden vessel in the foreground that probably held Achilles’ burned remains, to be interred within the tomb. Polyxena’s mother, Queen Hecuba of Troy, clings to her daughter as she is led away, but it’s no use.

According to Euripides, the Greek tragedian, in the end Polyxena actually voluntarily went off to be slaughtered so that she could appease Achilles’ still-wrathful spirit. Her open-armed gesture and closed eyes seem to indicate that she embraces death willingly, and the bright blue of her garment maybe symbolizes calm and acceptance, as opposed to the emotive oranges and reds of Hecuba’s clothing. It’s actually a bit difficult to see the small dagger aimed right for Polyxena’s heart—maybe another gesture at Achilles’ doomed and unfortunate—and the emphasis is placed on Polyxena’s expression. The stormy sky in the background points to Achilles’ anger, but maybe also that his demand from beyond the grave is an unrighteous one that the gods do not approve of, as they disapproved of his actions with Hector.

And yet, despite all of these things, the Greeks still worshipped and loved Achilles. Alexander the Great and even some Roman Emperors aspired to be like him, using the Trojan War narratives as examples of bravery. If Achilles’ more unsavory inclinations are brought up, they seem to be forgiven in light of his overall glorious life, even if these behaviors are definitely not presented in a positive light. Reading Greek mythology involves a lot of cognitive dissonance! But it’s ultimately quite interesting to see what resonated with a Greek audience and what they were able to overlook.

To conclude, I want to draw your attention to this abstract work by Barnett Newman, titled Achilles:

Newman liked biblical/mythological titles for his works, and I’m particularly drawn to Achilles because of its bright red color. Achilles is, in an abstract sense, deconstructed right down to his most essential quality: rage (Greek mēnis), a fearsome wrath that defies all reason and control. The particulars of Achilles’ life are very detailed, but it is this one fundamental emotion that ties together the vast collection of stories about him, the driving force behind his quest for glory.

Thank you for reading this week’s edition of Reading Art!

So there you have it: Achilles was both very brave and strong and also quite disturbed in many ways. Greek myth is nothing if not colorful! There are numerous other examples of the less-than-righteous behavior of Greek cultural heroes (or maybe we should call them antiheroes). I was going to discuss more of them in this week’s newsletter, but there was just so much to say on Achilles that I wanted to save the others for another time. In fact, there is much, much more to say even on Achilles. I’m going to make this into a series on the many flaws of A. and other Greek heroes—stay tuned for more later.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts. Take care until next time.

MKA