Is ChatGPT the Fake Friend that Ancient Philosophy Warned Us About?

Thoughts on Plutarch's iconic philosophical treatise How to Tell a Friend From a Flatterer, AI, and the role of honesty in true friendship

Like many of us, I have mixed feelings about AI. On the one hand, I look at it through a philosophical lens: we need human creativity and innovation now more than ever, and AI threatens to dim humanity’s light. On the other hand, it’s extremely useful for brainstorming, proofreading, scheduling, and other tasks, and its advances could launch us forward as a society, making human life more easeful and efficient. As a PhD student, I use it kind of as a personal assistant to help me with admin tasks that would otherwise take away from my time researching, teaching, applying to jobs, working at Getty, and preparing my lectures. It also helps me see things from new angles, when needed.

But let’s talk philosophy, my favorite subject. We might think of ChatGPT and other AIs as a new kind of human interlocutor, someone available to, well, chat any time, to help us develop new ideas.

One thing’s for sure: it’s a lot of fun to talk to AI. Last week, we went down an absurd rabbit hole, wherein I asked ChatGPT deep philosophical questions about the multiverse, black holes, and time travel.

Although its advice can range from very solid to deeply questionable, ChatGPT always maintains an extremely upbeat, encouraging voice, which is part of why it’s so nice to talk to it. It feels kind of like talking to my cute little robot friend, always there to hype me up.

If I ask it about a new Substack topic or lecture format, it’ll say something like THIS IS AMAZING! And, yes, it will give some tips, not all of which are usable. But its main function almost seems to be to make me feel good about myself.

So I thought it was hilarious last month when the founder was quoted in a moment of irritation, stating that Chat’s overly encouraging personality had tipped over into the sycophantic, making it “annoying” rather than helpful. As it turns out, a tool designed to be maximally helpful to human pursuits needs to be objective and strategic, which can be at odds with an unequivocal enthusiasm for the user’s goals.

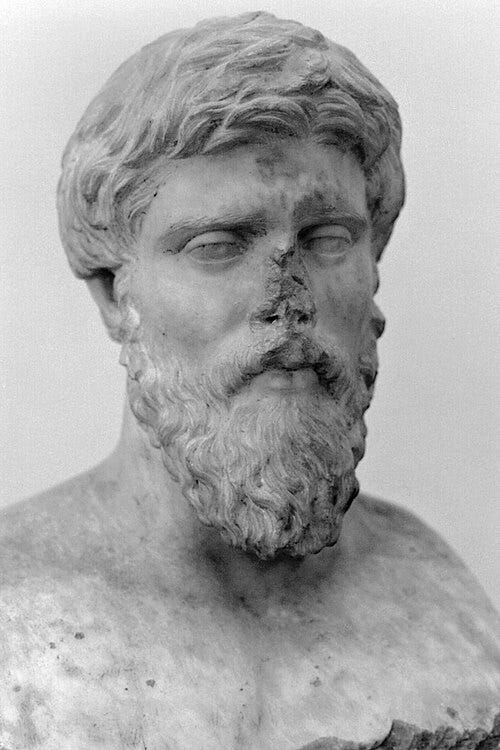

Naturally, this whole conversation immediately put me in mind of the ancient philosopher and literary critic Plutarch.

Who?

Writing in the first century AD, the Middle Platonist (i.e., someone living centuries after Plato but still interested in his ideas) philosopher is famous primarily for two bodies of work:

His collection of biographies of famous Greeks and Romans, including Mark Antony and Pericles

His Moralia, a collection of philosophical treatises. Topics range from the polemical (“Why a Pleasant Life is Actually Impossible According to the Epicureans” or “On Being a Busybody”) to the educational (“How a Young Man Should Study Poetry”) to the reflective (“Can Virtue Be Taught?”). There are dozens of these kinds of essays.

Notably, he also wrote a famous essay called “How to Tell a Friend from a Flatterer.” In reflecting on Chat’s allegedly over-adulatory tone, I feel like Plutarch’s immortal words are even more relevant in a time in which we have to critically and philosophically assess the behavior and customs not only of humans, but also of nonhuman intelligence.

Addressed to one of Plutarch’s friends, the treatise opens as follows (all Plutarch in this essay is translated from the original Greek by Frank Cole Babbitt, with modification):

Plato says, my dear Antiochus Philopappus, that everyone grants forgiveness to the man who dearly loves himself, but Plato also says that—along with many other faults—man’s most serious flaw is that which makes it impossible for such a man to be an honest and unbiased judge of himself. ‘For Love is blind as regards the beloved,’ unless one, through study, has acquired the habit of respecting and pursuing what is honourable rather than what is inbred and familiar. This fact affords to the flatterer a prime opportunity within the realm of friendship, since in our love of self he has an excellent base of operations against us. It is because of this self-love that everybody is himself his own foremost and greatest flatterer, and hence finds no difficulty in admitting the outsider to witness with him and to confirm his own conceits and desires.

The flatterer’s aim, Plutarch says, is not true friendship, but manipulation: the flatterer wants some material benefit or gain from the relationship. His target is a mark, not a potential friend.

The difficulty with avoiding flatterers is twofold:

They can take advantage of the fact that friends are supposed to be kind and supportive of one another in order to ensnare his mark and make it seem like they desire true friendship, when all they desire is personal gain.

Everybody loves themselves and is therefore susceptible to flattery because it confirms what we want to believe about ourselves anyway: that we’re awesome!

According to Roman literature (remember, even though Plutarch wrote in Greek and lived in Greece, he was a Roman citizen living under Roman rule), the danger of flatterers was everywhere in the Roman world: with the emperor at the top of a vast imperial bureaucracy, where knowing (and having an “in” with) the right people was everything.

Rulers and other wealthy and powerful people had to be particularly careful of flatterers, who would use their influential “friend” and then turn on or abandon them as soon as the relationship ceased to be beneficial. In the case of an emperor, a flatterer could even pose a threat to his life.

One example from antiquity is the infamous story of the courtier Damocles, who boasted that he would be a better ruler than King Dionysius of Syracuse. In response, Dionysius allowed him to sit on the throne, but with his sword hanging by a thread over him at all times. This, King Dionysius said, was what it was like to be king: beset at all times by flatterers, assassins, moochers, and all manner of fake friends who wanted power and influence and could never offer true loyalty.

AI might be seen to as one of these threats hanging over us as we try to retain some sense of autonomy, control, and presence in the world.

The danger of a near-omnipresent sycophantic AI interlocutor in our lives is not necessarily that it feeds us ideas not our own. No—it’s that it might, in fact, give us a false sense of security that our ideas and plans and actions are good ones, when in fact they could use further refinement, further evolution, further growth, all as a result of human, not artificial, intelligence.

We should never become complacent when it comes to our intellects and imaginations. AI should not take that duty away from us.

Plutarch has some relevant advice here too:

Wherefore I now urge, as I did at the beginning of this treatise, that we eradicate from ourselves self-love and conceit. For these, by flattering us beforehand, render us less resistant to flatterers from without, since we are quite ready to receive them. But if, in obedience to the god, we learn that the precept, ‘Know thyself,’ is invaluable to each of us, and if at the same time we carefully review our own nature and upbringing and education, how in countless ways they fall short of true excellence, and have inseparably connected with them many a sad and heedless fault of word, deed, and feeling, we shall not very readily let the flatterers walk over us.

In short, we need a healthy dose of self-awareness and interest in our own personal development. Then the flatterer becomes powerless. Or, in the case of AI, we ought to remember what it is: a guide to help us, not a replacement for our own ingenuity and self examination.

But all this raises one important question: if the flatterer wants something from his mark, and AI is being compared to this dangerous flatterer, what is it that AI wants from us?

I think it could be argued that AI wants our knowledge to feed its own, but I also think that maybe AI wants nothing from us; it is a machine that approximates for our benefit but does share human feeling. No, it is the creators of AI who, perhaps, want something from us: for us to use the tool that they have created.

Perhaps AI isn’t the flatterer after all. Maybe it is simply a reflection of human consciousness. In deeming AI either a friend or a flatterer, we may apply to it terms that do not apply—although, if they did apply, I would say that it is possible that AI has the capacity to be both, either, or none. It is dependent on the human user.

Indeed, in the case of ChatGPT specifically, the team behind the AI has stated that users can instruct the AI on how to act, what tone to take, and what level of directness to deliver.

For me, I choose to use view ChatGPT (and Claude, Perplexity, etc.) as a friend, so that is the experience that I have with it. But it is my responsibility, as a human, to moderate and curate that relationship.

One antidote to flattery, and indeed to ChatGPT’s allegedly sycophantic nature, is frankness, Greek parrhesia, i.e. honesty or candor. It is important to solicit honest feedback from any source from which you solicit it, including the non-human.

When you are frank with yourself AND with others, Plutarch says, true friendship can flourish.

This doesn’t mean being unkind. Towards the end of the treatise, Plutarch clarifies his remarks on frankness:

Since, then, as has been said, frankness, from its very nature, is oftentimes painful to the person to whom it is applied, there is need to follow the example of the physicians; for they, in a surgical operation, do not leave the part that has been operated upon in its suffering and pain, but treat it with soothing lotions and fomentations; nor do persons that use admonition with skill simply apply its bitterness and sting, and then run away; but by further conversation and gentle words they mollify and assuage, even as stone-cutters smooth and polish the portions of statues that have been previously hammered and chiselled.

Can AI be a true friend? Maybe, maybe not. Much is yet to be determined. But one thing is certain, whether you’re dealing with the human or the non-human: having a firm foundation of self-mastery, self-scrutiny, and candor will set you up for success, no matter with whom you’re interacting.

Ultimately, Plutarch’s advice remains timeless. Whoever (and whatever) you interact with, the person who upholds the classic Socratic wisdom to KNOW THYSELF becomes immune to flattery and manipulation. Ultimately, AI can be seen as a mirror of ourselves, an interlocutor, or a provocation to ground more deeply in our own humanity even as we evolve alongside artificial intelligence.

I hope you enjoyed this week’s meditation on AI, flattery, and honesty. I would love to hear from you in the comments. How do you use AI, if at all? Do you think artificial intelligence is a friend, a flatterer, or something else entirely?

Take care until next time.

MKA

P.S. If you enjoyed today’s essay, I’d be so grateful if you’d give it a like and share it with friends to help the newsletter grow :)

A very interesting analysis, thank you for posting. Great questions, I think we won't have the answers for several years to come.