The Sword of Damocles (and other tales of tyranny in antiquity)

Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown, and all that.

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

Given current events this week in the US, I thought it was a good time as any to make this week’s virtual gallery tour tyrant-themed. We can do as the ancients did and use the past as a way to both escape from and meditate on present circumstances.

In Ancient Greek, the word for “tyrant” is basically the same as it is in English (τύραννος, or tyrannos in its transliterated form). This term, however, did not necessarily have the same negative connotations as it did in English. Oftentimes it referred to someone who was the absolute ruler of his (yes, they were all men—if someone knows of a female tyrant in ancient Greece, lmk) nation (usually a polis, or city-state). For example, in Sophocles’ famous Oedipus the King, Oedipus is referred to as the “tyrant” of Thebes, even though people generally liked him and approved of his rule as king because he had defeated the evil Sphinx, a monster who was terrorizing the city. To defeat the Sphinx, you have to answer a riddle correctly or be killed, and Oedipus was the only one clever enough to figure out the solution.

That is, Oedipus was popular and well-liked until they figured out he had killed his father, the former king, married his mother, and caused the god Apollo to send down a plague that killed thousands of people because of his impious behavior. But even then, they didn’t call him a tyrant because of all that, just “accursed” and “hateful to the gods,” and everyone obviously felt very sad for poor Oedipus.

In other words, they didn’t call him a tyrant to rub it in, and they didn’t view him as a bad ruler—just one with a very unfortunate fate. Indeed, all of this had been fated to happen, and Oedipus is the archetypal example of someone who falls into the trap of a self-fulfilling prophecy: he tried his whole life to avoid his biological parents, and in so doing lays the foundation for the prophecy to be fulfilled.

I love this painting by French Symbolist painter Gustave Moreau (he was an influential artistic predecessor for Odilon Redon, whom we saw in last week’s post). Images of Oedipus and the Sphinx were fairly popular even in antiquity, and I always like the reminder that Oedipus’ whole life wasn’t lamentable: at heart, he was a hero. He just made a few mistakes along the way and ran afoul of fate.

In Moreau’s version, the Sphinx herself is rather small, which makes Oedipus look even more imposing as he looks down his nose at her: victory seems inevitable. And yet there are reminders of Oedipus’ looming future. On the right side of the scene is a ritual vessel with a snake coiled around it, which are symbols of prophesy and oracles, both associated with Apollo—the god responsible for predicting that Oedipus would kill his father and marry his mother.

Around Oedipus and the Sphinx are dead bodies, which could be interpreted as the many people who failed to answer the riddle correctly and were thus killed by the Sphinx. But I also like to imagine that the corpses also point to the fact that Oedipus is his father’s murderer, and that others will eventually die wretched deaths because of the plague caused by his actions and his inability to avoid the prophecy. The skeletons in Oedipus’ closet, so to speak, will come back to haunt him. Indeed, even in the hour of Oedipus’ victory, the sky is dark, further symbolizing the ultimate hollowness of his victory.

Starting in the fifth century, however, it became increasingly common for people to come to power in unconventional ways and also behave in increasingly unhinged and despotic ways, and the term began to take on more negative meanings.

Periander of Corinth

Next up on our list is Periander of Corinth (6th century BCE). Accounts of Periander are ambiguous; some say that he was cruel and ruthless, while others say that he was wise and just. Either way, Corinth seemed to prosper economically under his rule. Some sources list him as one of the Seven Sages of Ancient Greece, and state that he spent much of his time studying philosophy and composing didactic poetry on various intellectual topics. Some scholars suggest that there were two men named Periander, one the cruel tyrant and the other the wise man of Greece.

I suppose it’s possible, since Periander isn’t an uncommon name for an ancient Greek. At the same time, I would find it more intriguing if it was the same person. That would mean that Periander, cruel yet a lover of the arts and humanities, loved the idea of philosophy more than the practice of it, that he was unable to implement all his learning in his real life. At the same time, I wonder if this (probably fictitious) philosopher-despot assumed that the ends justified the means: that the short-term economic prosperity of Corinth meant that his methods were ok, even by philosophical standards.

Like many tyrants, Periander was allegedly very misogynistic, and was said to have kicked his wife down the stairs and killed her. According to Herodotus, he may also have, ahem, embraced necrophilia following the gruesome murder. Enough said on that, tbh. If Periander really was a Sage, then to me it didn’t mean much. Easier to think of them as two different people, but it certainly raises an important question: should a Sage be a good person, or just a lover of wisdom? I think they definitely should be righteous themselves in order to qualify.

Dionysius of Syracuse and the sword of Damocles

Other tyrants were more expressly interested in the dynamics of governing a state, but more or less failed to live up to the ideals of good kingship. Dionysius of Syracuse, for example, invited Plato to come and help him amend his ways, converting him from a cruel womanizer to a man of moral integrity. According to various ancient sources, Plato was successful for a time, but Dionysius’ true nature eventually gave out: Dio Chrysostom, writing in the Roman Imperial era, described Dionysius’ soul as a writing tablet that had been erased and written over so many times that it was impossible to try and make any more impressions on the page. In other words, even the great philosopher Plato couldn’t do anything with him. Once a cruel and ruthless tyrant, always a cruel and ruthless tyrant.

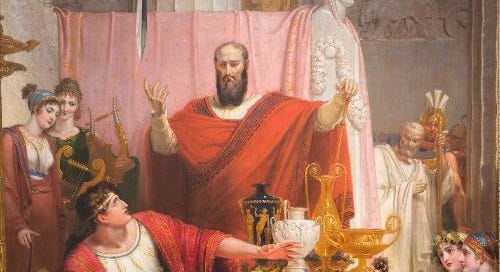

According to Cicero, however, even Dionysius’ worn-out soul may have had some flashes of insight. Allegedly, one day a man named Damocles, a courtier and aristocrat of Syracuse, boasted that he would be a better king than Dionysius. In response, Dionysius said that he would allow Damocles to experience what it was like to rule and then Damocles could decide how well he liked it. Dionysius made Damocles sit on the throne, but hung a sword above his head, attached to the ceiling only with a thin and fraying rope. This, said Dionysius, was what it was like to be the tyrant: there was always someone or something that could threaten your life and your power at a moment’s notice: slander, assassination attempts, coups, rumors, and any number of other hazards. Needless to say, Damocles was glad to step out of the spotlight.

I love the bright colors of Westall’s painting (the red robes are giving Spanish Inquisition) and the sword is surprisingly small and placed high above Damocles’ head. The grey of the metal almost fades into the grey of the wall, and there’s so much going on in the frame that you don’t really notice it too much. For some reason, whenever I imagine the scene, I picture a huge cleaver hanging right overhead. But you do notice the fact that Damocles is too distracted to pay any attention to the fawning servants or the lavish gold objects around him: all he can do is look up in fear at the sword. His reaction is greater than the object itself. Or is it? Sometimes it’s the smallest things that can be a tyrant’s downfall.

The ring of Polycrates

Polycrates, tyrant of Samos, illustrates this truth perfectly. In a story told by Herodotus and other authors, Polycrates was a king of Samos, an island nation. He had a formal guest-friendship relationship (xenia) with the King of Egypt, Amasis. This meant that the two of them had a sort of formalized agreement wherein they gave each other gifts, stayed over at each other’s houses if necessary, and had a kind of sociopolitical alliance going on, plus they were personal friends.

Amasis was a wise man, and one day he wrote to Polycrates that he was concerned that Polycrates had become too high and mighty. His city was flourishing, he was the uncontested sole ruler of Samos, and he was vastly wealthy. Amasis warned him that the gods can become envious of prosperous mortals and that he should do something quickly to make things more balanced. Amasis’ suggestion was that Polycrates choose his most prized possession and throw it away.

This idea seemed reasonable to Polycrates, so he chose what he believed to be his most prized possession (lol): a golden ring. He sailed out to sea and pitched it into the waves, believing it to now be gone. But a few days later, he received a visit from a local fisherman. The fisherman told him that he had caught the most beautiful fish he had ever seen and wanted to give it to Polycrates as a gift. This is the scene portrayed by seventeenth-century painter Salvator Rosa:

But when Polycrates ordered his cook to cut open the fish, they discovered something shocking: the ring was inside the fish, as it had apparently swallowed it down. When Amasis heard about this, he was terrified. To him, it was a bad omen that someone should be so prosperous that they even got back the things they tried to throw away. He promptly dissolved the guest-friendship bond and distanced himself from Polycrates.

I love Rosa’s rendition of the scene because he relocates it from inside Polycrates’ palace to the outdoors. Their seventeenth-century clothing brings the story to Rosa’s present day, making more of a universalizing statement about fortune, arrogance, and tyranny. I also love how you don’t see the ring, only the fish, requiring that you know something about the myth in order to fully get the experience of dramatic irony. The balance of white and dark clouds in the sky might symbolize the winds of fate, which blow this way and that depending on the whims of the divine (at least in ancient thought). The balance and harmony of the natural world that Rosa portrays suggests that Polycrates is exactly where he’s meant to be in the cosmos; nature itself is the true ruler here, not him.

Or maybe he just didn’t pass the test by choosing a fairly meaningless ring to give away instead of something truly important. And the gods did indeed have it out for Polycrates, apparently: when Samos was under threat from the Persians, the King of Persia sent one of his satraps (governors) to Samos, where he crucified Polycrates in short order. So Amasis ended up being quite correct that Polycrates was ill-fated. Requital may take some time, but it always comes for the unrighteous.

Harmodius and Aristogeiton, Tyrant-slayers

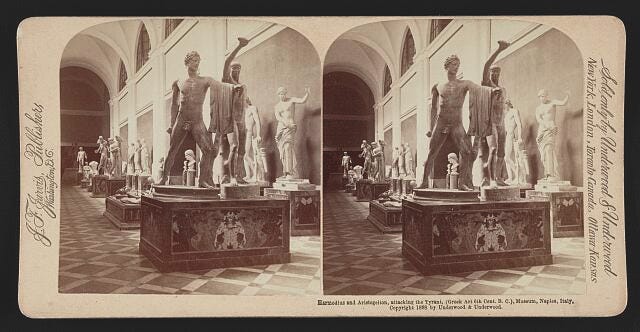

Finally, I wanted to end with the story of Harmodius and Aristogeiton, the famed tyrannicides of Athens. They were said to have been in love with one another as well, and remained a notable example of true love throughout antiquity and beyond. Strictly speaking, they didn’t kill Athens’ tyrant himself, but rather his powerful and influential brother. Although they themselves were executed, their brave act of rebellion against the regime paved the way for the tyrant to eventually be deposed.

There are some lovely statues of H & A in Naples, shown at their defining moment of bravery and resolve:

These two served as examples of heroism and courage; there were songs composed in their honor, and some say their families received special honors from the state after the tyrants had been driven out from Athens.

Thank you for reading this week’s edition of Reading Art!

Thank you so much for reading. I find the topic of kingship in the ancient world to be a fascinating one, and it’s so interesting how so many tyrants were often morally grey figures who were neither entirely good nor bad (but, often, mostly bad). As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts. Take care until next time.

MKA