Valerio Chimentelli's Search for the Classical Past, and My Search for Valerio Chimentelli

Or, that time I accidentally discovered an obscure Renaissance humanist hiding in the Getty Research Institute's Special Collections and embarked on a PhD side quest to learn more about his life

One of the most intriguing things I’ve ever discovered in my academic career happened completely by accident.

In the winter of 2023, I had the good fortune to be accepted to participate in the Getty Consortium Seminar at the Getty Research Institute, which is a course taught on a special topic and led by a Getty Scholar. This was one of the highlights of my graduate experience: I met so many brilliant people and learned some skills that carried me through the rest of my time in grad school, such as handling archival materials and working with them to further my research projects.

It was a drizzly Friday afternoon in the Special Collections Reading Room at the GRI, which is one of my favorite places. Looking out at the library through glass walls, full of readers and researchers, there’s a sort of hush inside the reading room itself. Here researchers are able to study rare books, photographs, and other archival materials close at hand, and there’s a certain thrum of quiet energy, like new discoveries being made in real time.

One of our assignments was to analyze an object or set of material from Special Collections in pairs and then share our findings with the class. It was the day I was supposed to give a presentation to my classmates, the professor, and a GRI curator on a series of photographs of mid-twentieth century China. This was the area of expertise of my partner for the assignment, and I was happy to let her have the spotlight. But she said that she wasn’t able to make it to class that day, and I was feeling a bit nervous about doing the topic justice, being a classical philologist.

But a surprise turn of events not only solved this dilemma, but also led me to an entirely new area of interest for my research.

As it turned out, somehow the twentieth-century photographs didn’t make it out of storage and into the reading room. Instead, there was a seventeenth-century manuscript containing the writings and personal letters of one Valerio Chimentelli, a Renaissance humanist.

Now, I didn’t know much (read: anything) about Valerio specifically, but I knew the manuscript was largely in Latin, and I did know something about the great interest in the classical world that emerged in the early modern period. I don’t exactly remember what I said about the manuscript in the ten-minute presentation, but I think I talked more about ancient intellectual culture than anything else and then more or less connected it to Valerio’s own time!

Before this, I had never really done any kind of archival research, but now I was intrigued. It sounds corny, but the first time I touched a book from hundreds of years ago, I got full-body chills. There’s just something indescribably awe-inspiring about coming into physical contact with the past like that. And just like that, this philologist was addicted to studying material culture, not just reading the edited texts on screens.

Now, this was early 2023, and I wasn’t dissertating quite yet; there was still coursework to be finished. So there was plenty of time to go down some rabbit holes. And thus a new PhD side quest was born!

Who was Valerio Chimentelli? What did he write about? And what was his interest in classical antiquity?

First, some historical background.

Valerio (or Valerius Chimentellius, as he refers to himself in Latin) was Professor of Rhetoric and Greek in Florence and Pisa and a member of the Accademici Svogliati of Florence, which was basically a scholarly association for the learned men of Florence.

There is a very good biography of V. C. in Italian, which provides some more insight—helpful, since I wasn’t able to glean all this by myself just from looking at his papers. Born in 1620 to an affluent lawyer and his wife, he was an avid student of the classics. Later, he was based primarily in Pisa—though he disliked it because he felt the climate adversely affected his health—and was also active in Florence’s intellectual scene as well. Part of his success in the academic/scholarly world was due in part to his good relationship with Ferdinando II de’ Medici.

Chimentelli may have become a priest in his early 40s, and he died from illness in 1668, at age 48.

Like many humanists of his day, Chimentelli was fascinated with the rhetorical tradition of the classical past and, like his ancient predecessors, was very much interested in cultivating and participating in an elite intellectual community. His writings date between 1638-1668. The Getty Research Institute holds a fairly large quantity of his writings, but there are copies elsewhere too—I found references to copies in the Florentine National Library, the Vatican Library, and in libraries in Florence and Pisa, but specifics are a little hard to come by when it comes to V. C. Pisa and Getty seem to have the largest quantity of his writings in one place.

In the Getty Research Institute volume are:

120 letters in Latin and Italian, written by V. C. to Prince Cosimo II and other erudite aristocrats.

38 letters from V. C.’s friends (this is where things start to get interesting)

7 Latin orations, which were delivered at the Accademia Pisana. From the metadata at the GRI: “They include a memorial eulogy of Bartolommeo Vecchi, two encomia on the Medici's patronage of letters, orations in praise of the peace of 1659, as well as discourses on the Greek language and on the question whether solitude or sociability better benefits scholarship.” (Emphasis is mine).

The concept of friendship among the learned seems to be a major through-line of the Chimentelli papers, and this made me eager to learn more not necessarily about Chimentelli’s ideas per se, but his social connections and intellectual life in seventeenth-century Italy.

I found all this so fascinating that I had to go back to Special Collections twice to look at this manuscript. While we do have more information about Chimentelli than we do many other colorful characters of history, there’s not a ton else written about him in the literature, which makes sense because he was kind of a minor player in the grand scheme of things.

Still, to hold (copies of) his letters in my hands and see them with my own eyes gave me the strange sense that I knew him, somehow, and that was even better than reading articles about him.

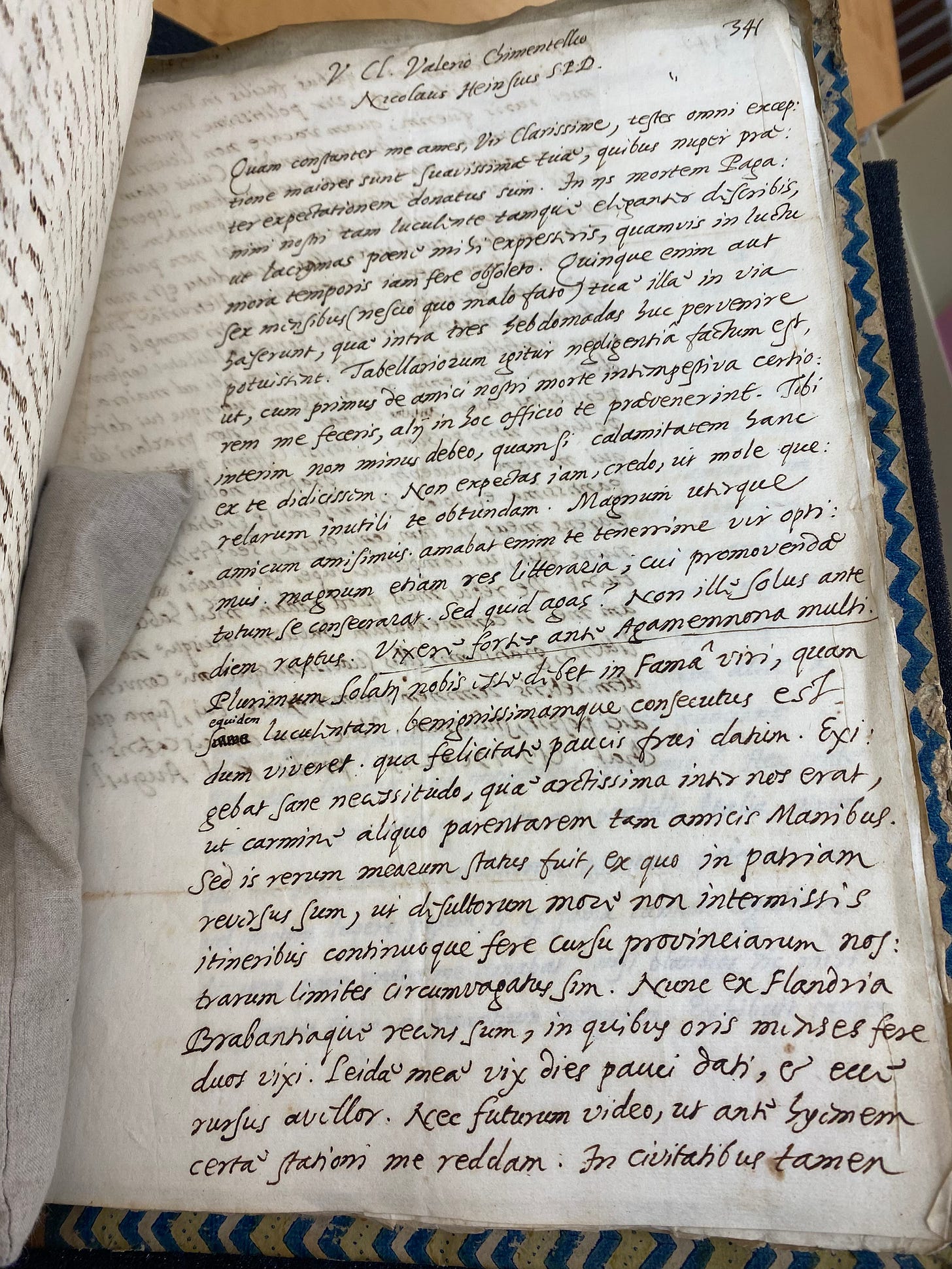

Here’s a Latin letter addressed to Chimentelli and composed by Nicolaas Heinsius, a Dutch scholar, poet, and literary critic who published numerous critical editions of various classical authors. In Latin, the abbreviation SPD was commonly used to start letters, and it means salutem plurimam dicit—literally, “(Name of letter writer) says the biggest greeting.” Isn’t that such a nice way to start things off? So much better than plain old “Dear So-and-So.”

I love how, in a handwritten manuscript, you can see how the scribe would underline things, and even the little variations in their penmanship.

As a side note, the reason we probably have these letters at all is because it was common practice for people to make multiple copies of a letter, so that they could keep records of their own correspondence. These would become like personal archives of a sort, and families might take care to preserve their relatives’ letter collections. A wonderful practice that I feel like we need to bring back in modern-day society!

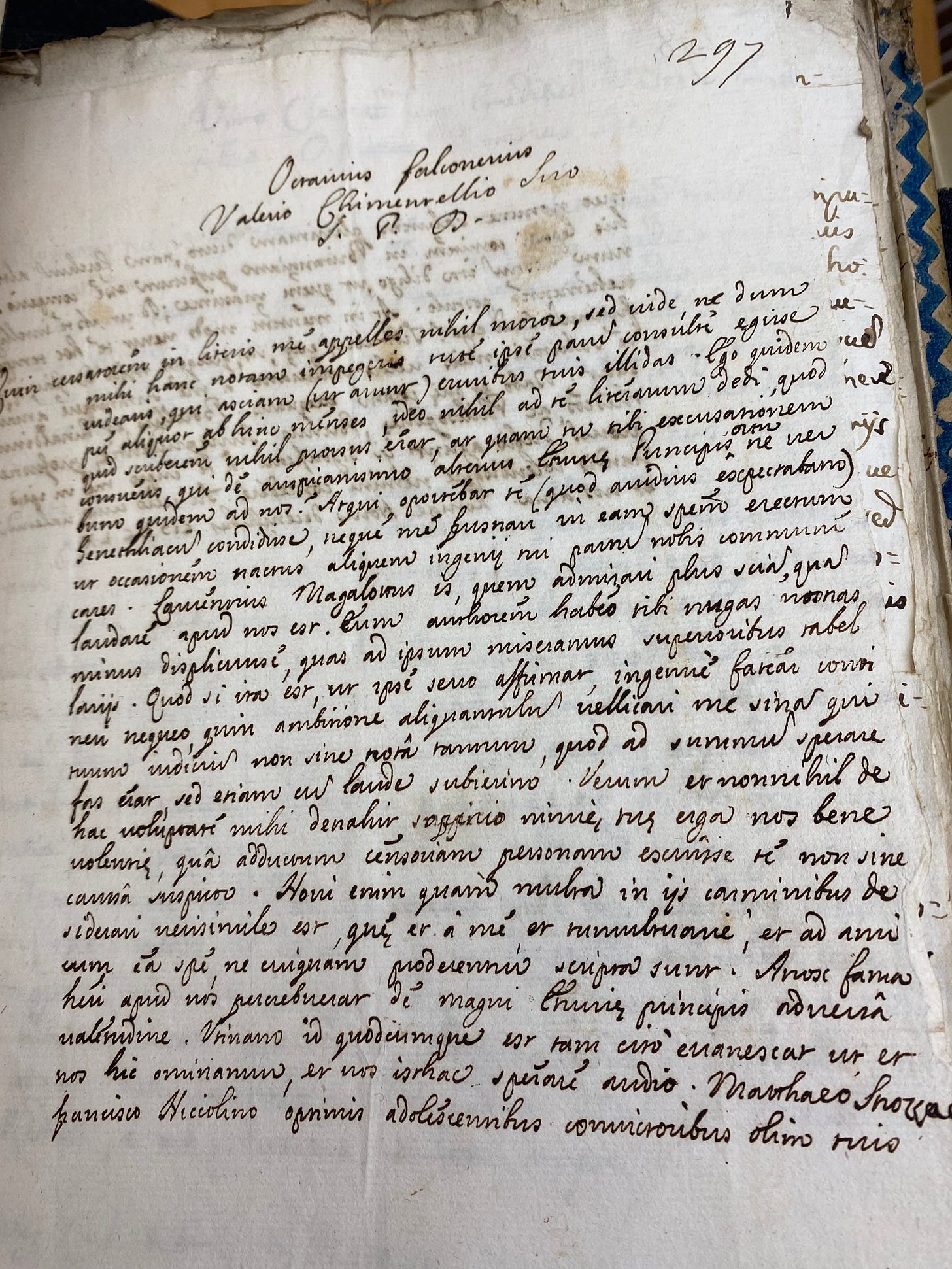

Here’s another Latin letter from one Octavius Palionerius(??). In fact, the word “duo” means there were two letters.

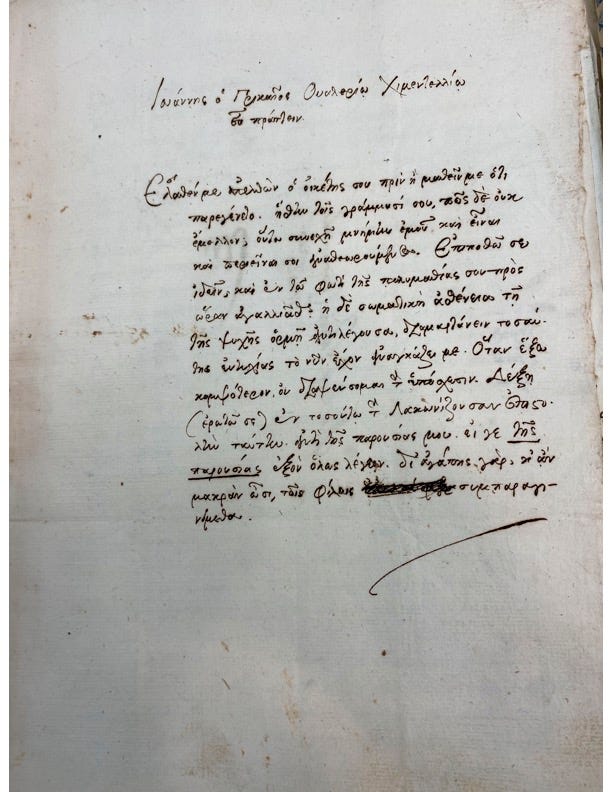

But what really caught my attention was a letter actually written in Ancient Greek:

Not that the Latin ones were easy by any means, but I had a lot of trouble making out the text. I gave it my best shot:

Ιουάννης ὁ Γρικαῆος(??) Ουαλερίῳ Χιμεντελλίῳ

εὖ πράπτεῖν

Ἐλαθέν με ἀπελθὼν ὁ οἰκέτης σου πρίν ἤ μαθεῖν με ὅτι

παρεγένετο. ἥδεω τοῖς γράμμασί σου, πῶς δὲ οὐκ

ἔμελλον; οὕτω συννεχῆ μνήμιω ἐμοῦ καὶ εἶναι

καὶ (τοτὲ?) εῖναι σοι _________ . ἐπιποθῶ σε

ἰδεῖν, καὶ ἐν τῷ φωτὶ τῆς πολυμουθίας σου προς

ὥραν ἀγαλλιᾶ__. ἡ δὲ σωματικὴ ἀσθένεια τῇ

τῆς τυχῆς ὁρμῇ ___λέγουσα __αμαρτάνειν τοσαύ—

της εὐτυχίας τὸ νῦν ἔχον ἀναγκάζεν με · ὅταν ἕξω

κομψότερον, οὐ ________ __ ὑπόσχεσιν. Δέξῃ

(ἐρωτῶ σε) ἐν τοσούτω __ Λακωνίζουσαν ____ ·

λ__ ταύτ__ ___ τῆς παρουσίας μου. εἰγε τῆς

παρουσίας ἐξὸν ὁλως λέγειν. δι᾽ ἀγαπὴς γὰρ, ἠ ἄν

μακρὰν ὦσι, τοῖς φίλοις [word scratched out] συμπαραγε—

νόμεθα.

Johannes (the Greek?? doesn’t sound right, but maybe?) sends greetings to Valerio Chimentelli.

Your servant escaped my notice that he leaving, before I understood that he was even present at all. I take pleasure(?) in your letter, how was I not going to? So constantly do I remember(?) myself(?)

…

I long to see you, and to rejoice in the light of long conversation with you for an hour. But my bodily weakness, speaking(?) by the onslaught of fortune, has compelled me, as it is now, to miss the mark of so great a good fortune; whenever I am feeling better, I won’t…(avoid?)…the undertaking. You will receive (I ask you) in so great…speaking in a laconic manner(?)…

…your presence [underlined]. If only it were entirely possible to speak in person(?). For, through love, we are by the side of our friends, even if they should be far away.

Maybe for the first time ever in my PhD, I felt like a “real” scholar, transcribing (trying to transcribe) this old letter and translating it to the best of my ability. As an added benefit, I gained a new appreciation for the polished, edited texts scholars normally use. Reading manuscripts is not easy AT ALL, especially when the handwriting is kind of questionable like it is here, haha.

No idea who Johannes/John/Giovanni is, and I couldn’t make out his last name!

I love this letter because of the depth of feeling it conveys to Chimentelli. It reminds me of one of Cicero’s letters to his friends—he never held back in telling his friends how much he cared about them, which is something I very much admire about him.

Bodily health is a major trope of letters from the ancient world and, apparently, the early modern period as well. For example, Fronto and Cicero, who both have extensive letter collections, frequently write to their addressees about matters of health. It makes sense: letters are a means of maintaining a connection even when in-person meetings are impossible, such as when one of the two parties is unwell. It also creates a sense of intimacy, allowing our friends and family to see the unpolished and imperfect parts of ourselves.

This raises an interesting question. Does John (let’s just call him that) know he’s self-fashioning as an ancient letter-writer of the past? Or is he just telling Valerio about his health with no more thought to it?

The last sentence I could read stopped me in my tracks: “For, through love, we are by the side of our friends, even if they should be far away.”

This ties in well with the interests expressed in the rest of the Chimentelli papers—the idea that collegiality makes for better scholarship. In the case of this letter, John and Valerio are essentially enacting, performing, or living out philosophical ideals around friendship: they are committed to remaining in dialogue even when they aren’t able to meet in person. One thing to note: it’s not actually letter-writing itself that creates presence in the midst of absence, but love itself—a poignant statement that has equal amounts of philosophical significance as it does raw human emotion.

Ultimately, dedicating oneself to correspondence is a way of life that is rooted in the intellectual tradition, but it also brings a stronger sense of human feeling and creates connections that maybe could not be made by something like a philosophical treatise.

Did I end up figuring out who Valerio Chimentelli was anyway? In some real sense, I did. He was a man who loved and was loved within his community, and he was committed to the pursuit of wisdom. Maybe that’s all I need to know, maybe not—we can’t make him some paragon of intellectual virtue—but the real point was that, by diving into the Chimentelli letters entirely by accident, I learned a lot of new things and brought myself closer to 1600s Italy, a time of rediscovering an appreciation for the ancient world. During a challenging point in my PhD, when I wasn’t sure what I wanted to dissertate on or who I was as a scholar, this exercise offered a rich opportunity to also rediscover what I loved about the classical past.

My side quest also made it even more abundantly clear that I was no paleographer, and it inspired me to take a graduate seminar on paleography!

What historical rabbit holes (or side quests, as the kids say) have you gone down recently? What do you think about Valerio’s self-fashioning as an intellectual of the past? As always, I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

Take care until next time,

MKA

This is very interesting. I have also had my share of difficulties accurately transcribing letters from the archives for research. Handwriting is difficult enough in modern languages where there is proper punctuation. Also, I wholeheartedly agree that letter writing is becoming lost art. I would love to see it make a comeback.

I just came to know of this vir doctus. I am looking forward to delving into his thinking and his world. Thank you so much for making this possible.