The Artist at Work

Scenes of artists in the process of making art: depicting the ever-elusive creative process

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

After looking closely at some of my favorite detail-packed paintings last week, I was thinking more about the process of creating a work of art. Inspiration is a nebulous and fickle companion, but I’m always interested to know more about what goes into making a beautiful work of art.

Unless artists talk about their creative process publicly, it’s difficult to know what inspires them or how they do their work. Maybe the next best thing is to look at a painting of an artist in the midst of creating beautiful. This is the subject of this week’s newsletter: we’ll be looking at scenes of artists at work from the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries, and thinking more about the ways in which these works reflect on the artist’s task.

Jan Steen’s “The Drawing Lesson”

I couldn’t quite say goodbye to Dutch paintings after last week, so here’s another one, Jan Steen’s “The Drawing Lesson,” which portrays an established artist teaching the next generation:

As with many Dutch paintings, there’s a strong element of allegory and symbolism here. The lute and the violin are instruments of creativity, much like the artist’s paintbrush or pen, just in a different medium. The laurel wreath at the lower right hints of fame and artistic triumph, but the skull that extends off the canvas also speaks to the brevity of that fame, as might the disembodied faces and feet hanging in the upper left. Yet the overarching message is that creativity leaves a legacy, not just in the works an artist creates, but also in those who learn from him or her and thus continue to create beauty in the next generation.

The age difference of the two students struck me as well; the boy looks much younger than the girl. They must surely be at different levels artistically, but are taking a lesson together. The boy is looking across at the artist himself; I can’t tell if he looks impressed or bored. But the girl is looking down in awe at the example the artist is drawing. The flush in her cheeks gives her an excited look, like inspiration is slowly dawning as she watches the master at work. And maybe she too will be a great painter in time. I would love to know what it is he’s showing them how to draw—we can’t quite see.

In other instances, however, like our next example, it is possible to see what the artist is working on.

Edward Burne-Jones’ “Letters to Katie”

I mentioned briefly last week that I’m a big fan of epistolography and love looking at letter collections. They are somehow so much more resonant than reading, say, emails or even printed transcriptions of correspondence.

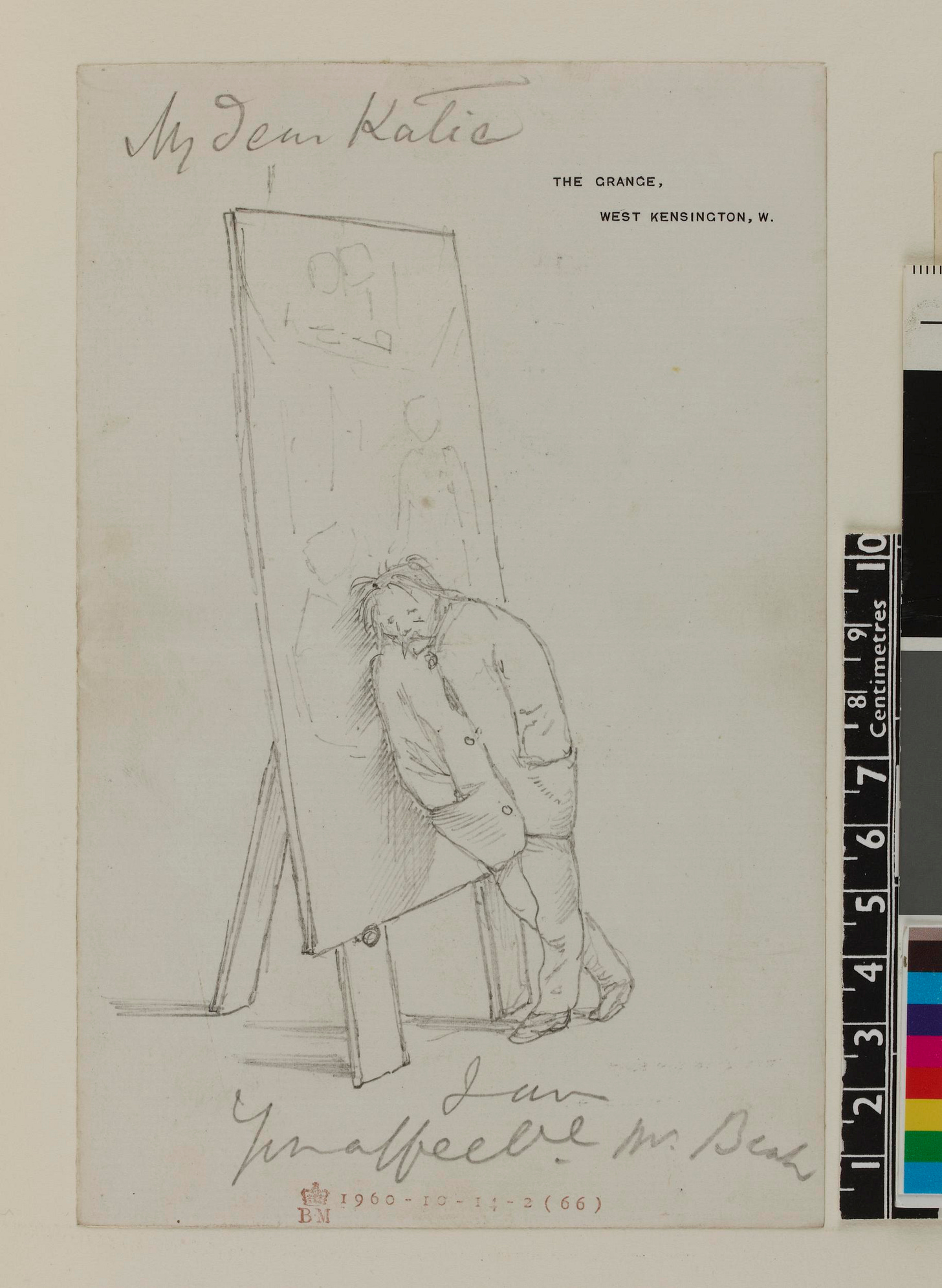

In the sketch below, artist Edward Burne-Jones writes a letter to Katie Lewis, the young daughter of a family friend:

The letter itself reads: “My dear Katie, I am your affecte, Mr. Beak.” Is Mr. Beak a nickname? A joke? Who knows? I assume “your affecte” means “yours affectionately” or some such thing. According to scholarship on this collection, Burne-Jones often wrote things incorrectly as part of an inside joke. But the words are only half of the communication: the sketch does most of the talking.

Burne-Jones seems to have done a quick drawing of himself, leaning in seeming exhaustion against a large canvas. His fatigue seems to explain the note’s brevity in clearer terms than words ever could: he’s been expending all his energy to create a new masterpiece.

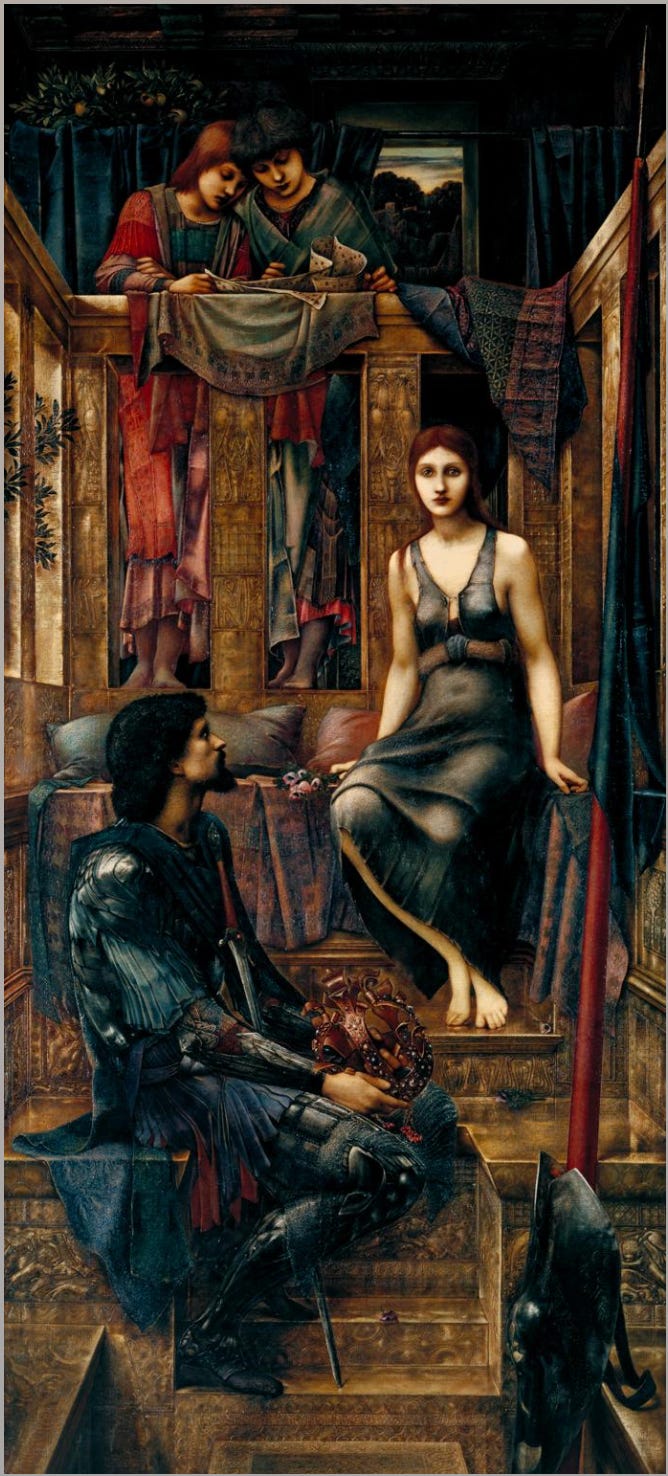

Unlike the Dutch painters above, we actually do know what he’s working on. Fiona Mann has observed that it’s “King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid,” which Burne-Jones produced in the mid-1880s both as an oil painting (below) and also as a watercolor:

This painting depicts an age-old tale in which legendary King Cophetua (known for his lack of interest in women) one day falls head over heels for an impoverished woman he meets on the street when he’s handing out gold coins to his subjects. They get married and live happily ever after, and were even said to have been buried in the same tomb. Maybe I’ll do a future newsletter on scenes of love, because I have so many thoughts. Look at his adoring gaze! But you can also kind of see why Burne-Jones may have struggled with it. How to best capture that indescribable experience of love at first sight? And how long must all the details have taken to render.

Katie Lewis was the young daughter of Burne-Jones’ friend, Sir George Lewis. His letters and drawings addressed to her are often lighthearted. And perhaps King Cophetua’s story would have appealed to her as well. But I love the contrast between the poignancy of the finished work and the dry humor of the sketch of Burne-Jones and his work-in-progress, the juxtaposition of his apparent exasperation and the gentle vision of love we see in the painting. It takes a lot of work to make something sublime, something that looks effortless.

A Self Portrait of an Unknown Artist

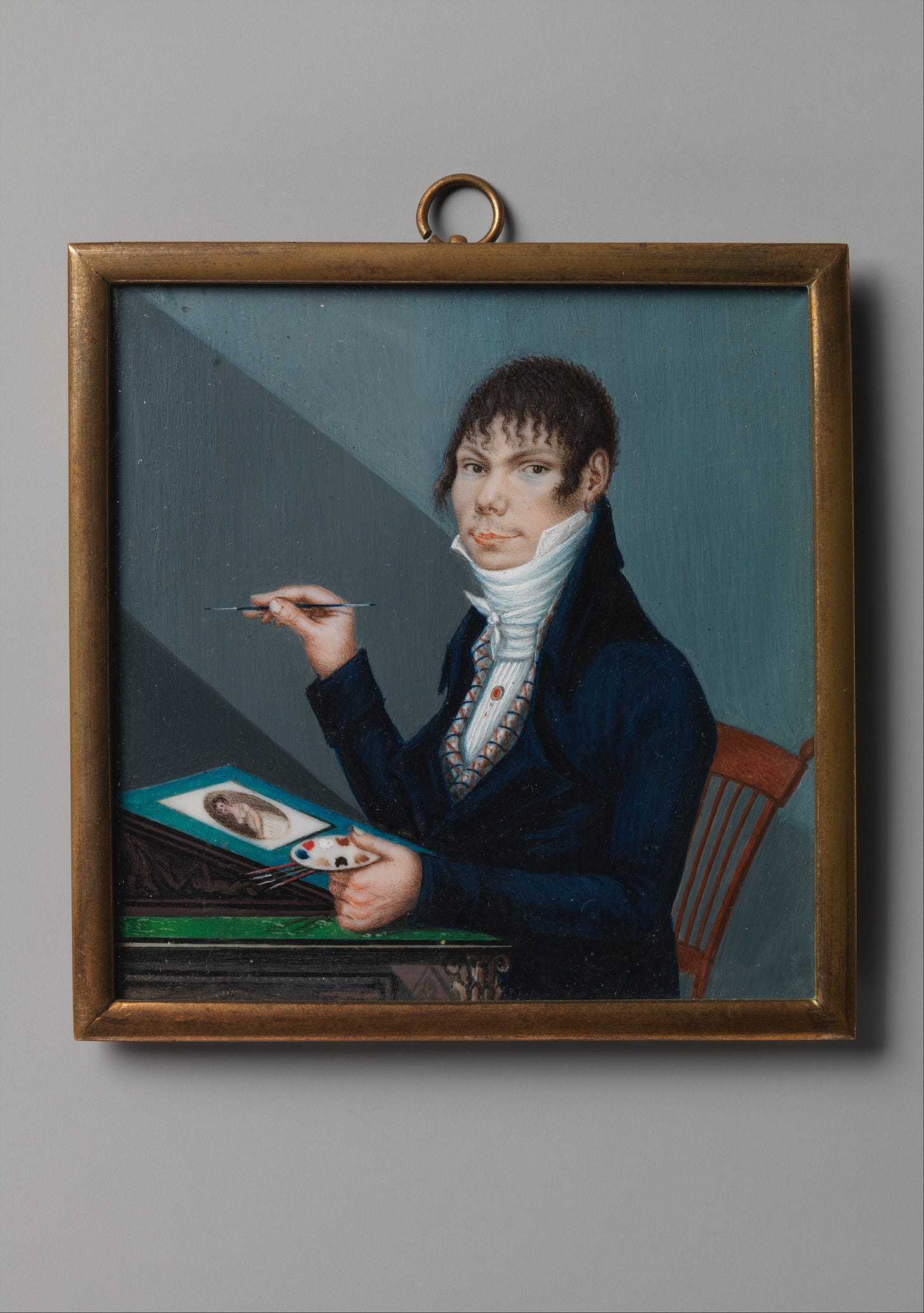

Indeed, being an artist is more of a vocation or a calling than a mere career; this is another reason why I find myself intrigued by images of artists at work. Here’s another example, this time by an unknown artist:

The painting isn’t signed, nor does it have any indications about the identity of the artist. I suppose it’s possible that this isn’t a self portrait, but rather a portrait—but I do love the idea that an artist would want to capture themselves in the process of making art. The work was found in New Orleans, and scholars have suggested that the subject of the painting is biracial.

Whoever he is, he’s clearly been interrupted while painting a portrait of a young woman whose identity is as opaque to us as the artist’s. Is she a friend? His wife? A client who commissioned a portrait? Unclear. Even before we get to the work-in-progress itself, though, the eye goes right to the artist’s right hand, holding his paintbrush, the symbol of the painter’s work. Here, even without a name, we have almost everything we need to know about the subject: his devotion to his craft and his creativity, which is ultimately his legacy.

L. T. P. Manjusri’s “Artist”

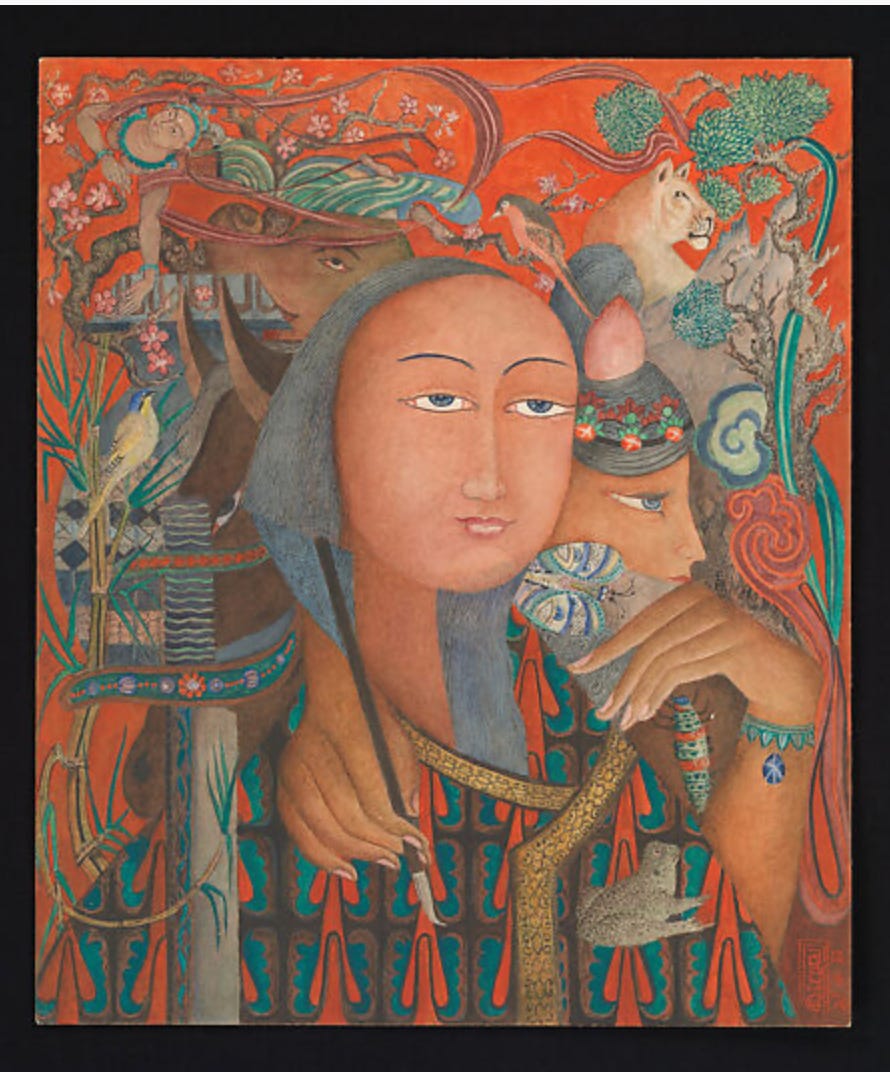

Here’s another instance in which the artist focuses on the hand holding the instrument that will aid in the creation of art: the beautiful “Artist” by Sri Lankan painter L. T. P. Manjusri:

It’s hard to tell who the hand belongs to—is it the woman standing behind the first woman? If so, it’s so interesting how she’s draped around the front figure, as though the she is emerging as a real person from the paintbrush itself: the artist herself can create not just something lifelike, but life itself.

The beautiful animals and plants around the two figures give the painting a surreal yet also comforting quality, as though inspiration exists everywhere, all around. The figures merge with the other elements in the painting, perhaps suggesting the symbiosis between nature and human when it comes to the creative process.

Indeed, being outside in nature is maybe one of the artist’s most natural habitats. To conclude, let’s look at a photograph of some artists rendering a landscape:

F.H. Brigg's’ “The Drawing Lesson-Sketching from Nature”

Here’s another drawing lesson, and this time nature serves as the model for the student. A man, presumably the teacher, leans over a young woman, who is presumably the one learning how to capture the landscape around her:

To sketch from nature is to somehow enliven nature again—not just to imitate it, but to embellish it and make it into a miniaturized version of itself, something that we can take with us wherever we go. And, in so doing, the painter of nature also becomes part of the landscape itself, another example of the close connection between artist and source of inspiration.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter!

It’s always fun to gain some insight into the work of an artist and the ongoing task of getting into the creative flow. From student to established professional, the works we’ve looked at show a variety of creative experiences. As always, I would love to hear your thoughts. Take care until next time.

MKA