Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

Last week, we looked at images of artists practicing their craft. In this week’s newsletter, we turn to portrayals of musicians, creators of art in another form, as well as to the artistry of musical instruments themselves.

Music is a fundamental part of human life. Humans have been making music for time immemorial; it is perhaps the most universal language we can experience. Historically, music was often used for religious rituals, as part of worshipping the gods. For example, we might think of the Homeric hymns composed in the Archaic period in Ancient Greece, each of which is a song that commemorates the birth, heroic deeds, and functions of a specific deity, such as Zeus (father of the gods and god of the sky), Aphrodite (goddess of love), Demeter (goddess of grain and agriculture), or Hermes (god of luck, travel, messages, and thieves). There are numerous other examples from other cultures and time periods as well; the spiritual, transcendental, and otherworldly significance of music is well-documented—and perhaps something you’ve experienced firsthand as well.

Of course, music can sometimes be viewed with suspicion. Think of the skepticism of parents everywhere in the fifties and sixties when rock and roll fundamentally changed pop culture. In antiquity, philosophers argued over whether music could influence the soul for good or bad. And so on. But today our virtual tour will focus on the sublime experience of music.

Orpheus: the archetypal musician

One of the most famous legendary musicians is Orpheus, the son of Apollo (god of music, knowledge, healing, light, prophesy, etc.) and Calliope, the Muse of epic poetry. Orpheus was said to be such a good musician that he could charm humans, animals, plant life, and even inanimate objects like rocks. He traveled with Jason and the Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece and infamously traveled down to the Underworld to try and retrieve his deceased wife, Eurydice. His music was so beautiful that it charmed Hades, the god of the dead, but unfortunately—maybe you know how this goes—he looked back at Eurydice as she was returning from the Underworld, the one thing he had sworn to Hades he wouldn’t do. So back Eurydice went to being dead.

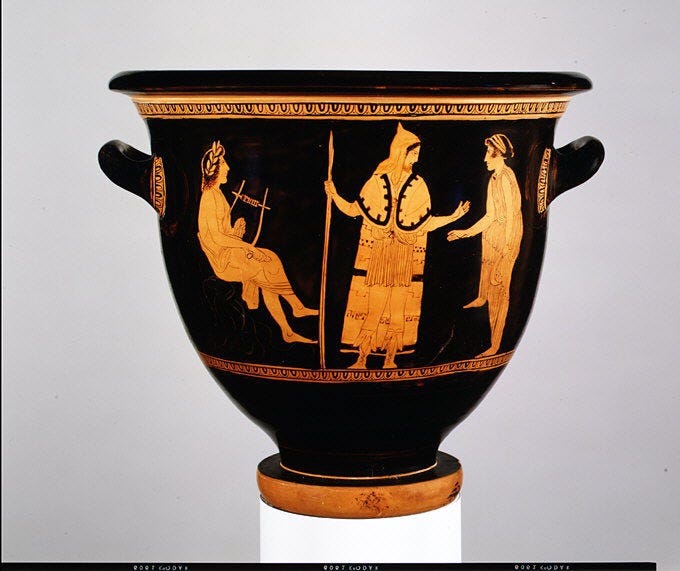

Orpheus is a popular subject for ancient artists. As you can see here, Orpheus (left) is holding his main attribute, a stringed instrument called a lyre:

After losing his wife again, Orpheus was so sad that he traveled from his home in Greece up to Thrace (roughly modern-day Bulgaria) to lead a reclusive life. Some authors are vague about what happened there, saying Orpheus just wanted some solitude. Others are more specific; for example, Orpheus allegedly swore off of women forever and “invented” homosexuality (the ancient Greeks love an etiological story, no matter how far-fetched). In the scene above on the vase, Orpheus is standing with two Thracian women, identifiable from their outfits. You might be wondering: why is one of the women holding a spear? Well, our next object provides a continuation of the narrative of Orpheus among the Thracians:

As the story goes, the women of Thrace were so upset that the handsome and musically gifted semi-divine Orpheus had retired from having romantic relations with women that they decided to attack him, eventually succeeding in killing him and then ripping him apart limb from limb.

In this scene here, Orpheus’ lyre has been cast to the side on his’ right side as one of the Thracian women goes right for the jugular, cutting off any ability to sing so that he can charm them with his voice. Just like with the Eurydice fiasco, Orpheus is a hero who is ultimately unable to use his divine gifts to make anything good happen; he is simply the victim of a brute force that cannot be placated even with the enchantment of song.

I love the harmonious geometric design around the scene, which is fairly standard for a Greek vase, but in this context it seems to nod to the harmony and symmetry of song—which is unfortunately irrelevant here. One can almost imagine the discordant sound of the lyre as it hit the ground.

Lucian (2nd century CE) gives a particularly vivid account of what may have happened next (translation my own):

When the Thracian women tore apart Orpheus, they say that his head, having fallen into the Hebrus River [now known as the Evrus] along with his lyre, was cast out into the Black Gulf, and the head sailed along upon the lyre, singing some dirge over Orpheus, as the story goes, and the lyre itself was playing a melody with the wind falling upon the chords. In this way it was carried to Lesbos with the song, and the people of Lesbos, having taken the head, buried it in the same place where their temple of Bacchus is now, and they dedicated the lyre to the temple of Apollo, and it was preserved there for a long time.

ὅτε τὸν Ὀρφέα διεσπάσαντο αἱ Θρᾷτται, φασὶ τὴν κεφαλὴν αὐτοῦ σὺν τῇ λύρᾳ εἰς τὸν Ἕβρον ἐμπεσοῦσαν ἐκβληθῆναι εἰς τὸν μέλανα κόλπον, καὶ ἐπιπλεῖν γε τὴν κεφαλὴν τῇ λύρᾳ, τὴν μὲν ᾁδουσαν θρῆνόν τινα ἐπὶ τῷ Ὀρφεῖ, ὡς λόγος, τὴν λύραν δὲ αὐτὴν ὑπηχεῖν τῶν ἀνέμων ἐμπιπτόντων ταῖς χορδαῖς, καὶ οὕτω μετ᾽ ᾠδῆς προσενεχθῆναι τῇ Λέσβῳ, κἀκείνους ἀνελομένους τὴν μὲν κεφαλὴν καταθάψαι ἵναπερ νῦν τὸ Βακχεῖον αὐτοῖς ἐστι, τὴν λύραν δὲ ἀναθεῖναι εἰς τοῦ Ἀπόλλωνος τὸ ἱερόν, καὶ ἐπὶ πολύ γε σώζεσθαι αὐτήν.

Unclear if Lucian was being serious or not (probably not, given that he was a lover of satire and absurdity). But still, what a story! Orpheus’ head and lyre continuing to sing even after his death!

Naturally, Orpheus continued to fascinate people for millennia to come, although they tend to emphasize his music while alive. One of my favorite works of all time is the Orpheus Cup from seventeenth-century Austria, made for Emperor Ferdinand III:

The stem of the cup is a gold figure of the Titan Atlas, cursed to hold up the weight of the world forever after Zeus conquered the Titans and assumed his role as king of the gods. At the top are enamel figures not only of Orpheus himself, but also of Artemis, the Greco-Roman goddess of hunting. The cup is richly decorated with animals, foliage, and water, as nature connects both figures. Artemis represents the wild, while Orpheus stands for the ability to tame what is wild with the sublime beauty of music. Emperor Ferdinand was said to have been a lover of music and also a proponent of peace after the Thirty Years War.

I suppose the artists probably weren’t thinking of Orpheus’ gruesome end when they made this piece. Instead, Orpheus gets to exist in a state of serene deathlessness; even the thought of the most beautiful music in the world is enough to immortalize him. There is an implication that music and culture can make toils more bearable: maybe the influence of Orpheus alleviates even the weight that Atlas feels.

Music and the divine

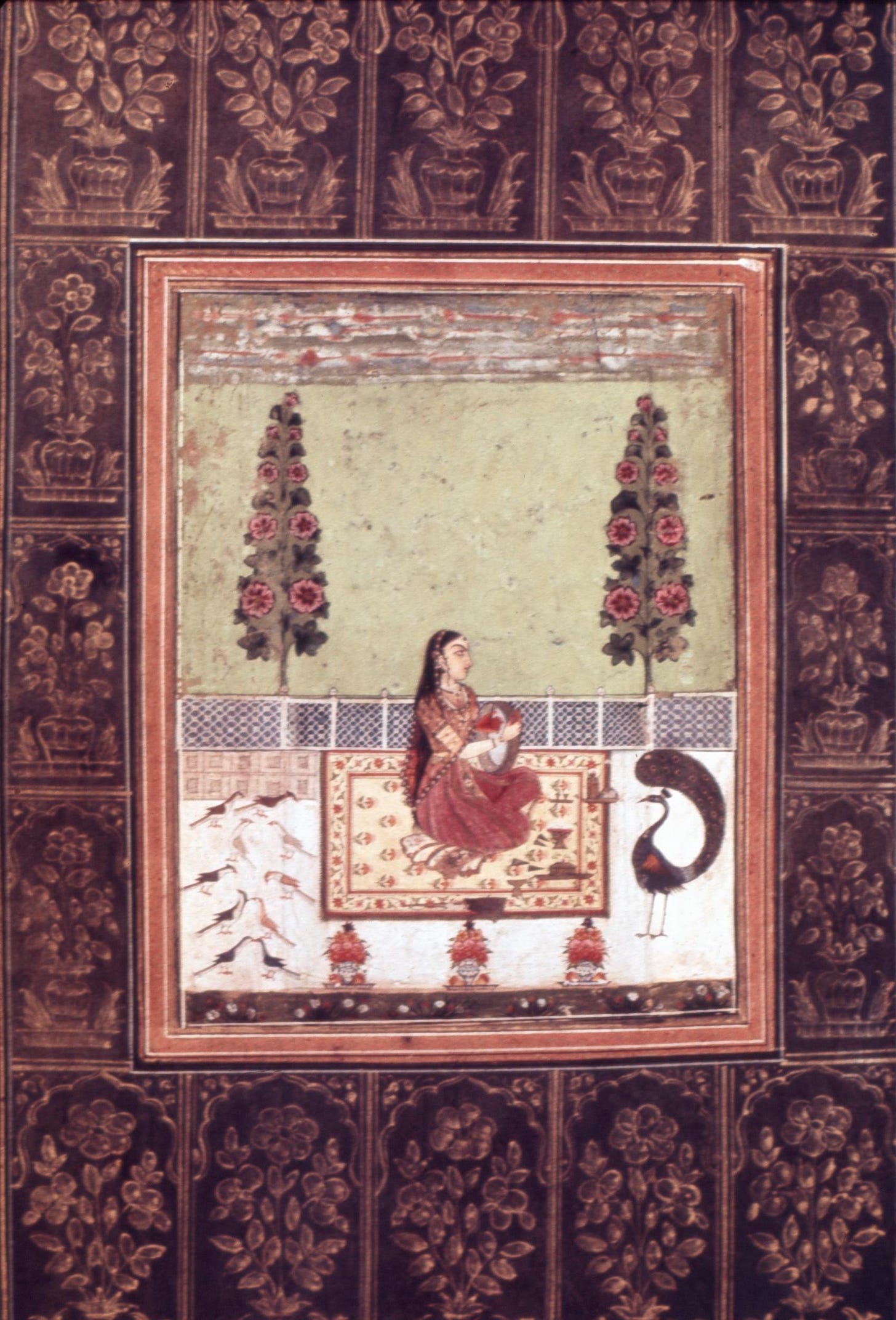

In other cultural contexts, music is associated more directly with women. For example, this beautiful album leaf depicts Hindu goddess Sarasvati playing an instrument, charming the birds around her:

This page is from a compilation of paintings and calligraphy gathered together in the mid-eighteenth century by intellectual Himmat Yar Khan Bahadur, who lived during the Muslim Asaf Jahi dynasty, which ruled over the Hyderabad state (southern/central India) from 1724 to 1948. He held great interest in Indian/Persian culture, a reflection of the cultural interests of his time.

Sarasvati is the goddess of learning and the arts in Hindu culture. She is often portrayed with four hands, but here has two, which gives her more of a human look. To me, this more approachable depiction of the goddess suggests the way in which music can bridge humans with the divine. I also love the array of birds depicted here, from the dramatic peacock on the right to the many smaller birds on the left. Sarasvati herself also looks to be in a kind of meditative state even as she is in the process of playing music.

Thinking about women musicians and the divine experience reminded me of this piece, which I hadn’t given much thought to since my AP Art History days. It’s a statue of two prominent New Kingdom-era Egyptians, royal scribe/physician Yuny (left) and his wife, Renenutet (right):

It kind of looks like Renenutet is holding something shaped like a musical instrument, but that’s technically not what it is—it’s a beaded necklace. But, on the back of the figure, the inscription says that Renenutet was a singer of Amun-Re, the chief god of the ancient Egyptian pantheon. As scholars have noted, these heavy necklaces were sometimes used to create a musical sound, almost like a cymbal, and were frequently used in this way in ritual contexts. Even as simple a sound as beads being shaken together is sufficient to create the soundscape necessary for communing with the divine.

Indeed, women are often play critical roles when it comes to using sound and music to worship the gods. For example, there are a number of acoustic jars from Nigeria and other parts of Africa, such as this one:

This bowl and others of its kind, used by the Igbo and Ijaw peoples, are made of ceramic, and have a small hole in them that allows a sound to be made when they are struck, like a drum. Musicians would use their other hand to cover and uncover the hole in the vessel to shape the sound as it came forth from the jar.

Instruments such as these played an important role in funeral ceremonies. In fact, these kinds of acoustic jars were meant to be played by widows and other female family/community members as they sang in commemoration of the deceased husband. This particular example of an acoustic jar has a lizard motif on its side, another connection between music and the natural world. Even at a time when things feel most hopeless—the death of a spouse—music helps restore some order to the world. Similarly, in a religious/ritual context, music helps send the deceased onto the afterlife, once again connecting the human with the divine.

Indeed, in addition to being an important part of divine, religious, and ceremonial experiences, the presence of musical sound also creates an otherworldly experience even in otherwise mundane circumstances. I want to wrap up with this sixteenth-century jug, which combines both of these aspects into one object:

On the one hand, this jug might have been a functional item, if not used in everyday contexts then at least on special occasions. But the images on the jug speak to a much deeper experience, bringing that feeling of hearing beautiful songs into daily life. On the front, there is a man in sixteenth-century style dress, playing a lute. There is also an image of Orpheus playing an Italian version of a lyre. Depicted in the third scene is Old Testament prophet Elisha, who, according to legend, heard the music of an unspecified string instrument and then fell into a deep trance. He then began a very doom-and-gloom prophesy.

Perhaps the parallel with Orpheus is more clear after looking closely at Orpheus mythology: music is powerful, but it does not always lead to pleasant things—still, in the case of Elisha, music is that critical conduit for divine knowledge to be transmitted, even if that knowledge isn’t good news of any kind.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter!

I hope you enjoyed this week’s exploration of musicians and music across time periods and cultures. This selection of objects really emphasize that there are many parallels to be made: music truly is a common “language.” I wonder what it would be like to hear the music of Orpheus, or Renenutet, or even the song Elisha heard! Collectively, these objects offer a visual experience that invites in another sense, sound, making our engagement with them almost synesthetic as we use our imaginations to fill in the gaps. As always, I would love to hear your thoughts. Take care until next time.

MKA