Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

It’s hard to believe it’s Thanksgiving this week again already—the year has flown by—and thus the real start of the holiday rush. Autumn is by far the best season, in my opinion, and is also the most aesthetically pleasing season in art. Read on for fall colors and cozy vibes.

In the works we’ll look at today, we really get a sense of the way that autumn is a time of abundance and fulfillment of many toils, and it can be a kind of chaotic time as well: end-of-year busyness, unpredictable weather, and the scramble to make the most of both the waning daylight and the waning year.

Scenes of Autumn

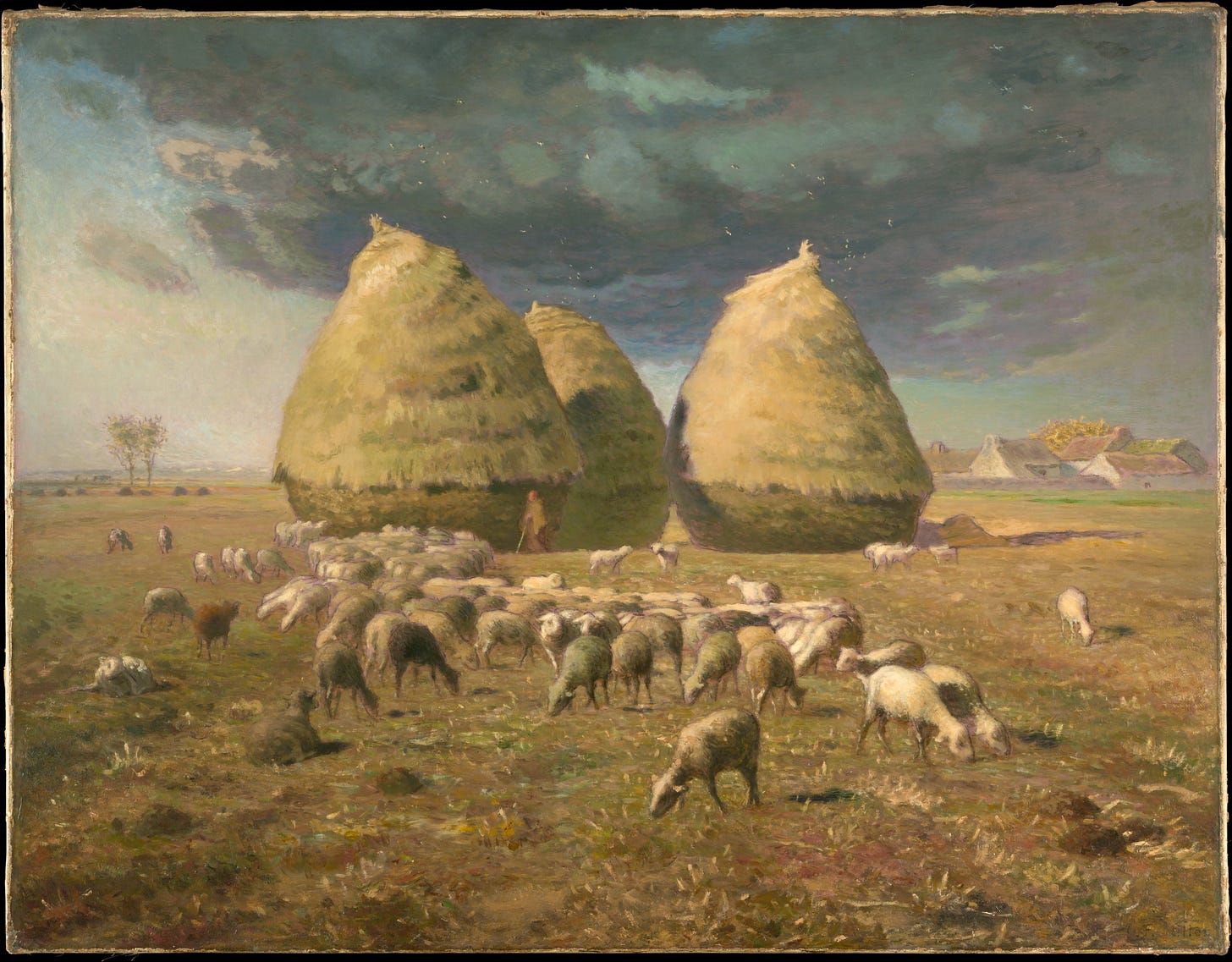

Pumpkin spice lattes and Ugg slippers might be staples of the cozy season in modern times, but before those now-timeless symbols of the season there was the classic haystack and flock of sheep:

In the late 1860s, industrialist Frédéric Hartmann commissioned four paintings from Jean-François Millet, each one depicting one of the four seasons. I suppose he enjoyed looking at images of nature and pastoral harmony even as industrialism threatened it, but we’ll save that for another time. Here’s the painting for autumn: the giant haystacks loom large in the background, the harvesters have left for the season, and the sheep remain to clear up what’s left. The dark sky foreshadows a stormy winter, and there’s a sense of wrapping things up for the year so that everyone can finally take a break during the winter months. I love the sculptural look of the haystacks, almost like their own art installation.

The style of the work is almost impressionistic; it hovers between precise and sketch-like. As the Met notes, you can see the underdrawing on the haystacks and the sheep, which is so interesting. Even as autumn is a time of completion and everything is getting wrapped up for the year, the portrayal is slightly unfinished. It’s almost metaphorical: winter may be on its way, but that fallow season is not without its toils as well.

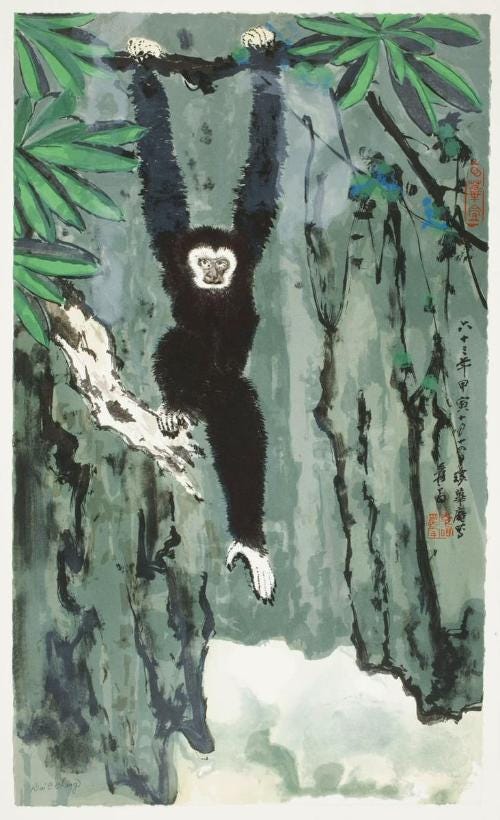

We might think of fall as a time characterized by warm tones of gold, orange, and burgundy, but there are other color schemes that reflect its vibe just as well, such as this wonderful late-twentieth century painting by Zhang Daqian:

I was perusing the collection at the Asian Art Museum, in hopes of going in the nearish future, and really fell in love with this one. A gibbon is kind of like a smaller ape or larger chimp, weighing 10-30 pounds or so. The inscription on the right side of the image reads: “Painted at Huanbi’an on the fourteenth day of the tenth lunar month in the jiayin year (1974), or the 63rd year (of the republican period). The old man Yuan.”

The title of the work also intrigues me: what makes a stream an autumn stream? Simply the time of year? Or does the season affect the way the stream appears, or the way one interacts with it? Maybe autumn rain makes the stream swell, or the cooler weather makes the stream too cold to splash in. Or something else entirely.

The cool green, grey, black, and cream of the drawing makes it very atmospheric, and it would be moody if it weren’t for the cute little gibbon swinging over the water. While the Millet painting above speaks to toil, this one speaks to play: autumn is also a time to let yourself be reinvigorated. It’s a time to be with family and enjoy the abundance of harvest season, but maybe also a time to seek solitude and have some fun without any rules, like the gibbon.

Indeed, in looking at so many scenes of fall, it seems to me that artists frequently like to create a sense of solitude when depicting this time of year. This Inness painting really captures the balance between togetherness and solitariness:

The first thing we see is the trees, changing color to signal the oncoming winter. Again, the purple tones of the sky, like the Millet piece, suggest that a cold and stormy time of year is approaching. But then my eye wants to settle on the sunlit fields, rendered in green and gold, and then there’s this wonderful realization that this is not simply a stately scene of nature’s grandeur: we see that we are not alone, but rather there is an ample flock of cattle and, in the distance, a man stands in the middle of an open field. Even in the sky that threatens rain, white birds fly together. Even the trees no longer seem so imposing; they too are company with whom to delight in the splendor of fall.

There’s a certain peacefulness to the scene that brings it a sense of levity as well. Work is not being done; it has been done already. It seems like the landscape itself has taken a sigh of relief and can now just enjoy the time of year. Certainly an aspirational feeling!

Autumn rituals

Autumn kicks off the holiday season, and has traditionally been a time of ritual and celebration in community together for thousands of years. In general, these rituals, somewhat like our own modern Thanksgiving, revolve around gratitude for nature’s generosity. Oftentimes, this involved the worship of a specific deity.

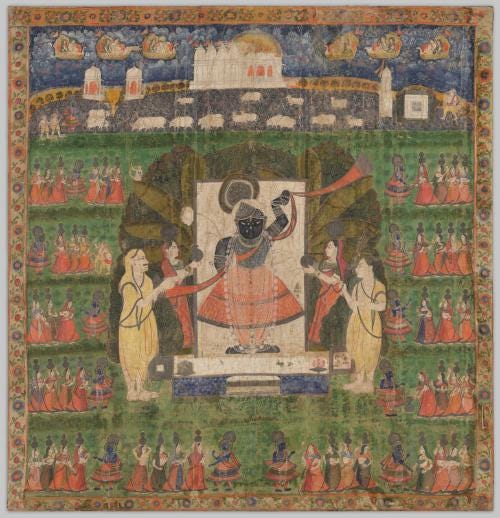

As I mentioned, I was looking through the Asian Art Museum’s collection, and came across this watercolor depicting the Hindu autumn moon festival, Sharad Purnima:

Sharad Purnima involves prayers, giving thanks, spending time with family, and dancing under the moonlight. Other South Asian cultures also hold mid-autumn moon festivals as well, all generally taking place some time in October. Here, the crowds of people with the livestock at the top of the image give the work a sense of the busyness of a festival, and yet the linear rows of the work also give it a sense of order. Krishna stands prominently in the middle, receiving offerings of butter. (Interestingly, there are other images of Krishna eating butter—maybe a topic to explore in more depth another time.) A god of protection and compassion, among other things, he seems an ideal figure to pay respect to during an autumn festival that celebrates community and abundance.

There’s such a great sense of motion here as well with Krishna’s red drapery picking up on the red garments of the smaller figures who surround the central scene, and the green creates an impression of the richness of the natural world as it contrasts with the red.

Turning to ancient Mediterranean antiquity for a moment, they too loved a harvest festival. This engraving from the late eighteenth century captures a similar whirling sense of movement, but also has more of an aloofness to it:

Ceres, the goddess of grain, and Dionysus, the god of wine, were two deities commonly worshipped in the fall for obvious reasons, and the two were often linked as agricultural gods. Here, Greek maidens and youths dance, and there are some wrestlers off to the left of the scene, indicating perhaps a local competition to accompany the other festivities.

I love the peacock (or pheasant?) in the upper left, and the children playing near a bunch of grapes in the lower left-ish center. The level of detail is incredible. It seems in the upper left there might be some divinities looking down upon humanity, as a reminder of who is responsible for all and any human prosperity.

Here, I continue to be struck by the interplay between simplicity, solitude, busyness, and extreme detail in these autumnal scenes. For example, take this painting by Samuel Hieronymus Grimm (relation to the Grimm brothers unknown), who was known for his love of detail, especially details with historical significance. This work has all the usual hallmarks we’ve seen:

It’s got haystacks, some buildings, a stormy sky, a water element, and some livestock. All looks o be going well; the work of the harvest is underway. But not for everyone, apparently. Peep the lower left corner: there’s a woman about to hit someone with a small pitchfork. She looks very angry—I guess he fell into the “hardly working” category as opposed to the “working hard” one, like the people over to the right. The small-scale violence casts a bit of a pall over the whole scene. The building in the center also features so prominently that it makes me wonder what exactly it is. Is it a town hall of some kind? A center of commerce? Who knows. The spire gives it an official, righteous sort of look, maybe mirroring the woman about to punish the shiftless. The painting is from 1776, so maybe tensions worldwide were running sort of high. Or perhaps Q4 is just a stressful time for everyone.

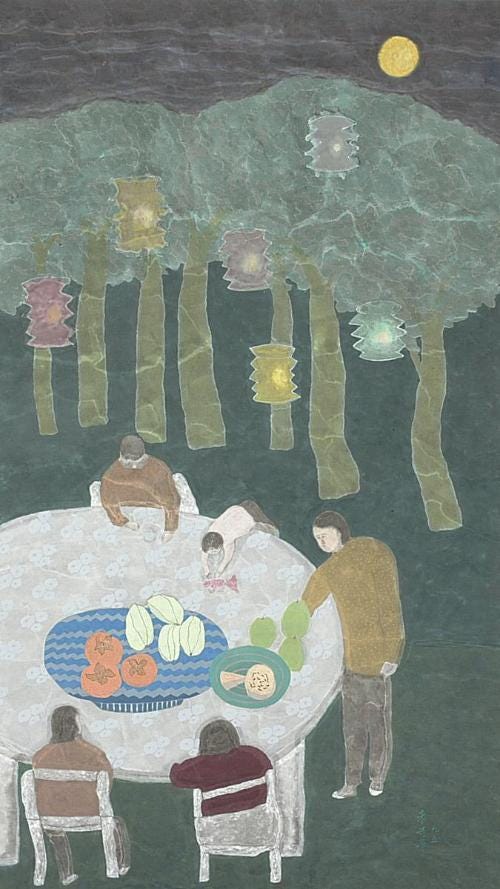

But I want to end our virtual tour for today with an image of serenity, harmony, and family bonding. I love this work, “Mid Autumn,” by Zhu Xinghua:

Here’s another work celebrating the mid-autumn moon and the abundance it brings, this time in a near-contemporary context. The lanterns hanging in the trees are so luminous that you can almost feel the warmth of their light; the 90s normcore looks and hairstyles are perfection. I love the child climbing up onto the table, and the pleasing colors of the fruits. Eating outside this time of year can feel like a rare luxury, but the forest and the lanterns seem so inviting, and the yellow harvest moon is more perfect than any lighting fixture in an indoor dining room. Even the table has s subtle floral motif worked into it, making it seem like the table is part of the natural world too. The sky is dark, but the mood is light: the emphasis is on family, enjoying the season together: the perfect way to spend dark autumn nights, in my opinion.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter!

I hope you enjoyed this week’s edition of Reading Art. Happy Thanksgiving and warm wishes for a cozy week ahead. Take care until next time.

MKA