Reading Art Book Club: Introduction to Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy

Make philosophercore your vibe this summer :)

June is here, school is out(!), and it’s time to kick off the first round of Reading Art Book Club!

For the next several weeks, we’re going to be reading Boethius’ sixth-century iconic work Consolation of Philosophy, book by book. I’m excited! As a classical philologist and intellectual historian, my research has primarily focused on the first-third centuries CE, but I’ve found myself really drawn to late antiquity/the Medieval period in the last year or so. And I’ve never read Boethius’ Consolation all the way through.

By now, if you’re joining us (and no pressure to keep to the schedule—highly encourage going at your own pace always!), I hope you’ve gotten your copy of the text and have had a chance to flip through the Introduction.

As a reminder, here’s the complete schedule:

Now-June 16: Acquire the text. I’m using the Penguin Classics edition, translated by Victor Watts. This edition is readily available wherever you buy books, and there is a Kindle edition available as well!

June 16-June 22: Book 1 (pg. 3-21)

June 23-June 29: Book 2 (pg. 22-46)

June 30-July 6: Book 3 (pg. 47-84)

July 7-July 13: Book 4 (pg. 85-115)

July 14-July 20: Book 5 (pg. 116-137)

So, we start on Monday! For today’s post, I’m going to give a brief introduction to Boethius, his historical context, his intellectual background, and the structure of the Consolation. I hope this will help you get oriented with the text before we dive in.

Biography and Historical Context

Boethius (full name Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius) was a Roman of aristocratic birth living under the rule of King Odoacer, the Germanic king whose conquest of Italy was seen as the end to the Western Roman Empire. It seems that Odoacer fashioned himself as a client of the ruler of the Eastern Roman Empire, but for all intents and purposes he was the sovereign of Rome. Later, King Theodoric the Great, ruler of the Ostrogoths, overthrew Odoacer and established himself in the role of rex (king) and dux (leader of the armies). Not a Roman emperor, but also not not a Roman emperor-like figure.

So Boethius lived in the time sort of immediately following the late Roman Imperial era, and he sits somewhere between late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. This period in general was a time of flux, when Rome was caught between the classical past and the Christian future of the realm. Born in 420 to a distinguished patrician family, Boethius—unlike many of his peers—seems to have been a Christian from birth.

Boethius’ father died when he was a child, and he was raised by another aristocratic family: the household of Quintus Aurelius Memmius Symmachus, a prominent statesman usually referred to as Symmachus. This Symmachus was a Christian as well, though his grandfather (also named Symmachus) was a staunch upholder of traditional Roman polytheistic religion.

Later, Boethius married Symmachus’ daughter, and Symmachus is credited with being the one to introduce Boethius to the liberal arts. Boethius himself was thought to be a natural student of philosophy even from a very young age.

But he didn’t just live the life of the mind. Under Theodoric the Great, Boethius’ political career flourished, and, after making consul at only 30 years old, he soon became the magister officiorum, which is kind of like being the royal chief of staff, with additional responsibilities.

During this period of Boethius’ life, he devoted himself to the study of the classical past and completed translations and/or commentaries of Aristotle, Cicero, Porphyry, and other ancient authors, in addition to books on philosophy; his particular area of expertise was logic.

At first, Theodoric and Boethius seemed to get on very well. Theodoric too was a Christian, although he adhered to the Arian school of thought, which denied that Jesus was the Son of the Father—instead, this school taught, Jesus was created by the Father, a key theological difference. Even back then, this was considered a heretical idea.

As he aged, Theodoric grew more and more suspicious, and his position (or so it seemed) became less stable. There was allegedly a plot against Theodoric, and, in his capacity as magister officiorum, Boethius apparently didn’t give the matter its due attention and even tried to brush it off. As a result, he became implicated in the scheme, and in 524, at age 44, he was tortured and executed after being imprisoned for some time.

It was during this troubled time that, like a swan song, he wrote what is widely considered to be his greatest work: the Consolation of Philosophy. In this work, the deeply troubled Boethius imagines that Philosophy, personified as a beautiful woman, comes to deliver solace to him. In the course of this dialogue, the two explore many topics of moral and philosophical significance.

Intellectual Background and Influences on the Text

Although Boethius was a Christian from birth, some have questioned this religious identity due to his great ardor for the pagan intellectual greats of classical Greece and Rome. In addition, the Consolation does not really mention Christianity in very direct terms. It’s obviously a Christian text, but it can be distinguished from works such as those of, for example, St. Augustine. In other words, a Christian perspective is very evident, but discussion Christian doctrine per se is…not, a “problem” that continues to challenge scholars.

What this means for us, functionally, is that there is extensive discussion of God etc., but not so much doctrinal questions, e.g. “if Jesus is the Son of God, why did he experience human emotions,” like other Christian authors of late antiquity and the Middle Ages (and onwards) grappled with.

Indeed, the trope of philosophy as a consolation to humanity in its woe-begotten state has a long history. Centuries before Boethius, for example, Epicurean philosopher Lucretius had described philosophy as a medication for the human spirit, and you see this idea echoed in Seneca and Cicero, among several other ancient authors.

There are several genres that influenced Boethius:

Philosophical dialogue, the form of philosophical treatise made famous by Plato (and, arguably, his teacher Socrates)

The consolatio or solacia (see above)

Classical mythology: in the absence of writing explicitly about Christianity, Boethius actually draws on several figures from pagan myth to make broader points about morality, ethics, and philosophy.

Ancient literature (see pg. xxii in the text): in the work, there are references to Catullus (poet), Claudian (poet), Euripides (tragedian), Homer (epic poet), Juvenal (satirist), Lucan (poet), Menander (comic poet), Statius (poet), Seneca (tragedian and philosopher), Ovid (love poet), Sophocles (tragedian), and Virgil (epic poet).

Allegory: not really a genre, but Boethius makes frequent use of allegory to make philosophical points, a notable feature of much of Greek and Roman wisdom literature.

As Watts notes (pg. xxxiv of the text), “[Boethius] belonged to an age in which the ancient classical culture had become assimilated to Christianity, but not absorbed by it.” In other words, they lived in a kind of uneasy harmony in which Christian authors were able to find the bits and pieces of pagan culture that appealed to them and could be rationalized with Christianity, even if their authors were not Christian.

It’s also important to talk about the form of the text. It’s composed as a Mennipean satire, which alternates between poetry and prose.

Stylistically, this is quite nice, as it allows for Boethius to express himself creatively and then rationally in turns. As the name suggests, this form was generally, in antiquity, reserved for actual satires. For example, Seneca the Younger wrote Apocolocyntosis, "Pumpkinification,” a satirical work, and it is also seen in Petronius and other satirists writing mocking and humorous works.

So why would Boethius choose it for such a weighty text?

Well, in my opinion, it’s basically about flouting Theodoric’s authority. Satire in general usually mocks convention, those in power, stereotypes, etc.

That’s not really the case here; there’s nothing openly satirical about the work. But by using the Mennipean satire here, maybe Boethius is making a greater metaliterary point about the transience of death and the ultimate meaninglessness of Theodoric’s punishment compared to the power of God—and Philosophy’s ability to carry her students directly to heaven through her sage wisdom.

Altogether, the Consolation is a reminder that it is possible to rely on a combination of reason, wisdom, and faith to get through all and any adversities in life.

As a very brief tangent, I love this Medieval posy ring with the inscription "YELD * TO * RESON *” (i.e., “yield to reason”) plus the initials “TA.”

The British Museum speculates that this might have been a nod to the Consolation; only by “yielding to reason,” as it were, can we weather life’s storms. And someone liked it well enough to wear this little snippet of wisdom! So interesting. Anyway, onto the text itself.

The Structure of the Consolation

The work is structured into five books:

Book 1: Boethius is sad and Philosophy comes to comfort him.

Book 2: Philosophy and Boethius talk about the uncertainty and unpredictability of Fortune

Book 3: The nature of true happiness

Book 4: Why God allows bad things to happen to good people and how evil works

Book 5: Providence, free will, and predetermination

Each week, we’ll dive into one of these five books!

The Legacy of the Consolation

This text was hugely popular in the Medieval and early modern periods (and still is today!). It was translated and studied by the likes of King Alfred, Chaucer, John the Chaplain, and even Elizabeth I, among many others.

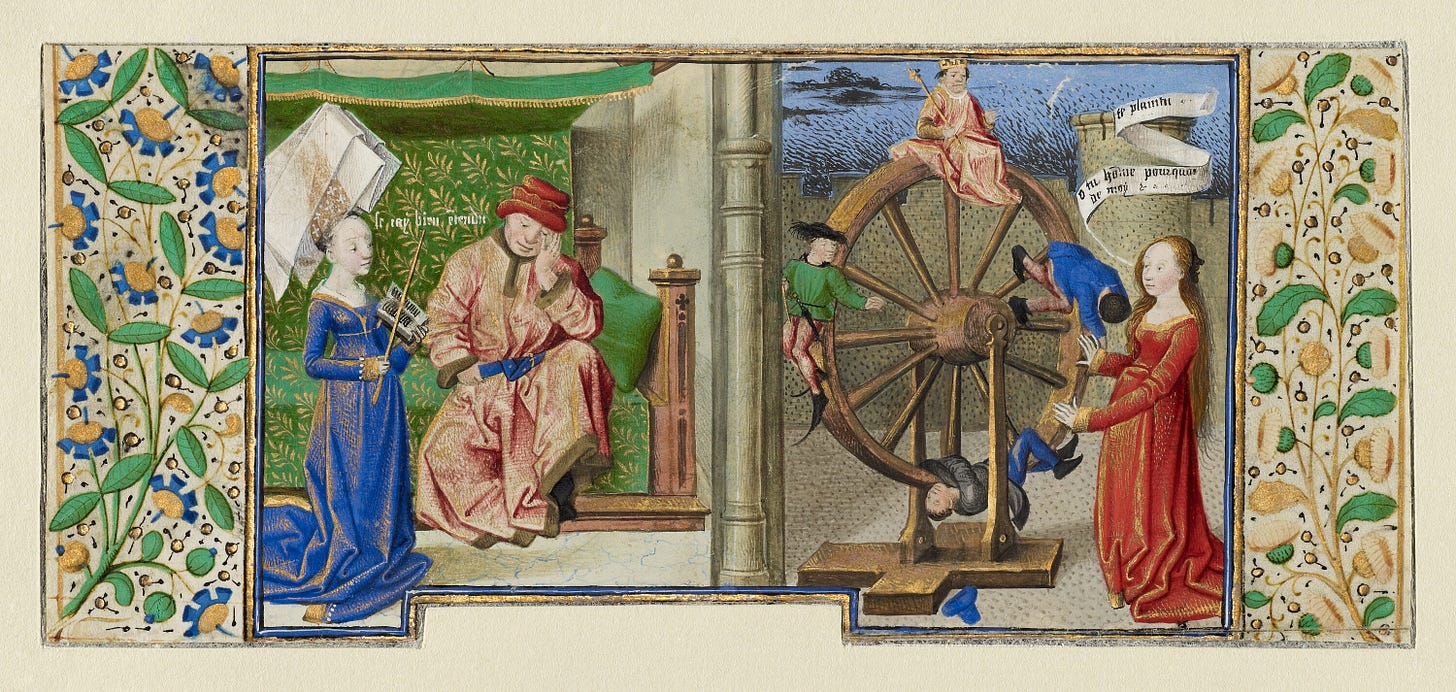

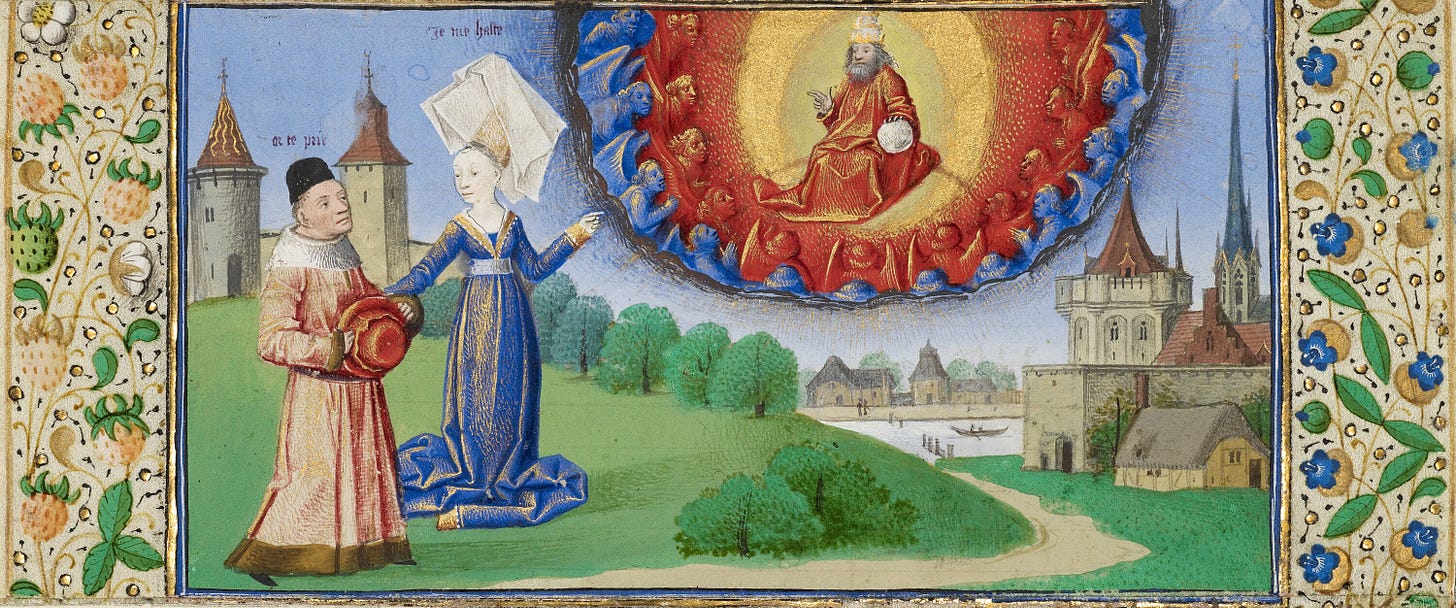

It was a popular text during this time, and there are some beautiful manuscripts.

The Getty Museum has a series of miniatures from a fifteenth-century French copy of the text, which are absolutely beautiful:

Please share this with anyone you know who’s interested in a five-week philosophy journey this summer! I’m really looking forward to seeing what wisdom Boethius and Lady Philosophy have in store for us. I’d love to hear from you in the comments.

Take care until next time,

MKA

This is great. I look forward to reading along and learning more about Boethius' contributions to philosophy.