On Microdosing Philosophy: Moral Improvement for Busy People

It's never too soon or too late to improve your life—a rare point that both Epicureans and Stoics agree on! Plus, what I'm personally doing to keep philosophy in my routine during a busy season.

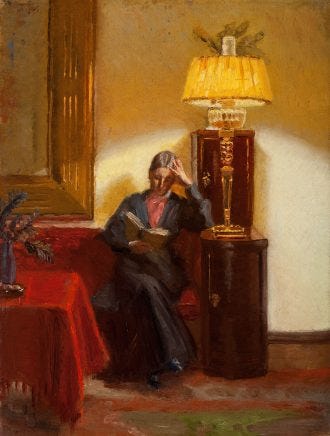

In a recent essay on Reading Art, we explored the humorous world of the philosopher Theophrastus’ so-called “characters.” To recap, this is a text that describes a list of 30 fairly negative traits that the philosopher used as the centerpiece of a colorful treatise on human morality and the different personalities that are observable among the Greeks. These traits were mostly bad, objectively speaking, ranging from Greed to Penuriousness to Rudeness.

But one of these wasn’t bad at all, in my opinion: Late Learning. This trait describes someone in middle age or later who suddenly discovers a zest for learning everything possible about a given subject, whether that’s an intellectual discipline or something more physical, such as playing sports.

Now, Theophrastus kind of pokes fun at this stereotypical character, since this imaginary persona is usually found bustling around trying to take in as much as he can all at once. But I found myself quite admiring the Late Learner, and it reminded me of the recent pop culture trend of creating a personal curriculum, which is kind of like designing a syllabus for yourself to learn about something new in a way that is structured, yet does not rely on enrolling in a formal class.

With all the barriers (primarily financial) to enrolling in college courses, especially after that ship has already sailed in your life and you’ve already collected one or even several degrees, I’m a big fan of this trend!

I was immediately reminded of Epicurus’ Letter to Menoeceus, which starts out with a discussion that seems relevant to the points above (link to English translation by Cyril Bailey here, Greek text here, the following translation is my own):

Let no young person delay to practice philosophy (literally philosophein, ‘to do philosophy), and let no old person who has undertaken philosophy become tired of it. For it is never the wrong time of life for someone to see to the health of his soul. But the one who says that either it’s not time yet to practice philosophy or that time has passed him by is like the one who says that it’s either too late or too early for someone to experience happiness. Resultantly, it is imperative that both the old and the young practice philosophy; for the old become young when they feel a sense of fondness at remembering the good things of the past, and both young and old alike because they have no fear of the future. Therefore, it is necessary to have a care for the things that create happiness, especially since we have everything when happiness is present, but when it is absent we do everything we can to acquire it.

μήτε νέος τις ὢν μελλέτω φιλοσοφεῖν, μήτε γέρων ὑπάρχων κοπιάτω φιλοσοφῶν. οὔτε γὰρ ἄωρος οὐδείς ἐστιν οὔτε πάρωρος πρὸς τὸ κατὰ ψυχὴν ὑγιαῖνον. ὁ δὲ λέγων ἢ μήπω τοῦ φιλοσοφεῖν ὑπάρχειν ὥραν ἢ παρεληλυθέναι τὴν ὥραν, ὅμοιός ἐστιν τῷ λέγοντι πρὸς εὐδαιμονίαν ἢ μὴ παρεῖναι τὴν ὥραν ἢ μηκέτι εἶναι. ὥστε φιλοσοφητέον καὶ νέῳ καὶ γέροντι, τῷ μὲν ὅπως γηράσκων νεάζῃ τοῖς ἀγαθοῖς διὰ τὴν χάριν τῶν γεγονότων, τῷ δὲ ὅπως νέος ἅμα καὶ παλαιὸς ᾖ διὰ τὴν ἀφοβίαν τῶν μελλόντων· μελετᾶν οὖν χρὴ τὰ ποιοῦντα τὴν εὐδαιμονίαν, εἴπερ παρούσης μὲν αὐτῆς πάντα ἔχομεν, ἀπούσης δέ πάντα πράττομεν εἰς τὸ ταύτην ἔχειν.

It’s never too late! In fact, Theophrastus’ Late Learner should be commended for embracing this spirit of adventure even though he’s past the time of life when one would traditionally be learning things. Sometimes, it’s not even a matter of age itself; as we get older, we naturally tend to accumulate more life responsibilities, which means less leisure time for intellectual pursuits.

Although he doesn’t go into it, it sounds like Epicurus is also advocating even for children to start learning some philosophy, which is an interesting idea as well. At any rate, Epicurus notes that by engaging in moral inquiry, we retain a sense of agelessness because such intellectual activity leads to eudaimonia, happiness or, more aptly, prosperity.

It is never too late to get started!

This also made me think of the opening of Book 2 of Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations, a five-part philosophical work composed at Cicero’s country villa in Tusculum. This was a more rural area that was not too far from Rome, yet offered some respite from life in the city. Cicero’s beloved daughter had recently passed away, and the topics covered in the work reflect that, such as Grief, Pain, Emotional Distress, Contempt of Death, and the Benefits of Virtue.

Back to why I thought of this text as being pertinent to our discussion: in the introduction to Book 2, which is about enduring pain, Cicero is addressing his friend Brutus (yes, that one, the co-conspirator of the Julius Caesar assassination). He writes (Latin text here, full English translation here, but the following translation is my own):

In Ennius’ play, Neoptolemus remarks that it is necessary that he study philosophy, but just a bit, since he didn’t find it an appealing idea to become entirely involved with it. But I, Brutus, think that it is necessary for me to be a philosopher; for what better thing could I do, since I’m not especially busy with anything? I don’t want to just philosophize a little bit, like Neoptolemus does. For it is difficult to study anything in philosophy without going down a lot of rabbit holes. You can’t just choose a few things, except if you choose them out of an immense number of topics, and the person who does choose a few things to focus feels he must pursue the remaining topics with the same zeal. But, nevertheless, if you live a busy life or if you are, just like Neoptolemus was doing at that point, serving in the military, studying a few points of philosophy is often very helpful and does bear fruit, even if it is not the same number of fruits that are reaped from studying philosophy in great depth—all the same, even a little philosophy can liberate us to some degree from desire, sickness, or fear.

Neoptolemus quidem apud Ennium “philosophari sibi” ait “necesse esse, sed paucis; nam omnino haud placere”. Ego autem, Brute, necesse mihi quidem esse arbitror philosophari; nam quid possum, praesertim nihil agens, agere melius? sed non paucis, ut ille. Difficile est enim in philosophia pauca esse ei nota cui non sint aut pleraque aut omnia. Nam nec pauca nisi e multis eligi possunt nec, qui pauca perceperit, non idem reliqua eodem studio persequetur. Sed tamen in vita occupata atque, ut Neoptolemi tum erat, militari, pauca ipsa multum saepe prosunt et ferunt fructus, si non tantos quanti ex universa philosophia percipi possunt, tamen eos quibus aliqua ex parte interdum aut cupiditate aut aegritudine aut metu liberemur.

Now, I find these two passages especially interesting to juxtapose because one of them is Epicurean and one of them is Stoic. The Stoics tended to be vehemently anti-Epicurean, and indeed Cicero uses Epicurean philosophy as a counter-example to prove his points later on in Book 2. Despite all this, we’ve found a point of connection, something the two schools agree on: it’s never too late to start practicing philosophy, and one need not become a full-time philosopher to reap the benefits.

Cicero is a bit more bearish on the idea that it’s “never too late,” or rather that it is better to start young and pursue philosophy wholeheartedly as opposed to waiting and then picking and choosing bits of philosophy to study. But even he admits that something is better than nothing!

This is a point that I always agreed with in theory, but am finding to be true in a practical sense as well. Since I finished my PhD, I haven’t had virtually unlimited time to pore over texts like I used to. But I also refuse to give it up; my lifetime of learning has only just begun, not come to an end.

Instead, I’ve picked up what I like to call “microdosing” philosophy—that is, cultivating a life that might not be devoted solely to philosophy (don’t I wish) but fits in intellectual and moral improvement in an approachable way. Some things I’ve been implementing:

Spending 15-20 minutes reading one academic article and stopping whether I finish it or not, instead of feeling like I have to commit to hours of research and dozens of chapters and articles consumed

Choosing works of fiction that make me really think, and reading them slowly

Picking up hobbies that require me to use my brain in some way

Joining interest groups at work to socialize in an intellectually substantial way and/or learn something new

Setting more intentional time for meditation/prayer, even 5 minutes

Working on my Substack has been really helpful for this as I research the topic of my latest essay, but I’ve also started to embrace that practicing or studying philosophy can look different than it does in a traditional academic setting.

For example, I’m rereading Tolkien’s The Hobbit, a perfect autumn read, and the start of a series that is full of philosophical, moral, and religious significance to ponder. The last time I read it, I think I was in high school, or maybe early in college, so it definitely has a whole new world of meaning for me! In other words, I’m choosing to see philosophy even in fictional works; I don’t have to exclusively read Plato or Aristotle or Cicero or Epicurus or any other “full time” philosopher to spend time in moral contemplation.

In addition, I’ve rediscovered my love of playing chess! Chess.com is a frequently visited website now, ha. I find myself looking forward to it more than I do scrolling, which is a huge win. It’s not strictly “philosophical,” but things like chess or a sport or learning a language are very formative for intellectual and also moral improvement. The idea is to keep expanding your horizons. For example, I joined an ecology-themed book club at work, where we read books on sustainability and environmental topics. This is something I know very little about, but have learned so much just from a 45-minute discussion once every month or so.

What I mean to say is it’s perfectly fine, and even beneficial, to dabble in philosophy in whatever way as suits your life. It is never too late, or too early, and everything counts. Most importantly, living a philosophical life means applying its principles in the real world, not studying it 100% of the time.

Would you identify as a “late learner”? What have you learned, or read, or thought about recently? How do you “microdose” philosophy? As always, I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

I hope you enjoyed this week’s essay, and take care until next time.

MKA

This is so good! I love that balance you strike with microdosing- it makes lifelong learning sustainable and accessible while also ensuring you aren’t so consumed by study that you forget to live and apply what you learn! Beautifully written, excited to read more!

I can definitely resonate with the worry that you need a lot of time for this kind of study. That has been a big reason I've stopped doing my own little research and writing my substack, because I'm so rinsed out from work and I feel like I need huge chunks of time.

But maybe you'll inspire me to nib little pieces of it daily!

As for what I currently do...

* Every morning I journal, read some philosophy (usually stoicism, currently Wisdom Takes Work by Ryan Holiday), and copy by hand selected quote from my reading.

* I do crosswords and logic puzzles regularly, almost daily.

* I've been starting to take time to read poetry out loud, without overly focusing on interpreting and understanding. Going through Paradise Lost right now, following my reading of Pullman's His Dark Materials