Love's Little Trinkets: The Material Culture of Romance

You've heard of the Cartier love bracelet, but how about the Tiffany love cup?

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

I hope you’ve all had a good week. Happy February! It’s so much better than January. Things have continued to be somber and unsettled in LA, but life marches on. At UCLA, we’re getting ready for graduate student recruitment. It’s always fun to talk to prospective students and hear about their research and goals for their future doctoral studies. Over at Getty, we have a wonderful new group of winter session Getty Scholars, and it’s been a lot of fun to finally be able to meet them since everyone was able to return to site a week or so ago.

In other news, my committee chair and I decided on a deadline of April 1 to submit a complete draft of my dissertation, which is really exciting. It’s so close to being complete! Finally, I heard back from Classical Quarterly that the proofs for my forthcoming article will be ready soon, which means the article is in its final stages of preparation for publication :) more on that soon! (maybe a mini-series on academic publishing in the humanities?)

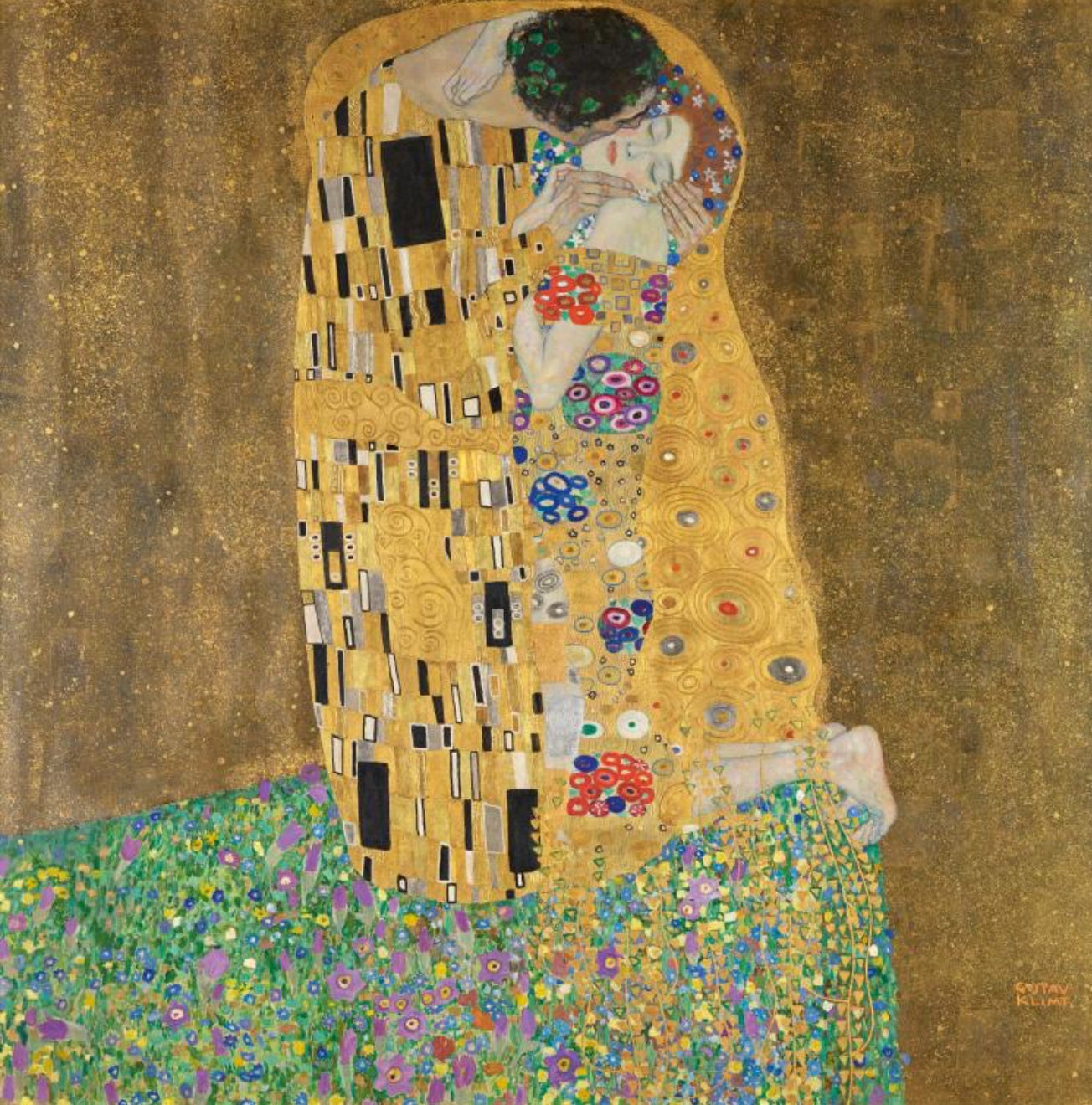

I love February. Especially on the West Coast, it feels like the first whisper of spring is here, especially with Valentine’s Day in the middle of the month adding a little bit of sparkle to the coldest part of the year. So, for this week’s virtual gallery tour, I wanted to dive into the material culture of love. Maybe you've heard of the Cartier love bangle or appreciated the symbolism of a red rose, but what about lesser known objects? Since practically the dawn of time, people have been giving each other material tokens of their affection—the physical manifestation of the intangible and indescribable feeling of love.

First up is this beautiful eighteenth century painting The Love Letter, by Jean Honoré Fragonard:

I love letters. Epistolography (the technical term for letter writing) was a major research area for me for many years, and the Classical Quarterly article I mentioned above is on the collected letters of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius and his close friend, celebrated rhetorician Marcus Cornelius Fronto.

Love letters are particularly enticing, even the fictional variety. My undergraduate honors thesis was about Ovid’s collection of literary love letters from various mythological women to their lovers, like Helen to Paris or Penelope to Odysseus.

The letter is very much about bridging distance and creating the feeling (or illusion?) of presence between two people—even when a letter is really not enough. For example, Ovid has his imagined Penelope write to Odysseus:

Haec tua Penelope lento tibi mittit, Ulixe; nil mihi rescribas attinet: ipse veni!

Your Penelope sends these words to you, Odysseus, you who are slow to come home. I don’t care if you write me back: come back in person!

Somehow Fragonard’s gorgeous painting reminds me of these fictional heroines from classical antiquity. But in context of the painting, we don’t know the identity of her lover, and the golden light in the room gives the scene a more playful than plaintive quality. I don’t know that Fragonard’s heroine is pining for her beau; it is the activity of writing a love letter, of enclosing flowers, that brings her joy. I also love the little dog sitting on the chair with her, showing another kind of loyalty and companionship. Fragonard’s heroine seems to me to be in love with love. The letter contains words that describe feelings, but it is the time and devotion required to actually write and send a letter that ultimately matters.

Maybe from around the same time, maybe a little earlier, another, briefer kind of love writing became popular: the posy ring, a slim band with a line of romantic poetry inscribed on the inside. That’s why it’s called a posy ring, with posy coming from the root for the word “poetry.”

Here’s an example from the British Museum:

It’s hard to see in the photos, but the inside of the ring reads Many are thee starrs I see yet in my eye no starr like thee.

The ubiquity of the posy ring is almost at odds with the kinds of things you see in their inscriptions, which, like the one here, generally describe how a person is always unique and special in the eyes of the person who loves them. Like the love letter, the words can be kept private: nobody can see them while you’re wearing the ring.

Although love is a complex feeling that is difficult to describe, artists and poets across time have been very clever in summing things up in a few sentences. This box in the Met collection caught my eye:

Love me and the world is mine is very poetic, and whoever used this box would be reminded of the sentiment with every use. The line is the title of a song from 1906 by Ernest R. Ball (lyrics by Dave Reed, Jr.), and also the title of a 1928 film. I wonder if the box came first, or if it was inspired by pop culture. If that was the case, then the quotation has an additional layer of meaning: maybe the recipient really liked the song or movie. I’m not sure what the snake element on the side is getting at: snakes are often somewhat ominous in Christian/European contexts, but also symbolize rebirth and transformation. Perhaps we can interpret it as a suggestion that love renews us and leads to transformation on many levels. Or maybe the recipient really liked snakes? Unclear.

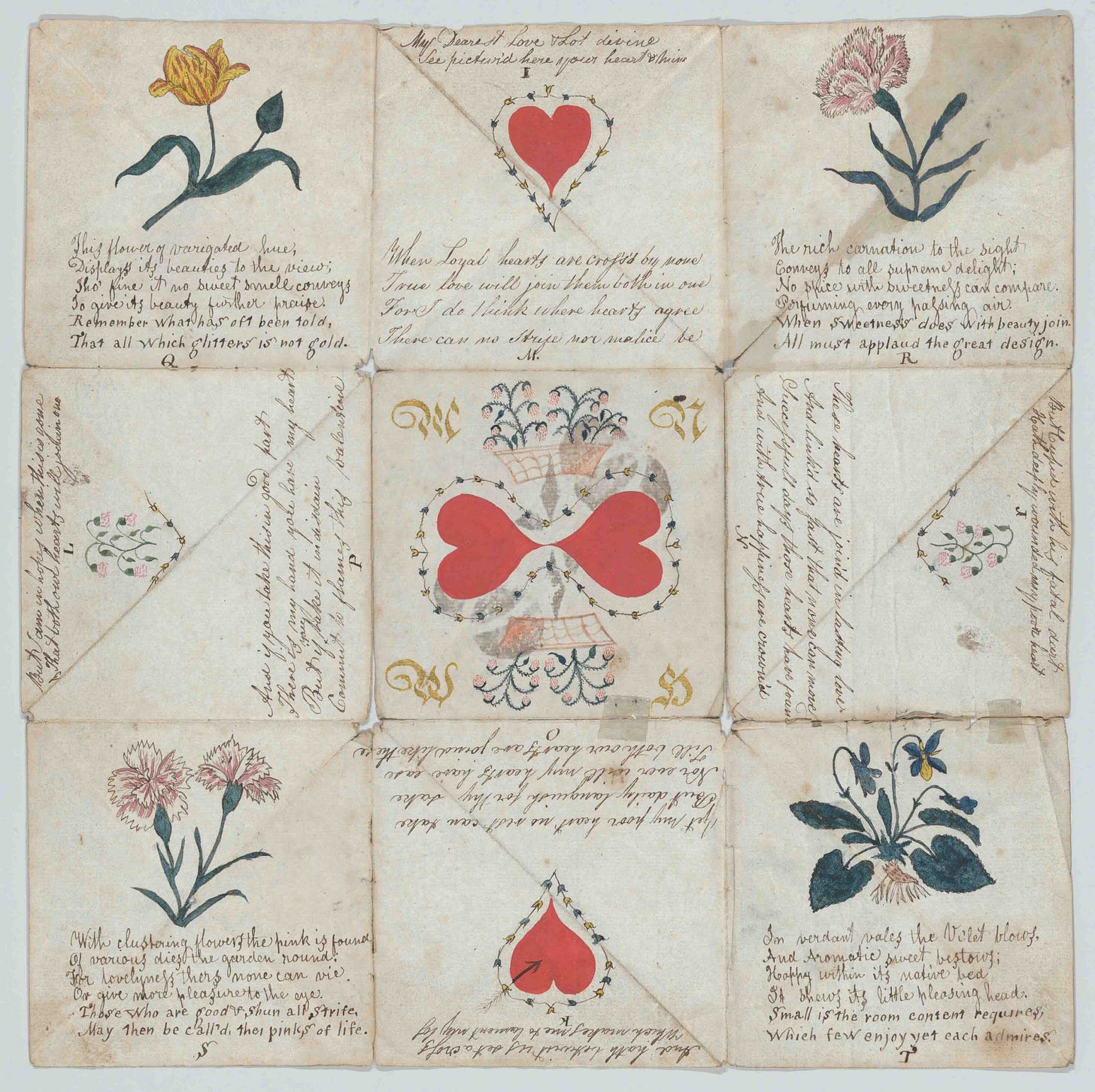

I also recently learned about the “puzzle purse” trend from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. These were elaborately folded pieces of paper into little interlocking envelopes, and used to carry romantic notes or small tokens of affection. Here’s an example:

What strikes me about the material culture of romance is the way in which these material objects allow people to carry on a kind of inside joke or private language/mode of conversation: these small and apparently meaningless pieces of paper are actually so much more than that. They carry with them an impressive range of memories, emotions, and promises made to one another.

If you’re interested in something a bit more grandiose than the humble love letter, puzzle purse,, simple box, or delicate posy ring, maybe the Tiffany “love cup” is more your speed:

These were especially popular in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. There’s nothing really overtly romantic about them, but they were given as romantic gifts or used wedding silverware. Here’s another example:

Usually rendered in sterling silver, these cups sometimes had gold accents or the addition of precious gems. Their motifs tend to take inspiration from the natural world. More broadly, the drinking cup has long been a symbol of unity, affection, and harmony, which are ideal motifs for wedding silver or wedding presents.

Up to this point, all our objects for today have been fairly recent, from the eighteenth-twentieth centuries. The further back you go, it seems, the more artists and poets were interested in the more challenging aspects of love. For example, I love this illumination in a fifteenth-century manuscript, showing a scene from the life of Hercules:

After Hercules was doomed by Hera to go insane and kill his first wife (and their kids), he went through a number of trials, and finally met another girl, Deianira. He thought this was finally his second chance at happiness, but he was wrong. Deianira was sort of insecure, and fell prey to the schemes of the evil centaur Nissus, who told her that she should protect herself against Hercules’ wandering eye by giving him a love potion. Deianira decided to smear the potion on one of Hercules’ shirts. Alas, Nissus secretly had it out for Hercules, and it wasn’t a love potion that he gave Deianira at all: it was poison. The minute Hercules put the shirt on, he began to burn from the inside out. Running through the mountains in agony—the scene we see here—Hercules finally tried to kill himself and end the torment. Thankfully, his father Zeus whisked him away to Mount Olympus, where he became one of the immortal gods and married the goddess Hebe (Youth).

There are plenty of terrible love stories from antiquity, which might have to be a topic saved for another day.

Aside from portraying the long-suffering life of Hercules, the scene might also have a much more allegorical significance about the tribulations of love, a theme that might have resonated with an aristocratic and thus highly educated fifteenth-century audience; this book originally belonged to someone in the court of King Charles VI of France.

“Love as a battle” is a motif that began in antiquity and was especially popular in the Middle Ages. There are numerous objects from that time period depicting an “attack on the castle of love,” an allegorical type-scene showing ladies shooting flowers instead of arrows and some kind of jousting situation going on as well, in addition to scenes of chivalry from Arthurian legend.

Here’s another object with a similar design:

I can imagine the people who used these objects delighting in the idea of love maybe even more than love itself, like Fragonard’s letter-writer above. It’s a nice idea that love might be a difficult battle against the uncontrollable nature of emotion, but the battles are all in good fun. Just like today, “romance” as a trope or a even a “brand” of sorts featured prominently in the popular imagination. Regardless of what actually ends up happening in real life, the rituals and objects of love are always appealing; the material culture of romance gives the whole concept a physical reality in the world that makes our feelings concrete and tangible.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter!

Happy early Valentine’s Day! As we saw in this week’s virtual gallery tour, the material objects of love are many and varied, and we really didn’t even scratch the surface. Obviously overconsumption is an important conversation, but, from antiquity to the present, physical tokens of affection have always had their place in popular culture.

Take care until next time.

MKA