Lead into Gold: Notes on Alchemy

Alchemy: a discipline at the nexus of philosophy, science and magic. Or was it just the ultimate scam?

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

One of the few books I had to read in middle school that I actually ended up wanting to read again later in life was Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist. Even then, I found the combination of the classic “hero’s journey” with mysticism and philosophy endlessly compelling. Once I began working on my PhD dissertation on philosophy and rhetoric in the ancient world, I became interested in alchemy in a more academic sense, because alchemy as a (quasi) scientific discipline encompasses both philosophy and rhetoric in addition to astrology, astronomy, religious ritual, chemistry, biology, and other fields, as well as general occultism. In other words, there’s no real “single” practice or definition of alchemy. In antiquity, it was referred to as a τέχνη (technē), or “art,” something that took practice, dedication, and skill to master.

We might think of alchemy as primarily dealing with the cliché fool’s errand of trying to turn lead into gold, but it was so more than that—nor was it limited to the Western intellectual tradition. There are attestations of alchemists in the Greco-Roman world, the Islamic world, China, India, and elsewhere. Alchemists were interested in changing lower value materials into higher value ones, as well as discovering an elixir for immortality and immunity from illnesses. It started in the first few centuries CE, began to boom in the Medieval period, and had a real heyday in the early modern period. By the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, people were more suspicious about it being a scam, but there was still interest in it.

There’s a lot of great digital content on manuscripts as digitization of archival materials becomes more widespread. For example, I was looking at this edition of the so-called “Rosary of the philosophers” from the Manly Palmer Hall collection of manuscripts at the Getty Research Institute. This was an alchemical treatise from the sixteenth century. The word “rosary” refers to a rose garden, which was used as a metaphor or synonym for the word “anthology” (anthos = flower). So this would have been like a compilation of sayings.

But let’s turn to the art for today. We’ll take a look at how alchemists and alchemy are reflected in art and material culture as both an aspirational practice to bring the soul closer to the numinous divine and also as a pseudo-scientific discipline that belonged to con artists and those with delusions of grandeur. It’s the complex relationship between prestige and disrepute when it comes to alchemy that I find so fascinating.

The alchemist’s laboratory

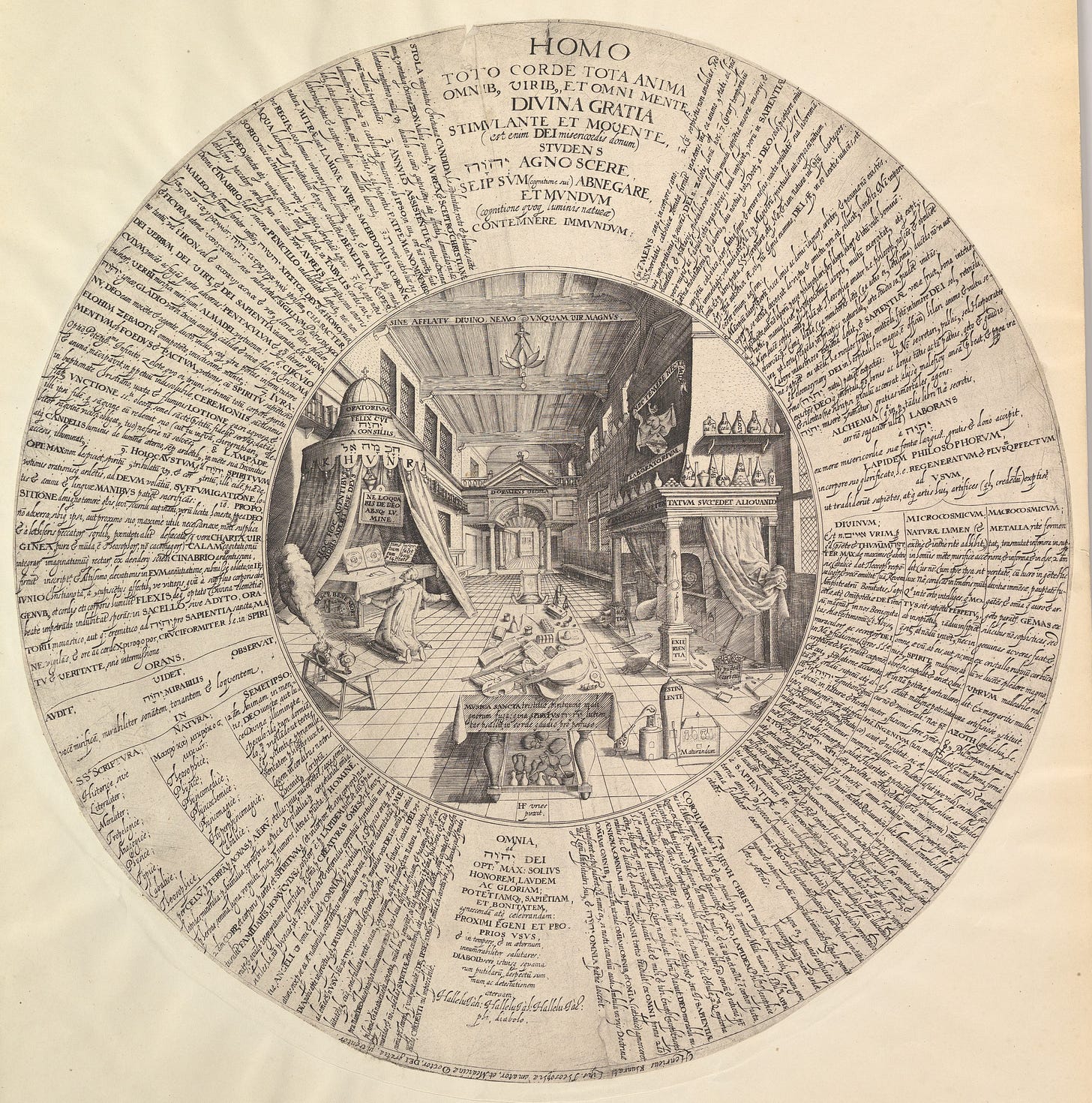

Alchemists are the ultimate multi-hyphenates: scientist, philosopher, inventor, and magician all in one. I love this engraving that shows off the grandiose nature of alchemical innovation:

Written in Latin, the top part of the wheel says “Man: with all his heart and all his soul, with all his strength and all his mind, with the favor of the divine urging him on and moving him…” and goes on to talk about his desire to discern in greater depth various mystical/spiritual subjects. Around the wheel, it’s fairly easy to pick out words like sapientia (wisdom) and mirabilis (miraculous), as well as “Jesus Christ,” “God,” and “Hallelujah,” highlighting how alchemy in the West was closely intertwined with Christianity. Of course, practitioners in other parts of the world were equally entrenched in their own cultural contexts, and alchemy dovetailed well with basically every religion there was.

The laboratory depicted in the center of the wheel is fascinating. It looks palatial, and the Neo-classical architecture speaks to the fact that alchemy had, even at this point, been practiced for centuries. The room has a pile of musical instruments heaped up in the middle of the room, possibly suggesting the importance of sound or vibration in alchemical work. There’s some kind of vessel emitting a puff of smoke in the lower left corner, and a man—the alchemist—kneels down before an altar-type canopy. One of the things written on the canopy says Hoc, hoc agentibus nobis adeat ipse Deus, “May God himself be at our side as we do this, this,” presumably referring to the practice of alchemy. The alchemist himself seems to be in the throes of rapture as he gains access to the arcane knowledge of the divine.

Christianity was not the only religion to embrace alchemy. In China, Daoism embraced a kind of spiritual alchemy that sought to bring individual souls closer to the divine. This hand scroll was created by Qian Xuan in the thirteenth century in the wake of the collapse of the Song dynasty. Here, the artist looks back to the glory days of old by portraying a tranquil scene that features legendary cultural figure Wang Xizhi, who lived in the fourth century and was famous for practicing Daoist alchemy:

The alchemist-philosopher-master calligrapher-politician-general-poet (remember what I said about alchemists being the ultimate multi-hyphenates) stands in a gazebo, overlooking a serene lake with geese. Wang’s pursuit of Daoist ideals involved an emphasis on spiritual improvement and purification of the soul, and his portrayal as being wholly immersed in the beauty of nature suggests that he has achieved this harmonious state of being. Alchemy isn’t so much about turning lead into gold or achieving dramatic scientific innovations; the transformation is an internal one, but its effects are equally as striking when we see Wang from afar and aspire to be like him. His attainment of alchemical transformation is somehow more intimate than that of the nameless alchemist in the laboratory depicted above.

Not every alchemist, however, was someone to emulate. Indeed, other artists portrayed alchemists in a much more down-to-earth manner, as we can see, for example, in this painting by Cornelis Bega:

By the seventeenth century, as I noted above, alchemists were starting to get a bad reputation for being frauds. This alchemist here looks very unkempt, and the room is a mess. Far from being a palace, it’s a dark little hovel. Actually, this is kind of the way ancient sources stereotype the philosopher figure: unkempt and unshaven, living in a state of poverty in order to best carry out the hard work of philosophizing. So it is with our alchemist here. Yet even though everyone thinks he’s a fool, he remains devoted to his craft, and there’s something admirable about that. The large quantity of pots around him, plus his generally ungroomed appearance, reminds me of a Cynic philosopher from antiquity. The Cynics famously espoused poverty, and one of the most famous of them, Diogenes of Sinope, allegedly lived on the streets in a broken pot and yelled at passersby in an attempt to get them to think critically about their own lives.

But there’s no evangelism here from this alchemist: his expression of concentration doesn’t invite the viewer to admire him or even to participate in what he’s doing, and unlike the grand laboratory from above, we can’t even really see what he’s working on. It seems unlikely that God Himself, ipse Deus, is looking in on our poor alchemist at all. The alchemist doesn’t care. Maybe we should pity him for trying over and over to achieve something to no end—or maybe we should admire his tenacity. He seems to have found a tranquility that looks very different to that of, say, Wang Xizhi, but maybe there are more similarities between the two than we might assume.

Alchemical objects

After seeing a few depictions of alchemists, you might be wondering if they were basically just made up and not actually real people. Well, there are a number of artifacts from various points in history that provide some insight into how alchemy was practiced in the real world, not just depicted in art.

For example, this fifteenth-century ring looks very average, but there’s more to it than meets the eye:

It’s inscribed with the following letters: TE BA LG UT GU TD AN I+ So far, it’s not entirely clear what each unit means, but, as the British Museum notes, a manuscript on alchemy states that this was a charm to give the wearer protection against illness.

It seems that the ring would be imbued with magic, like an amulet (amulets have a long historical record going back to antiquity and possibly even pre-history). But I can’t help but wonder if the person who owned this ring actually believed that it would work. Sure, alchemy was still a prestigious discipline in the fifteenth century, which means that people still believed it had some legitimacy, but I wonder if the owner wore this ring faithfully for years on end—and, if they did, whether or not they evaded illness successfully. There’s no way to know! But I can imagine these types of objects were probably fairly popular: you can get the benefits of alchemy without being an alchemist yourself.

In other instances, the practice of alchemy doesn’t actually yield any of the discipline’s stated goals, and yet alchemy still yielded something beautiful and interesting, like this statuette:

In Europe, there was an intense desire to be able to recreate the beautiful porcelain objects that East Asian cultures had been producing for time immemorial, but it wasn’t until the early eighteenth century that the Germans managed to crack the code.

Johann Friedrich Böttger was credited with coming up with the formula to make porcelain in Europe, but what I find most interesting about him is that he had an avid interest in alchemy even when formal pursuit of the discipline had already been waning for decades. He really believed that one day he would be able to turn lead into gold, and kept making substances that could withstand higher and higher temperatures, until one day he succeeded not in making gold but in producing porcelain. The subtle gilding on the object seems like an oblique, or probably unintentional, reference to this turn of events. Over time, the Meissen workshop (among others) turned to making copies of Chinese porcelain figures, which had sparked their interest in porcelain in the first place.

The object itself obviously pales in comparison to a genuine porcelain figure from China, but it does go to show how alchemy influenced other fields. Shoot for the moon and miss, &etc.

The true pursuit of knowledge

In the above example, failed alchemy still led to an interesting discovery (even if Böttinger and others were centuries late to the porcelain game). Some people, however, didn’t think too highly of alchemy, even at its best.

For example, this sixteenth century needlepoint is called The Garden of False Learning:

The scene is based on the so-called Table of Cebes, which is a spurious text once believed to be the work of one of Socrates’ students. It describes the lofty pursuit of attaining true happiness and wisdom. Obviously, alchemy wasn’t part of this vision. But alchemy isn’t the only one to get dragged: also alluded to as detrimental pursuits in the Garden of False Learning are rhetoric, debate, and astrology, as well as widely admired disciplines such as geometry, music, geography, and (gasp!) philosophy. Here, False Learning is personified as a beautiful woman, and the courtiers around her are spending way too much time focusing on these academic disciplines when they could be pursuing true happiness. It’s interesting to me that true wisdom and happiness come by moving away from rigid categories or fields and focusing on an experience that is more expansive than any one pursuit can provide. This idea makes me think back to Wang Xizhi, in a state of tranquility as he takes in nature’s beauty; he is not obsessing over poetry or philosophy or religion. He is simply present in the moment, perhaps the true catalyst for spiritual transformation, alchemy’s highest goal.

Ironically, the process is, at its heart, alchemical: we have to take everything we learn and consume and transmute it into something more than the sum of its parts. Even philosophy, that most lofty of arts, can end up being a hindrance if we focus too much on it—and yet all these sycophants of False Learning end up being helpful in the end, as long we don’t rely overmuch on them. Instead, success lies in one’s ability to see the unseeable, to move beyond the knowable and thus into a more sublime experience.

Thank you for reading this week’s edition of Reading Art!

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter. As always, I would love to hear your thoughts on alchemy and the many intersections between magic and science throughout history. Take care until next time.

MKA