Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

The end of the year is both a flurry of activity and a time to pause and spend time with family. In this week’s virtual tour, we’ll look at portrayals of winter and winter holidays from the Medieval and early modern periods. I’m on an illuminated manuscript kick again, so we’ll take a closer look at those as well. By the last couple weeks of December, I’m ready for all the cozy vibes. There’s no such thing as a white Christmas in LA, so the best we can do here is look at some art.

To start us off for today, this drawing by Gerrit Battem captures the balance between the harshness of the snowy months with the levity of the holiday season:

The landscape is somewhat washed out, and the bare trees really stand out against the faint blue of the sky. Battem, like other Dutch painters of his era, were interested in scenes of ordinary people in daily life, but with an added touch of fun or, as Getty suggests (see the link in the caption to the collection entry), whimsy, an excellent word to describe this scene. In the distance, some figures are skating on the titular frozen canal, and elsewhere in the scene people group together. There’s nothing that particularly screams “holiday” about the drawing, but it captures the sense of community, right down to the running dog at the bottom center, who seems to hurry to join one of the groups.

You might think that people would be inside one of the many buildings to ward off the cold, but instead they’re outside. Not only does the frosty weather not deter them, it actually makes things more fun, since the canal becomes a skating rink and a community gathering place.

Saturnalia: The Holiday Season in Ancient Rome

Indeed, the “point” of the winter holiday season has generally been to make a cold and dark time of year a little bit more fun. There are a number of winter holidays that were celebrated by various cultures in antiquity, but for today I want to focus on the Roman festival of Saturnalia, which, as the name suggests, celebrates the god Saturn. Saturn was often equated to the ancient Greek Titan Cronos, the father of Zeus, god of the sky and king of all the gods. According to many traditions, Saturn/Cronos did not want his children to grow up to be more powerful than all of them, so he ate them as soon as they were born. Zeus eventually forced his father to vomit up him and all his siblings—the other gods—and then they promptly overthrew their father in order to ascend to the throne.

There’s a little bit of cognitive dissonance; on the one hand, he was Zeus’ great adversary, but on the other hand his reign was known as the Golden Age, a time of great prosperity—during this time, food just grew spontaneously, so humans didn’t have to work. As a result, Saturn was often recognized as a god of prosperity and abundance. Let’s just forget about the cannibalism.

Around the winter solstice, the Romans celebrated Saturnalia, a time when many social customs were reversed. For example, according to some sources, the enslaved were often given a rest from labor while the slaveowners worked. Other sources say that gifts were exchanged and it was permissible to do things that were ordinarily illegal, such as gambling in public places. Some households would even appoint a “Lord” of Saturnalia, who would command the others to do silly dares like shouting something embarrassing or insulting. People would play games and wear clothing normally reserved for dinner parties. In addition, everyone would wear a special hat usually reserved for formerly enslaved people who were freed (known as freedmen) to represent freedom and abundance. Saturn represented the waning of the year, aka death, but also the promise of reinvigoration in the new year.

Antoine-François Callet’s “Saturnalia” captures the festive feel of the season:

As you can see, people are dressed in light, bright colors—I don’t see any freedmen’s caps, but just imagine them—and are engaged in feasting with the whole family, including children (bottom left) and pets (bottom right). In the bottom center of the scene, you can see a pair of manacles with chains laying open on the floor, symbolizing the fact that the enslaved were given a temporary freedom and the ordinary activities and customs of Roman life were abandoned. In the background, you can see people running around and maybe dancing, the only hint of dreariness coming from the snippet of grey sky visible at the top of the scene. Despite the grey sky, Saturn’s golden light falls upon the main figures, illuminating them and also representing the prosperity and joyfulness they get to experience during this festival.

The green garlands around the columns remind me of Christmas decor, and indeed the artist was probably inspired by the Christmas celebrations of his time. That’s where we’ll turn next.

From polytheism to monotheism: Christmas traditions old and new

While Christmas marks a distinct cultural and religious event—the birth of Jesus—many of the traditions from polytheistic cultures became folded into Christmas celebrations. For example, gift-giving and charity characterize a number of end-of-year holidays.

In the Medieval and early modern periods, artists found much inspiration in scenes of Jesus’ life, and especially Nativity scenes. For example, Andrea Mantegna’s mid-fifteenth century painting “The Adoration of the Shepherds” depicts a popular theme:

Like Battem’s winter scene with ordinary people, this painting also features non-aristocratic characters, as the humble shepherds have the chance to meet Jesus. I love how their relatability is contrasted with Mary’s otherworldliness—if you look closely, her blue cloak turns into a sort of blue mist, with little winged cherubs (baby angels?) coming out of it in shades of red and gold.

As with both works of art we looked at prior, winter is a time of paradox between dark and light, emptiness and joy. In this scene, as with the Saturnalia scene, the barrier between mortal and immortal becomes blurred. In some instances, like with Mary’s little cherubs and mysterious blue cloak, it’s more clear. In others, it’s less apparent. For example, I’m not sure why Joseph looks so depressed over there on the left. Maybe because it’s not his kid? Unclear. But his yellow garment really draws the eye, and the part that wraps over his head almost looks like a halo, which would point to his status as a saint. Yet neither Mary nor little Jesus get anything halo-like over their heads. Very interesting. If you squint up at the upper right corner, you can see the scene of the shepherds being visited by angels, announcing Jesus’ birth to them. The angels themselves are not very distinct, despite their exalted status. Perhaps there’s a similar feeling as with Saturnalia: this is a time when usual roles might be reversed. A normal human woman becomes the mother of the embodied God; some lowly shepherds get to be among the first to meet him in the flesh.

A rendition like Mantegna’s is particularly striking when juxtaposed with other more opulent examples, such as Giotto di Bondone’s centuries-earlier rendition of the adoration of the Magi:

The gilded halos around Jesus, Mary, and Joseph are a mark of the stylistic preferences of the time, but they also present quite a different relationship between human and divine. There’s a clear hierarchy here: the halos of the holy family and the crowns of the Magi are both done in gold, but the halos overshadow them somehow.

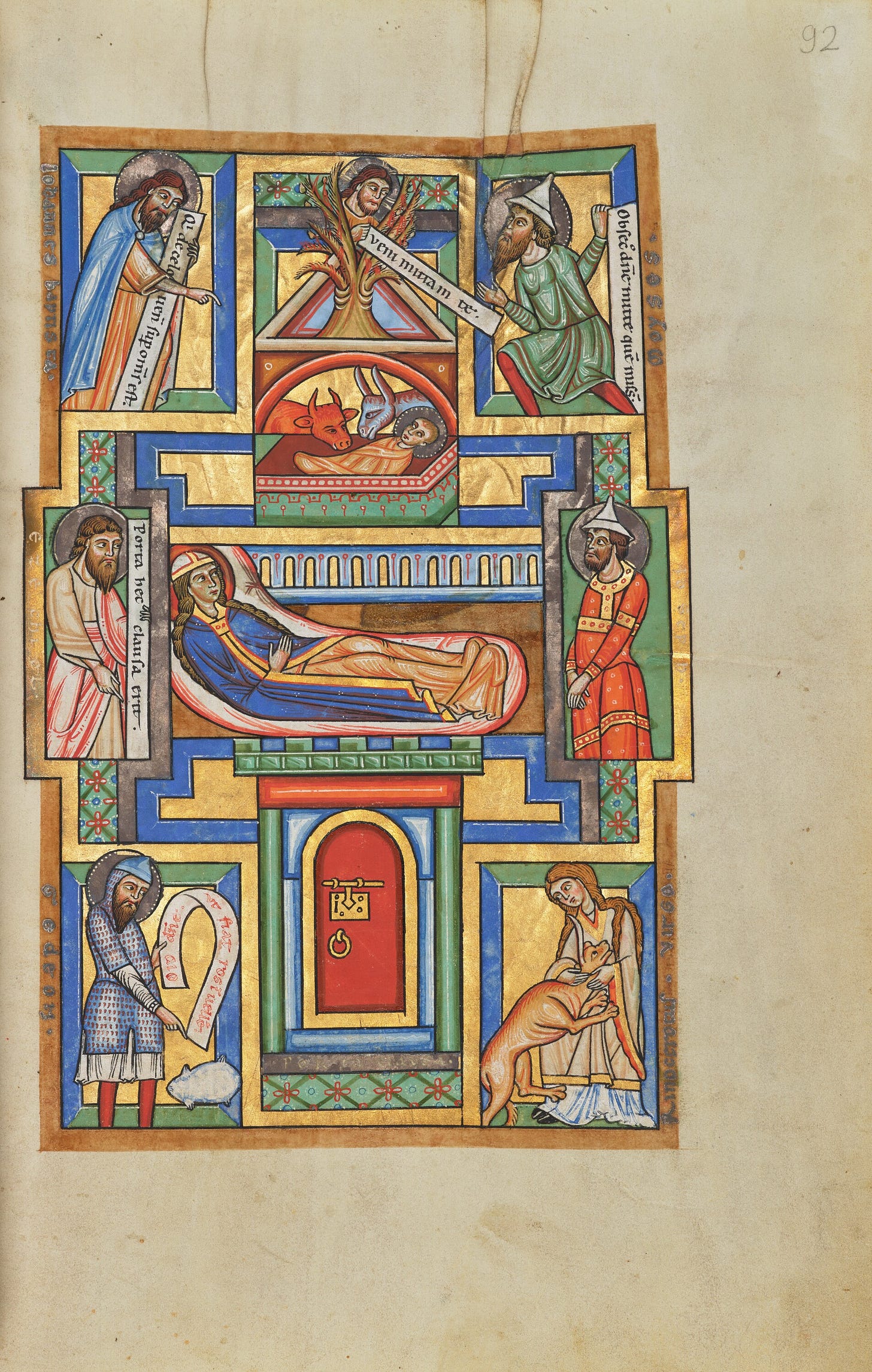

As I mentioned at the start, illuminated manuscripts have really captured my interest at the moment, and there are plenty when it comes to the Christmas story. Here’s a beautiful example from the Stammheim Missal (a missal has prayers used in a Catholic Mass, for different times of the year. In this case, the Old Testament passages inscribed here would be used on Christmas Day):

I love the bright primary colors used here. Not uncommon for illuminated manuscripts by any means, but somehow it suits the Christmas Day context. So much of what makes a holiday a holiday is the performance of the same rituals year after year, whether that’s a literal religious gathering or something like exchanging gifts. Cultural memory is linked with the repetition of these activities; festive spirit is not just something we feel, but something we do.

Scenes of the Hanukkah story

Let’s continue with our focus on illuminated manuscripts. As it happens, Hanukkah is this week as well (and Saturnalia might technically extend a bit into this week as well, starting around December 17 and lasting for a week).

As with Christmas, in the case of Hanukkah it’s also more typical that Medieval artists would illustrate the story behind the holiday as opposed to scenes of people celebrating the holiday in later eras. Here’s a vibrant example of a scene of the triumphant Maccabees retaking the temple:

I love this one because the whole scene is actually decoration for a single letter, A, that would begin a paragraph of text. In an illuminated manuscript, then, text and image work closely together. Here, the artist has chosen to render the second-century BCE Maccabees as medieval knights, bringing the scene into his present day. During this period, Christians took inspiration from the Maccabees when it came to the Crusades—not a very pleasant circumstance, but that’s the historical context. In this case, though, I prefer to think about the meaningfulness of Hanukkah—a word that means dedication, as in the dedication the temple after the attempted Hellenization by the Seleucid Greeks—as a time of hope, faith, and even abundance during a challenging period.

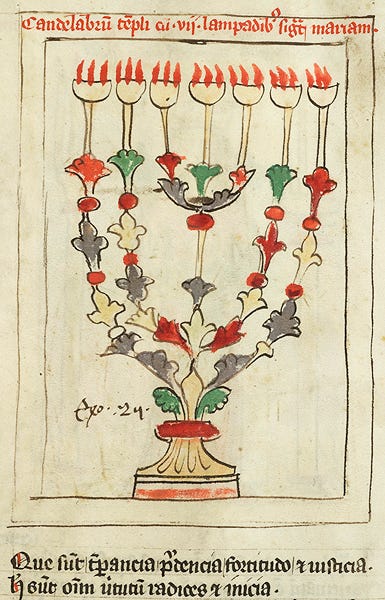

Here’s what is perhaps a more expressly Hanukkah-themed illustration from a manuscript, from roughly the same time period:

The flames of the candelabrum are both stylized and somehow capture the warmth of the light, now a symbol of faith and triumph over adversity.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter!

To conclude, the scenes we’ve looked at today convey the many ways in which different time periods and cultures have marked important holidays. From antiquity to the present, December has been a time of celebration, joy, and unity. I hope that you have a very happy holiday season! Take care until next time.

MKA