Everyday Magic: A Closer Look at Amulets

These small yet potent objects embody the hopes and aspirations of their creators, wearers, and owners

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

When you think of the Greeks and Romans, one of the first things you might think about are the many famous and infamous gods in their respective pantheons. Religious observance and ritual gave life in the ancient world a certain rhythm and structure. But there was another side to divine worship in antiquity as well: in addition to religion, the occult, the magical and the metaphysical also played an important role as well.

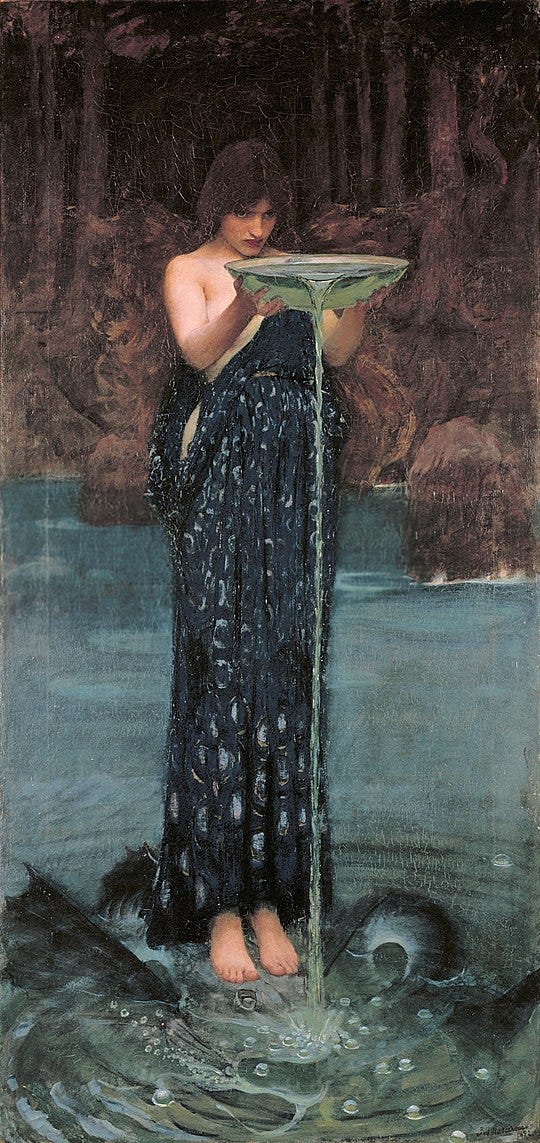

You might think of someone like the sorceress Circe as an example of an Ancient Greek magic user, the granddaughter of Helios, the sun, and a relative of Medea, another famous sorceress from classical mythology. These powerful women used the talents given to them by their divine lineage to get what they wanted: love, power, or just the right to live as they pleased.

But for today I want to turn to less flashy, less well-known magic users from antiquity, and the objects they used to make things happen. In today’s virtual gallery tour, we’re going to look at several of these “everyday” magical objects, mostly from antiquity.

A common practice among many cultures of the world is to create spells and amulets designed to protect the spell-caster or to enact something on another person, sometimes good and sometimes bad. These spells sometimes invoke a specific deity or deities, and sometimes they do not. They have similarities with prayers, in that they state a wish for something to happen, but they were not generally part of religious worship; they fall under the category of private or “everyday” magic, something individuals would pursue on their own depending on their own personal desires.

In antiquity, some cultures were associated with the practice of magic, such as the Zoroastrians and the Chaldeans. But magic appears in a variety of ancient religions and cultures, including the Greeks, Romans, Egyptians, Jews, and others. It coexists with organized religion, but its rules were not as clearly defined. Or, rather, they were more clearly defined: magic was supposed to operate according to the wishes of the magician in question. One could inscribe an amulet or tablet with the spell themselves, or seek out a practitioner to help them.

Our first example isn’t much to look at, but it’s a good example of an ancient Roman curse tablet (Latin defixio) from the third century, which is exactly what it sounds like:

The inscription lays out a curse against a certain Demetrius and some other people. The practice was fairly simple: you would write out a curse against your enemies, and then bury it in the earth. The venom of the ill intent toward the people named in the curse would then do the work.

We see traces of magic appear in literature too. For example, Apuleius’ Golden Ass, an ancient Roman novel, describes the adventures of a man named Lucius who becomes the victim of a witch and is turned into the titular ass, forced to roam in animal form until he can break the spell. To cite another example, Ovid’s Ibis is a long poem that details the poet’s enmity with a person he calls by the pseudonym Ibis, who seems to have been partly responsible for Ovid’s exile and other perceived slights. In the text, Ovid threatens Ibis with a number of unpleasant things, such as torture, and also promises to haunt him after Ovid has died.

Magic, however, was not always vengeful. In many cases, magic was meant to have a healing and/or protective function, and there was a market for magical amulets imbued with the power to benefit the wearer in some tangible way.

One of my favorite examples is this Roman amulet (slightly earlier than the last example, 150-200 CE) featuring the god Kronos, who was the father of Jupiter/Zeus, king of the sky and the pantheon. Kronos was associated with hard work, abundance, and prosperity, among other things.

Kronos has some interesting features here. He’s holding an animal that could be a crocodile or a gazelle, in addition to a sword. A solar disc hangs above his head, revealing Egyptian influence. In the background is an eight-pointed star and a crescent moon. The inscription reads as follows: “Iaō, Sabaōth, and Adōnai, the three great (ones).” As Kotansky (1980) has suggested, Kronos was often invoked for granting wishes. In this case, the wish is not made entirely clear, but it probably was an amulet for protection and prosperity. The three names listed are frequently seen in Greco-Egyptian spells and mean “Lord,” titles to address the god by when he inevitably appeared to grant the wearer the desired blessing.

In other cases, the amulet does state a specific wish, such as this one here from a similar time period as the previous examples:

The agate stone of the amulet is carved with the name Ablanathanalba, which is seen fairly frequently in spells from this period. It also has the words “Deliver Gaia from fever.”

There were a number of healing practices available in antiquity aside from actual medical intervention. One is wearing an amulet like this; another involved going to sleep overnight at the temple of Asclepius, the god of healing. These kinds of practices required that the patient believe in the unseen, in the power of the divine to do what the human was unable to do. Certainly, there are many miraculous stories from antiquity of people being cured of everything from blindness to the plague. But I imagine in many cases as well that the prayer or wish did not come true; all the same, there was a persistent belief that such magical remedies might be effective.

The practice of magic also thrived in ancient Egypt, where amulets and spell tablets were also very popular.

One of my favorite examples is this one. This one is from much earlier than the previous examples (3500-3300 BCE), and amulets were far less common in those times, which makes this piece stand out even more:

The piece features an elephant head with extremely round eyes and curving tusks. Since elephants are large, strong, and in many ways aggressive creatures, they would be good subjects for amulets that could perhaps promise to endow the wearer with that same strength and resilience (or, perhaps, the elephants’ wisdom and memory).

Oftentimes, amulets feature specific gods or goddesses, and I love how this one features an animal. Of course, animals were greatly revered in Egypt, and very often linked with gods. The elephant is curious, though, as there are no known elephants gods. In Greco-Roman times, they were associated with Seth, the god of storms and chaos. But in the Predynastic period, it’s not entirely clear what the cultural significance of the elephant was for Egypt (unlike in the case of, say, Nubia and India). One possible interpretation is that during this period nature was already strongly connected with divinity and magical power, whether or not the animal in question was specifically linked with a god or goddess.

Here’s a more typical type of Egyptian amulet (c. 1400 BCE), also in the Met collection:

This type of piece is known as a heart scarab. The inscription suggests that it belonged to a woman named Hatnefer, who was clearly of high social status owing to the gold and fine level of detail, and the amulet’s inscription includes a passage from the Book of the Dead, a compilation of Egyptian spells for safe passage to the afterlife.

In the Egyptian world—as in the Greco-Roman world—the heart was the center of reason, thought, and memory, and therefore it played an important role in the transition to the afterlife: as the ritual goes, the heart or soul had to be weighed against a feather in order to pass on. Amulets such as these would be intended to secure a positive experience for the deceased; if the heart was not found to be light enough, it would be devoured by Ammit the Devourer, a goddess with a crocodile’s head and a lion’s body.

In other instances, Egyptian amulets for the dead were intended for healing the deceased. This type is fairly typical. Instead of depicting a god or animal, it simply has two fingers:

The intention was that this amulet would heal wounds of the dead from mummification, as the Egyptians believed that you more or less went to the afterlife in the same form you were in life. In this way, we can see certain parallels with Greco-Roman amulets, although the former generally did not cast spells for the deceased, only for the living. For the Greeks and Romans, life was very much in the here-and-now, and the Underworld was not an extremely pleasant place; for the Egyptians, conversely, the afterlife was of utmost importance and an even better experience than the mortal world. In this way, you can see how magic was very significant for these three cultures, but its use was tailored to their specific beliefs about the nature of reality.

Finally, I wanted to jump forward in time and across the globe and look at a Tlingit amulet from the Pacific Northwest (Alaska and Canada, specifically), created in the early-mid nineteenth century:

The amulet is in the shape of a whale with a bird of prey on its back, and the colored stones are abalone. The Tlingit, like many indigenous peoples, revered the inherent sanctity of nature. In this case, the raptor might symbolize strength, while invoking the whale might signify a desire to cultivate wisdom. The custom of this culture was for a shaman to carry out rituals for the good of his community and also to enter a heightened state of consciousness so that he could divine what would the best course of action would be to ensure the prosperity of the group.

In other cases, amulets such as these were given to people in need of healing, creating a sort of potent energetic connection between healer and patient. Amulets would therefore be worn both by spiritual/religious authorities and by private individuals.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter!

In looking at these examples of amulets and other magical objects, I found myself inspired by the open-mindedness of their makers and wearers to embrace the metaphysical. I also find it fascinating that there was a sort of occult spirituality thriving alongside the formal state religion(s) of these cultures.

Take care until next time.

MKA

This was so insightful. I’m absolutely looking forward to more of this!