Capturing Childhood: How to Make The Mundane into the Wondrous, According to Nineteenth Century Art

These scenes depict everyday children in the process of creating their own fun, bridging the gap between adult cares and a timeless sense of joy

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

Today is the first day of UCLA’s spring quarter, which always seems to have the most festive feel of the three terms. With summer break on the horizon a mere eleven weeks away and the winter weather yielding to warmer temperatures, it just feels more fun.

Over at Getty, I’m currently working on a project that takes a deep dive into the history of the Scholars Program, which has hosted visiting researchers at Getty every year since 1985. The visiting scholars pursue a wide variety of fascinating projects in art history and related disciplines. After looking at some old photographs of past scholars from the 80s and 90s, I noticed a number of them feature the scholars’ families, and particularly their children, whose unselfconscious willingness to embrace every moment makes these photos particularly meaningful. It’s so funny to think that these kids would be in their thirties or maybe even their forties now.

This journey back into the archives inspired the theme for this week’s virtual gallery tour: children in art. For many of us, this topic might immediately call to mind, for instance, the many examples of fertility/mother goddesses depicted with children from antiquity, or Madonna and Christ Child images from later on in history. These divine and/or religious scenes of childhood are gorgeous and well worth their own newsletter. But for today I wanted to focus on the realm of the human, the everyday child captured in a moment of play.

First up is one of my favorite works by American Impressionist painter Mary Cassatt from 1884, Children Playing on the Beach:

Scholars suggest that the scene was inspired by the untimely death of Cassatt’s sister, Lydia, in the early 1880s. Here, I love the juxtaposition of microcosm/macrocosm: the viewer first takes in the coastal scene as a whole, with the suggestion of sand dunes and white boats on the water that pick up on the white of the girls’ pinafores.

Then we see that the girls are not observing nature’s majestic splendor on the grand scale, but are wholly focused on their own activities. The girl on the left is shoveling sand into a small bucket, maybe preparing to make a sandcastle. It’s harder to see what the girl on the right is doing, and her hat obscures her face—if indeed this is an homage to her sister, possibly the pose gestures at that loss—but we can see that she too has a bucket. Instead of scooping sand in, though, she’s looking down at it. Is it actually a bucket at all? Something about it has a seashell or abalone-like shape to it, although I’m fairly sure it is a bucket. Nevertheless, the raw and indeed impressionistic nature of the scene highlights their devoted concentration on making a simple activity like sitting on the beach into play, which transforms the mundane into the fun and, from there, into the sublime.

I can’t help but think of Cassatt engaged in the play-like work (work-like play?) of creating such a painting, so adeptly capturing childhood’s joy, which exists separately from adult concerns. Although the scene can be read as a focalization of these adult concerns, such as the shock and grief of losing a sibling, it seems to me that these two children on the beach exist apart from such experiences. For them, there is only the meditative state of playing together on the sand.

Staying in the nineteenth century, let’s look at Hugues Merle’s Children Playing in a Park, also in the National Gallery:

Merle was an acclaimed French painter known for his focus on portraits and genre scenes of everyday life. Although he’s pre-Impressionist, his works have a similarly ethereal quality to them, an interplay between blur and sharp focus that highlights the emotionality of the scene.

Unlike Cassatt’s work above, we don’t actually see much of the surroundings, which are kept in shadow. There’s really only a suggestion of a park, with some hint of orange flowers at the edges and lots of trees. It almost looks more like they’re in the middle of the forest, a more wild place than a manicured park, seeming to emphasize further that children exist in a world of their own, a world that is governed less by rules and more by joy.

In some ways, the children remind me of cherubs, and the rightmost girl’s gauzy light garment sweeps around her in a winglike way, but these children are wholly of the everyday: unlike divine children, they wear clothes and, in particular, shoes (at least, I’ve never seen a cherub wearing shoes). But the children’s unpracticed ability to make a game out of anything—that is, to create fun out of nothing—seems to make them closer to the divine, maybe an important model for adult viewers. Merle was, after all, fond of moralizing scenes.

Indeed, children are often a natural choice for artists wanting to impart some kind of moral lesson to their viewers. For example, here’s a work by William Mulready, another genre painter of the nineteenth century. Born in Ireland, Mulready was based in London for most of his career, and quickly became renowned for scenes of pastoral living and for his illustrations of children’s books.

Let’s look at his Teaching a Child:

This one is interesting. A child appears with a little dog and two women, who are maybe a mother and an aunt, or older sisters, or simply caregivers. The child reaches out his hand to some figures on the right, who seem to be experiencing difficulties. In fact, this was commissioned by Thomas Baring, who asked Mulready to show a scene of a child helping some “destitute Indian sailors,” as the Louvre describes the scene. So, who is teaching the child? Are the women in the scene telling the child to help? No—it seems rather that the child has a natural sense of compassion. In other words, the title refers to the positive outcome of teaching children well: they become, to put it bluntly, better people who go on to benefit society.

But, while it seems true, somehow I’m not completely settled on this interpretation, either. The women are not looking at the sailors, and the gesture of the woman on the left seems almost surprised. She touches a hand to her face, and her other hand seems ready to hold the child back. It seems that maybe this scene is more about children teaching adults than it is about adults teaching children.

As we discussed above with the Cassatt painting, sometimes scenes of children at play offer the artist a way to commemorate a loss; instead of a sterile portrait, sometimes the best memorial is one that is full of motion and innocent happiness.

One such example is Ambrose Andrews’ The Children of Nathan Starr from 1835:

Andrews painted this to commemorate the death of the family’s youngest son, Edward, who is generally thought to be the child at the center, surrounded by his three siblings and his mother.

What strikes me about this is that you would really have no idea this was the case unless you read about the historical context. The title of the piece is simply “The Children of Nathan Starr,” and says nothing about the death of Edward. It does not mention Edward at all. At most, as the Met catalogue entry suggests, there is a certain “heavenly light” that shines down—but on all the figures in the scenes, and they all are looking out onto a beautiful scene of a town on a river.

So, the context makes it sad, but the figures in the scene don’t know about any of that. They just exist in the happy moment. It is the sense of timeless play and childlike wonder that the artist immortalizes, not the loss itself.

I also wondered at the mention of Nathan Starr in the title, and yet the portrait does not show Nathan. It’s almost as if he is meant to be the observer of the scene, looking at his happy family, existing forever in a place without death. It’s very difficult to make a memorial portrait uplifting, especially when the deceased is a child, but Andrews seems to achieve it in many ways.

Let’s move forward in time a little bit to the early twentieth century. Sometimes, paintings of kids capture a more meditative way of being. One of my favorite Diego Rivera pieces is Blue Boy with the Banana, completed in 1931:

There is so much one could say about the historical context and the place of the work within Rivera’s oeuvre, which others have done much more eloquently than I could. Here, I want to focus on the boy himself. Slightly rumpled and holding a snack, Rivera’s blue boy seems like maybe he’s come in from playing outside. With the title being what it is, I wonder if this is a response to Thomas Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy, which depicts a young aristocrat. In contrast, this blue boy here is wearing simple clothes and sits on a simple chair, and yet something about his demeanor has an undeniable stateliness.

The Norton Simon catalogue entry notes the figure’s slightly distorted features, but what I find myself focusing on is the directness of his gaze somewhere off the canvas. In contrast to so many other scenes of children, this blue boy with the banana is sitting quite still.

This is intriguing; in ancient thought, the child was characterized as being always in a state of motion, and the child’s fast-moving body and mind were theorized as being too chaotic, too preoccupied with movement, to do things such as use reason and logic. But the little boy here sits like a king or a philosopher, peeling the banana with a small, methodical motion. There is an intensity to the portrait that also seems perfectly apt for childhood’s propensity towards approaching deep ideas with youthful innocence and candor, which often yields more profound results.

Scholarship has theorized that Rivera was also thinking of the so-called “Blue Four”, a group of European painters represented by Galka Scheyer, the art dealer for whom Rivera made this piece. The Blue Four in question were European painters Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Alexej Jawlensky. If this is so, and it seems probable, then this isn’t truly a portrait of a real child, but to me the work seems to capture some essence of childhood that is very real.

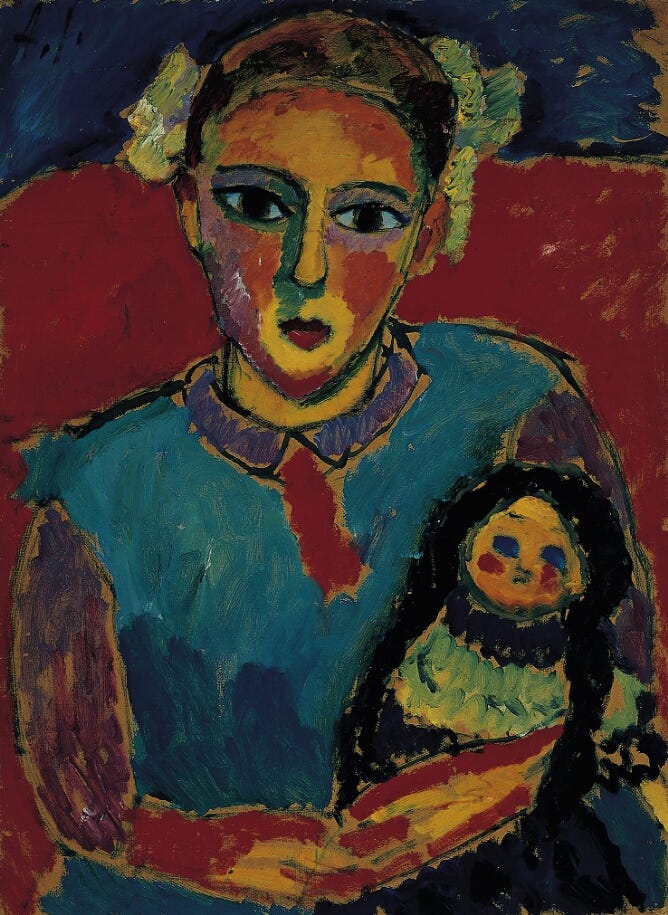

To wrap up for today, let’s look at a painting from one of the Blue Four, Alexej Jawlensky:

As it so happens, the girl pictured here is wearing a blue dress, with purple and red accents. The red of her cheeks picks up on the red cheeks of her doll, whose presence suggests that the child is in the process of playing. Like Rivera’s blue boy, this blue girl also has a certain intensity in her gaze that gives her a wisdom beyond her years. And maybe this is a unifying point across all these works: the child’s innate desire to embrace (and indeed create) play and fun speaks to a deeper wisdom that adults would do well to try and recapture.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter!

In my opinion, looking at art is one of the best ways to nurture the “inner child” (and is great for actual children too!). Indeed, just as these works depict children, whether real or idealized, they also encourage the viewer to see with the world with a child’s wholehearted sense of wonder. A good reminder.

Take care until next time.

MKA

I’ve been inspired by the number of folks I’ve come across on Substack who are embarking on self-study of art, history, culture, literature, etc. If that describes you, I have something for you! From now on, I’ll be including a few discussion questions for further reflection to help you articulate your own thoughts and interpretations. Let me know your thoughts in the comments!

QUESTIONS FOR FURTHER REFLECTION

Children are frequently associated with innocence, joy, wonder, and play, and are often juxtaposed with adults. What about more solemn portrayals of children, such as Rivera’s Blue Boy or Jawlensky’s Child with a Doll? What qualities or moods do these kinds of portrayal evoke?

Why do you think children are so often portrayed in moralizing scenes, as we saw with Mulready’s work?

Reading Art posits that our immediate reactions to art are just as valid as well-studied analyses, and here I don’t always talk much about the historical context. Still, the context of a given work can be very helpful for interpretation. Consider or do research on the historical periods of each artist featured here. How do you think the historical circumstances informs the artistic portrayal of children? Or does the context not have as much influence?