Artemis of the golden quiver: a closer look at this goddess full of contradictions

The wild goddess of the hunt, maidens, fertility, and childbirth was a force of nature in the Ancient Greek and Roman pantheons

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

I sing of Artemis of the golden quiver, she of the fearsome voice,

the reverent maiden, the huntress of deer, the one who pours out arrows,

the twin sister of Apollo of the golden sword,

who, all along the shadowy mountains and the grassy hills

delights in the hunt and draws forth her golden bow,

sending forth the grievous arrows; and they tremble, the peaks

of the tall mountains, and the wooded forest resounds

terribly with the clamor of the beasts, and both the earth and

the sea full of fishes shudder; and Artemis, having a mighty heart,

turns in all directions, slaying the race of beasts.

But once she is entirely pleased, she who watches for beasts and pours out arrows,

and is gladdened in her mind, she lets slack the well-bent bow

and goes into the great halls of her twin brother,

Phoebus Apollo, to the fertile land of Delphi,

where she directs the lovely dance of the Muses and the Graces.

There, once she’s hung up her back-stretched bow and arrows,

she leads the dance, having lovely raiment on her skin.

And they, pouring out their ambrosia-sweet voices, commemorate in song

lovely-ankled Leto, who gave birth to the children

of the immortal gods, children who are exceedingly best

in their planning and in their deeds.

Farewell, daughter of Zeus and lovely-haired Leto!

But I will commemorate you again, and another song as well.

—Homeric Hymn to Artemis (translation by MKA)

In this archaic Greek hymn from approximately the sixth or possibly seventh century BCE, the singer reveres the goddess Artemis, one of the most complex and nuanced goddesses in the Greco-Roman pantheon. Artemis—or Diana, as she was called among the Romans—was the goddess of the hunt as well as the wild in a more general sense. She was famously one of the three maiden goddesses; according to Hesiod’s cosmological poem Theogony, she specifically asked her father Zeus to be allowed to never marry, and therefore never have any children. Interestingly, she was also the goddess of fertility, which may have originated from an obscure myth in which she was born before her twin brother, Apollo (god of prophecy, healing and music), and then immediately began to help their mother deliver him.

Naturally, Artemis was especially beloved by young women and was said to be a sort of patron goddess for them from birth until the birth of their first child. She was a rare example of a female figure who existed outside of the normal societal paradigm.

In the hymn, the singer praises the goddess not only for her ability to hunt, but also to sing and dance and create beauty in the world. In today’s virtual gallery tour, we’ll explore the ritual worship of Artemis in material culture, in addition to some more modern portrayals of the goddess as well. As you’ll see, Artemis is not all fun mountain hunts and dance parties with the Muses and Graces: her ruthless side mirrors Mother Nature’s own.

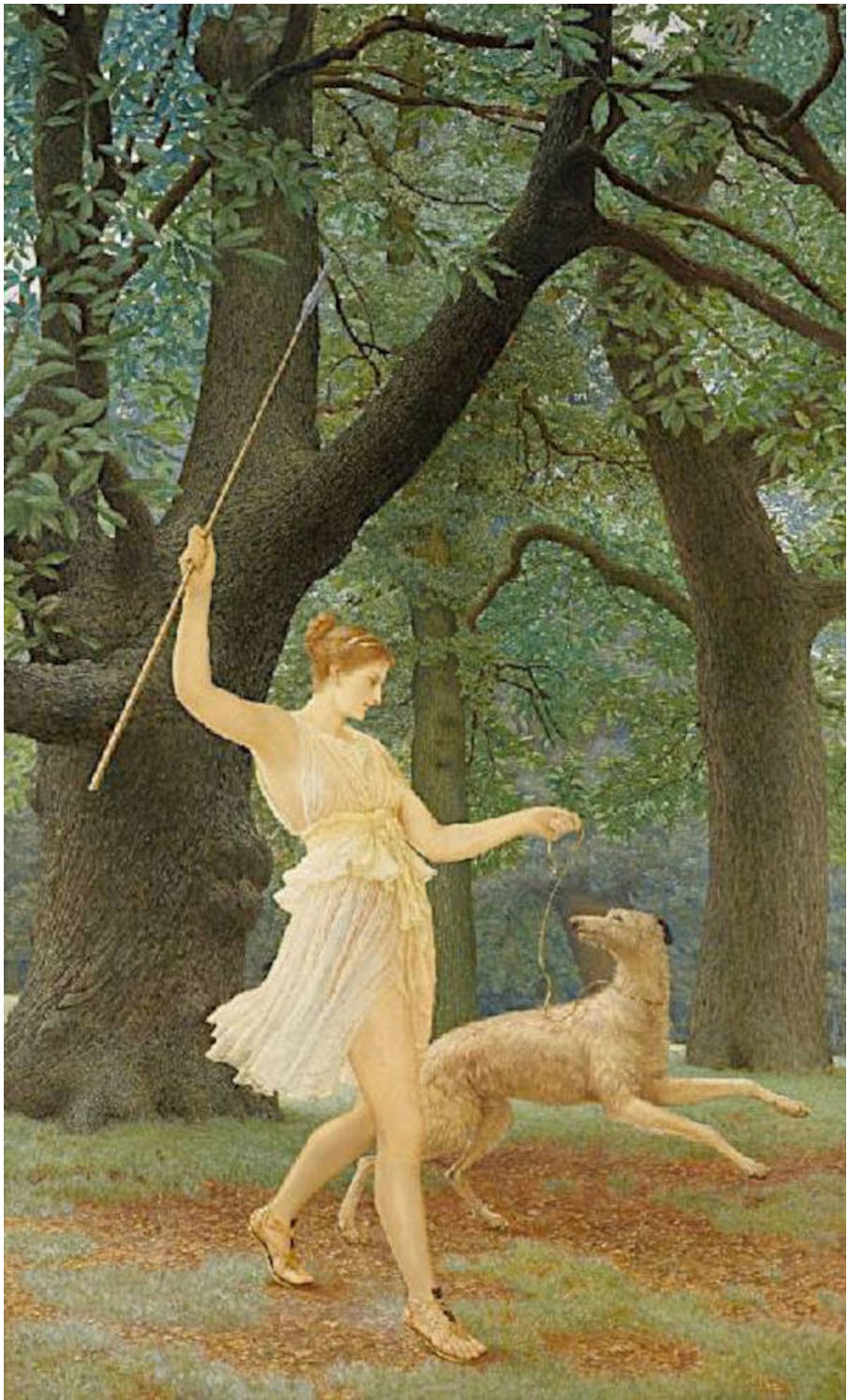

Romantic artists were especially fond of Artemis/Diana and tended to portray her in an ethereal sort of way. I particularly love this youthful and carefree portrayal of her from the late nineteenth century:

Although Artemis is holding a spear, the emphasis is much more on her relationship with her hunting dog, who plays at the end of a leash, not so much a wild beast as a cherished pet. With her soft drapery and lighthearted attitude, this Artemis seems very much like one of the young girls for whom she served as a patron and protector. Fittingly, the title of the work refers not only to her beauty, but also her chastity; the artist seems to link Artemis with purity.

The worship of Artemis was widespread throughout the ancient world and particularly thrived at Brauron (Attica, in mainland Greece) and Ephesus (in the eastern part of the Greek world). At Brauron, it was said there was a festival called the Brauronia, where there were a variety of rituals to honor the goddess. Most notably, girls would perform a ritual dance, and some accounts suggest they might have dressed up as bears or other wild animals while they were performing.

Of course, Artemis was worshipped in many other places as well, not just by girls and women, and she had her own priestesses and priests. As Roman travel author, geographer, and cultural historian Pausanias writes (8.13, translation by W. H. S. Jones):

In the territory of Orchomenus, on the left of the road from Anchisiae, there is on the slope of the mountain the sanctuary of Artemis Hymnia. The Mantineans, too, share it . . . a priestess also and a priest. It is the custom for these to live their whole lives in purity, not only sexual but in all respects, and they neither wash nor spend their lives as do ordinary people, nor do they enter the home of a private man. I know that the “entertainers” of the Ephesian Artemis live in a similar fashion, but for a year only, the Ephesians calling them Essenes. They also hold an annual festival in honor of Artemis Hymnia.

The former city of Orchomenus was on the peak of a mountain, and there still remain ruins of a market-place and of walls. The modern, inhabited city lies under the circuit of the old wall. Worth seeing here is a spring, from which they draw water, and there are sanctuaries of Poseidon and of Aphrodite, the images being of stone. Near the city is a wooden image of Artemis. It is set in a large cedar tree, and after the tree they call the goddess the Lady of the Cedar.

Just as Artemis herself was a maiden goddess, so too are her priests and priestesses expected to live “pure” lives, going above and beyond just being celibate. This was fairly common for religious officials in antiquity, just as it’s not unheard of in modern religions.

As the passage shows us, the unique geography of a place had some influence on how a deity was worshipped. In this instance, Artemis was given a cult name “Lady of the Cedar,” a nod to Orchomenus’ cedar trees and the site of her cult statue, which would have been seen as a proxy for the goddess herself.

Turning to the eastern Greek world, you might recall from last week’s newsletter on bees that we actually saw an image of Artemis from her large and famous temple at Ephesus:

Here’s a photograph of a similar statue that was at the Vatican, also of Diana/Artemis:

Images like these emphasize Artemis’ connection with animals and the natural world. From bees to griffins, her garment makes her one with the beasts she both loves and loves to hunt.

It’s a bit unclear what the blobs on the bodice of the dress are, but some scholars think they might be bulls’ testicles, a symbol of fertility (they could also be eggs, according to others, another sign of fertility).

Indeed, in the Roman world Artemis was often worshipped alongside other nature/agriculture/fertility gods, as we see on the side of this altar to the goddess:

This smaller altar was dedicated by one Aurelius Thimoteus; as you can see, worship of Artemis was not limited to women. Also portrayed alongside Artemis (or Diana, more rightly for the Romans) is a woman making a sacrifice to the native Italian god Priapus, a rather scary agriculture and fertility deity who was known for his large phallus and a penchant for threatening trespassers onto his land with sexual violence (I know, I know, the Romans were extremely weird, repressed, and overall problematic, but stay with me).

It was not uncommon in the ancient world for Greek deities to be combined in a way with indigenous counterparts. Oftentimes, worshippers would smash their names together and call it a day. For example, the Romans were known to worship Hermanubis, a god who was a combo of—you guessed it—Hermes and Anubis, combining the Greek messenger god with a god from Egypt.

Same went for Artemis, more or less, in different parts of the world. Here’s a statue of Artemis Bendis, a combo goddess of Artemis and also Bendis, a native deity of Thrace (modern day Bulgaria):

Here, she wears a Phrygian-style cap and a long sleeved tunic, garments that are identifiable with the styles of the eastern Mediterranean world.

Altogether, Artemis had what probably numbered millions of worshippers, and people really seemed to feel a personal connection with her. In the material record, there are some one hundred thousand of these little votive statues of her:

This one is much older than the altar (7th century BCE vs. 3rd century CE), but there are many examples from a range of time periods.

So far, we’ve seen Artemis as a benevolent goddess of nature and fertility. But she had a darker side as well; like all the Greek gods, she could be petty, jealous, and vengeful, and she certainly did not waste any time in punishing mortals who offended her. Nineteenth century painters were especially taken with this contrast between Artemis the beautiful and pure maiden and Artemis the vengeful god.

As one myth goes, Queen Niobe was a woman with a large number of children, and this was what she was most proud of in her life. One day, Niobe became so arrogant that she dared to boast that she was better than Artemis who, being a virgin goddess, obviously didn’t have any children.

Well, that went over about as well as you would expect. Immediately, Artemis came down from Olympus with her equally angry brother Apollo, and they both shot all of Niobe’s children dead with their arrows. According to the Roman poet Ovid (Metamorphoses 6.146-203), Niobe was so sad that she turned into a statue, which can be seen weeping even to this day.

In another legend, Artemis was once bathing in a forest pond with her attendants when the very unlucky mortal prince Actaeon came along and either accidentally or on purpose—depends on the version—saw her in the nude.

At once, Artemis splashed some water on him, turning him into a deer. Then she turned his own hunting dogs on him, and he was killed in a gruesome hunt.

But Artemis had a great capacity for love towards humans as well. In Euripides’ tragedy Hippolytus, the playwright tells the tragic story of Hippolytus, who was a young and handsome hunter. He was great friends with Artemis, and she was said even to love him. Now, inspired by Artemis’ celibacy, Hippolytus declared that he too would be a virgin forever, which was even more subversive for a man than it was for a woman. Offended by this declaration, the love and sex goddess Aphrodite brought about his doom.

But at the end of the tragedy, which is very poignant, Artemis comes down to mourn for poor dead Hippolytus, killed in a chariot accident by Aphrodites’ machinations and tragic human failings.

Artemis declares that she cannot truly grieve for Hippolytus, for immortals want nothing to do with mortal death. All the same, she says, she loved Hippolytus as much as she was able, a bittersweet summation of the close yet utterly distant relationships between humans and gods.

Similarly, Artemis was said to have become taken with the human prince Endymion. Unwilling to offer him marriage, yet undeniably attached to him, Artemis put him into an eternal state of sleep so that she could visit him every single night. I find these two myths some of the most compelling and ambiguous stories about Artemis and the immortal experience. How deep can a god’s love run for a human? How close can they become? These were questions that keenly interested the Greeks, and ones with no easy answers. Ultimately, Artemis represents a life outside the mainstream and the freedom to be wild and untamed—whether for good or ill depends on the goddess’ mood, much like Nature herself.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter!

Artemis is one of my favorite Greek goddesses. We barely scratched the surface when it comes to portrayals of her! She’s definitely one of the most nuanced deities.

Happy Earth Day this week!

Take care until next time.

MKA

QUESTIONS FOR FURTHER REFLECTION

Why do you think Artemis, goddess of the hunt and the wild, was said to be the twin of Apollo, god of healing and prophecy? How do these two gods’ roles complement each other? How do they not?

The gods are defined by their inability to die or be touched by death. What does Artemis’ response to human aging and death say about the ideal god/human relationship?

Why do you think that girls/first time mothers had a patron goddess, but there’s no true counterpart for boys?

In the Homeric Hymn to Artemis, Artemis is described as being a companion of the Muses and Graces. How does she fit in with these other deities?