Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

The week between Christmas and New Year’s is always a quiet time for me, especially since I’ve always worked in higher education and adjacent roles with organizations that do a holiday closure for the week. I’m taking this time to jot down some goals for 2025 and reflect on the progress I’ve made in the past year. My dissertation has seen a lot of progress this year! Now that I have the complete draft, the last few months of my PhD will be editing and refining.

For this sleepy, liminal week, I thought a good virtual gallery tour topic would be allegory—let’s embrace the energy of this week and think about all things symbolic, subjective, and even downright obscure. Allegories often appear in literature, such as the philosopher Plato’s famous “Allegory of the Cave,” in which he uses a fable of some people chained up in a cave and only able to view the world via shadows on the cave wall. Plato used this story as a means of explaining the often-flawed way in which we perceive reality. But allegory is just as expressive in art: it adds another layer of nuance to the piece, and it is generally up to the spectator to decide what exactly that nuance involves.

As you can probably tell if you’re a regular reader, I’ve been very into Northern Renaissance paintings as a nice little balance to all the work I’ve done on philosophy in Ancient Rome for my dissertation. Dutch painters loved to use symbolism and allegory in their works to convey a greater depth of meaning. We’ll look at some examples from this art historical period and others as well.

Pictura: An Allegory of Painting

Oftentimes the allegorical nature of a painting will be in the objects around the main subject. For example, clocks often represent the passage of time, while skulls might represent death (two common examples from painters like Hans Holbein and others of this time period). In these cases, the artist usually won’t overtly point to the allegorical nature of the work by making these features too prominent or by giving it an obvious title.

But sometimes they will! See, for instance, Frans van Mieris the Elder’s Pictura: An Allegory of Painting:

There’s two layers of allusion here. On one level, Painting (Latin Pictura, cf. English “picture”) is personified as a human woman. I’m struck by the way in which the artist has not chosen to make Pictura into a generically beautiful “idealized” woman, but instead has given her relatable features, such as some frizz around her hairline and even the hint of a double chin. Maybe this makes Painting more relatable, or maybe it hints at the fact that the skill and task of painting is hard work and takes a lifetime to master—if indeed mastery is ever fully possible. It also might suggest that the painter’s presence is essentially an invisible one; it is the results produced that get the accolades and are seen as aesthetically pleasing.

On another level, the objects in her hands also possess allegorical meaning. The paintbrush and palette are fairly obvious. The mask on the heavy gold chain around her neck signifies, perhaps, that painting can create illusions. I think it can also mean that the painter in question can assume a range of different identities or personalities as expressed in the art that is created. There’s also possibly a nod to ancient theater masks, indicating that the act of painting and the painting that results are both forms of performance, sparking the imagination in new ways for every new spectator. I wonder about the chain: is the painter constrained in some ways? By convention? By his patrons’ expectations? By the unshakable desire to create that drives every artist?

I love how Pictura’s arm mirrors the posture of the classical Greek-looking figurine in her arms. There’s a sense of concealing and revealing in both figures, which is another task of the painter. The statuette is unpainted, perhaps awaiting Pictura’s touch. All ancient statues would have been brightly painted; the cool white exterior we associate with classical sculpture is an illusion made by the passage of time. So perhaps here Pictura is going to render a sculpture in all its classical glory, adding color to the colorless. Another possibility is that she’ll use the figure as a model, to bring the subject to life in another medium.

Another allegory of painting!

I came across another scene of the personified form of Painting, this one in the collection of the Smith College Museum of Art. It’s very interesting to compare:

This piece is oil on glass, probably dating to around 1800 and produced in China, although the artist is unknown. It is interesting that the caption reads PAINTING in English, so I’m assuming this was made specifically for a Western audience.

Anyway, here we see the much more typical idealized feminine form in the figure of Painting, and when we view this work in conversation with the last we really see how striking Mieris’ decision was to un-idealize Pictura.

In this case, the artist has chosen to focus on the sensuality of painting, surrounding her with little cupids and portraying her seminude, like a Greek statue of Aphrodite. Painting is an expression of love in many ways, for art, for the subject, for the cultivation of creativity. It also creates beauty—which, to return to Plato again, can be a conduit for understanding of greater truths (for further details, see Plato’s Symposium). I’m sure the medium (oil on glass) impacts this, but I love how Painting herself seems half-come to life, like the subject on her canvas. For the most part, she seems to be in faded colors, almost greyscale, but the luster of her blue garment deepens in color as the eye moves down her body.

The challenges of human life

In other cases, it’s not exactly a personification that constitutes the allegory. Instead, something that seems obvious is actually an allegory for a different or alternative meaning. Next, since we’ve considered the sculptural nature of personified Painting, let’s look at some actual sculpture.

This is Rodin’s The Thinker, originally part of the monumental sculpture The Gates of Hell, which portrays a scene from Dante’s Inferno:

We’ve all fallen prey to overthinking at one time or another, so maybe that’s what Rodin was getting at with the inclusion of a “thinker” in the “Gates of Hell.” Originally, this piece was called The Poet, representing Dante as someone who was tormented in his soul but also liberated by the act of literary creation. The way this piece reflects the meditative state of contemplation and simultaneously the torture of being too trapped in one’s thoughts is so compelling.

Jumping back a few centuries again, I want to spend some more time on the ways in which artists use allegory to illustrate the possible pitfalls of humanity. Hieronymus Bosch absolutely loves to explore the darker side of humanity, as he does here in his Allegory of Intemperance, originally paired with another work, The Ship of Fools, that together symbolized the sin of Gluttony:

To be honest, there’s not a ton of nuance to the allegory here, or at least it seems fairly literal to me. There’s a scene of some people engaged in a sort of horrific gluttonous dinner party, emphasizing their intemperance. The dark colors and indistinctness of the scene—it kind of reminds me of T. S. Eliot’s infamous wasteland, for some reason—further underscores how far these souls of fallen. Of course, this is a moral allegory too, not just for literal over-partying but for the other intemperances or excesses of life. How much this was actually a problem is debatable; people have been complaining about the excesses of their time period since antiquity and probably even before that too. But still, Bosch’s work captures the moralizing tone that seems to characterize this period in history.

People went wild for this sort of thing in Bosch’s day. I wonder if they found some sort of perverse delight or even Schadenfreude in spectating the fallen states of others, or if it was kind of like an anti-mood board of what not to do in life.

This piece was part of a triptych that probably originally included the whole gang of Deadly Sins, as well as this charming work, Death and the Miser:

This one is especially creepy. The abandoned armor in the foreground maybe signifies the collapse of the strength or courage or will to do better in life—hopefully the spectator will be inspired to have more resilience in the face of vice and sin. Way at the top, you’ll notice a little stained glass window of Jesus on the Cross, complete with a beam of sun faintly shining down and failing to reach the Miser, foreshadowing of what’s probably to come for him after his eventual demise (almost certainly not Heaven). An angel tries to get the Miser to look up at Jesus and find salvation, but he’s enthralled by the demon beside him, trying to tempt him with one last bag of gold. The Death-Skeleton coming in the door is aiming a javelin right at his heart, and things aren’t looking too good for our Miser.

To look at an allegory of Greed in another, more subtle way, let’s turn our attention next to this famous painting depicting the mythological scene of Danaë, a Greek heroine:

As the story goes, Danaë’s father, King Acrisius, was very opposed to her getting married. The reason for this was that the king had heard a prophecy that he would never have a son, only a daughter, and this daughter would have a son—who would grow up to kill Acrisius. As a result, Acrisius came up with the brilliant plan to lock his daughter in a tower so that nobody could get to her. Fortunately—or unfortunately, depending on how you look at it—the god Zeus fell in love with Danaë. The myth gets a little vague here. It says he “came to her in a shower of gold,” and after that she conceived her son, the hero Perseus. Don’t think too much about how that happened.

Again, unclear on what exactly constitutes a “shower of gold.” But I love how Orazio Gentileschi visualizes it for us as a little shower of gold coins. Danaë (and the little Cupid to signify what’ll happen next) just look excited to get some unexpected money. Unless they realize this is Zeus? We just don’t know. But what I can say is that some scholars have posited that Gentileschi had two meanings in mind: one is the mythological story, and the other is an allegory about greed and/or morality in a broader sense.

The Unknowability of Allegory

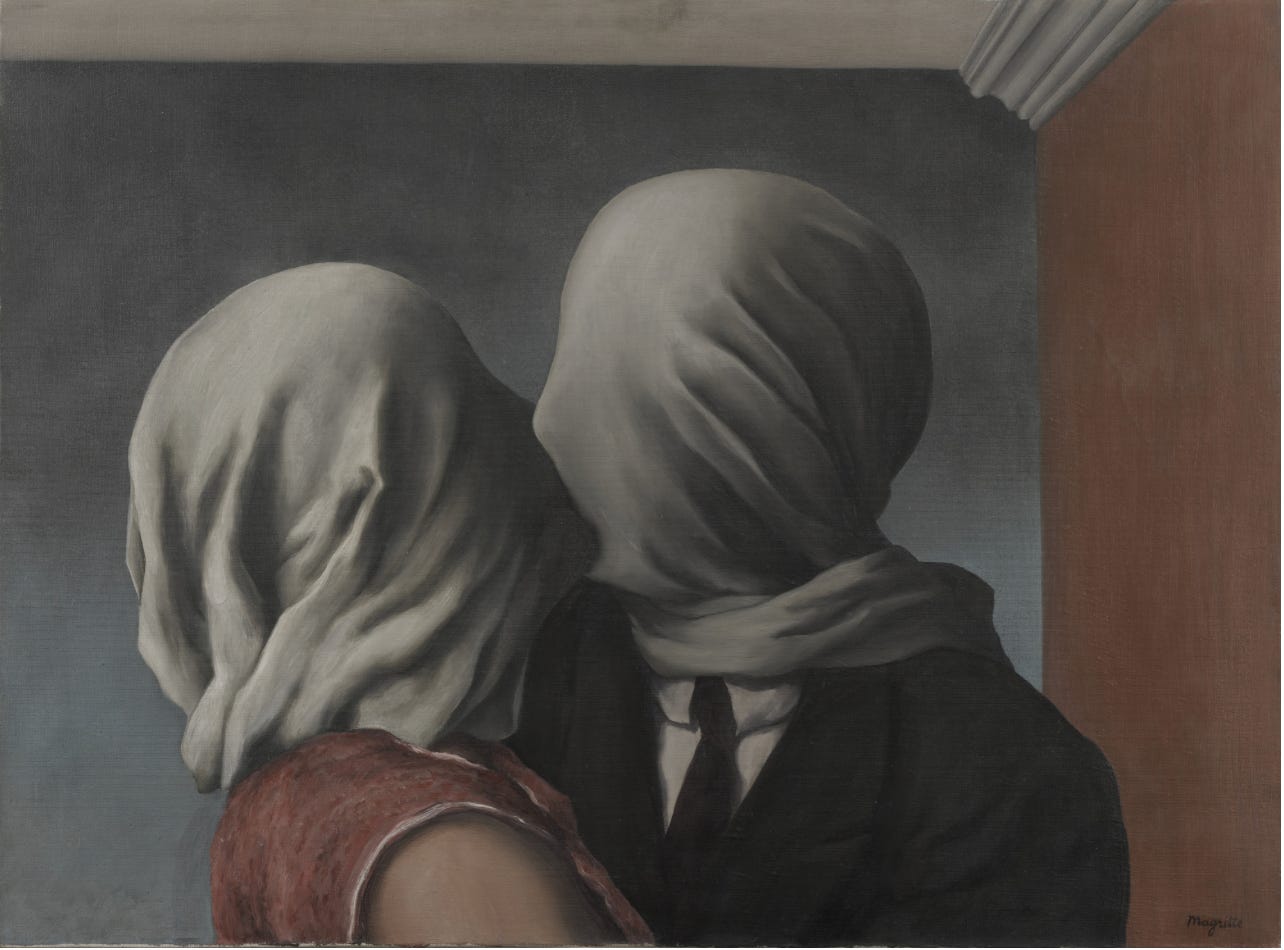

To end today’s virtual tour, I want to look at something much more recent than any of our other works of focus and turn to twentieth century surrealism with Magritte’s The Lovers:

In the scene, a couple kisses, but their faces are obscured and separated by veils or sheets of cloth. While many have rushed to unpack the symbolism and assign some kind of meaning to the image, the artist himself argued for its unknowability (see the catalogue entry by MoMA);

They evoke mystery and, indeed, when one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself this simple question, ‘What does it mean?’ It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing either, it is unknowable.

This is one of the general ideas behind surrealism and its close cousin absurdism: there really is no heightened meaning. But I would argue with Magritte (if only I could) that unknowability is not the same as meaninglessness. We may be like Plato’s cave-people, only grasping the shadows of reality, but our capacity to conjecture can still get us closer. But for now perhaps we can rest our case with Magritte and simply say that The Lovers is in essence an allegory of unknowability, whatever that might signify in the end.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter!

I hope you enjoyed this deeper dive into various portrayals of allegorical elements in painting and sculpture. Happy New Year! Take care until next time.

MKA