Bones

Happy Halloween week! This week, we're looking at skeletons in art and their cultural and even philosophical significance.

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

Autumn is my favorite season, and I always especially look forward to Halloween. I usually don’t have any particular plans or do anything to specifically mark the day, but it’s a fun soft launch of the holiday season.

The Romans were also here for ~spooky season~. They didn’t exactly celebrate Halloween, but they were very devoted to showing reverence for their ancestors (one traditional aspect of Halloween) and in October they had a festival to honor them, which they called Feralia. In Latin, the word feralia can refer to funeral rites. According to some sources, contact with the Celts led to the incorporation of some elements of the Gaelic festival Samhain, which celebrated the (hopefully successful) culmination of the harvest season and the approach of winter.

But the Romans’ fascination with death was not limited to October. There are a number of artifacts from the Roman period that feature skeletons in their design, often accompanied by inscriptions that say something to the effect of “you’d better live it up while you can before you die.” This statement might seem glib and cliché, but it had more significant cultural and even philosophical meaning to the Romans.

Memento mori

In Rome, triumphant generals and emperors were said to have had someone, probably a slave, whisper in their ear the words remember you will die or remember you are only human, a ritual that suggests, again, the importance of remembering that all of life’s successes and riches will eventually become meaningless at the time of death.

Unsurprisingly, philosophical schools were interested in the question of death. The Epicureans were perhaps the most notable in this regard in that they did not believe in any kind of afterlife. They did believe in a soul, but its atoms would break apart upon the death of the body and eventually be recycled into other matter. Therefore, it was especially important in Epicurean ideology to cultivate a pleasant life while it was possible to do so.

Epicureanism enjoyed a certain popularity among the general public, and we sometimes see these kinds of Epicurean ideas reflected in material culture in a bit of an exaggerated manner. This is what I call “pop culture philosophy” in Rome. People were drawn to the ideas of philosophy—especially Epicureanism, since you were allowed to have fun and weren’t obligated to give up your material possessions or anything too grim like that. Even if Epicureanism decidedly did not extend to hedonism, people just made the ideas their own. Apparently, they enjoyed what scholar Pamela Gordon memorably calls “Epicurean kitsch.” Skeleton kitsch in general abounded in antiquity, and, as we will see, more recent artists couldn’t help but be fascinated by skeletons as well.

One such example is a famous pair of silver cups found in Boscoreale (one of the two shown below, front and back):

In the scene engraved onto the cups, we see a group of skeleton partygoers eating, drinking, dancing, and playing music. A garland hangs above their heads, and the scene would be very charming indeed were it not for the fact that the partygoers were clearly dead. More fascinating yet is the fact that the artist inscribed each skeleton with the name of a famous philosopher, including Epicurus, Zeno, and several others.

It’s difficult to articulate the significance of a bunch of dead philosophers having (Epicurean) fun at a banquet. Maybe the idea is that they, or their ideas, enjoy a kind of wretched immortality that is ultimately meaningless in the face of death. Or perhaps it reflects the ideal nature of a philosophical person: carefree despite the fact that death comes for all. I also find this piece somewhat humorous, like a spoof on the fairly common literary trope of “philosophers at a dinner party,” such as Plato’s Symposium, where philosophers gather to think the big thoughts and answer the big questions—ones that generally concern the living, such as the nature of afterlife, the purpose of the mortal experience, the nature of happiness, and so on. But, as the cup suggests, once we are dead, these kinds of mortal concerns fall away. Yet simple enjoyment remains.

Skeletons are everywhere in Roman art. If you owned a villa, you might even want a giant skeleton floor mosaic, just to keep you humble:

The word written across the mosaic reads EUPHROSUNOS (ΕΥΦΡΟΣΥΝΟΣ), which means “cheerful” or “merry.” Achieving this emotional state would be a key goal of Epicureanism, with its emphasis on pleasure. Being a singular adjective in the nominative grammatical case (which signifies the subject of a sentence/phrase), it seems that the word is describing the skeleton himself, who reclines back on one elbow as though he’s sitting on a couch at a dinner party, and he holds a drinking cup in his hand. Death hasn’t gotten in the way of his merrymaking, and we shouldn’t let death’s eventuality deter us either—in fact, it should be an incentive for having fun. I’m not entirely sure what the crescent is at the top of the mosaic, but to me it looks sort of like the moon, and a nighttime motif would be appropriate here, I think. This particular example is most likely from the 3rd century CE (aka the 200s), so it’s about 200 years older than the silver cups from Boscoreale. In other words, skeleton art continued to be popular over a number of years and spanning eras of Roman history.

Works like these also seem to show a sort of irony or humor about them, which is also appealing. If you didn’t want a huge mosaic, but still wanted a nice little memento mori reminder to keep you from getting above yourself, you could also have a tiny skeleton figurine:

This particular skeleton is less than three inches tall; it might have been a bit longer if its legs weren’t mostly missing. What would someone have done with such a thing? Display it in their house? Carry it around with them? Who knows! Maybe it was the ancient equivalent of a Halloween decoration, or a child’s toy, or a gag gift. The possibilities are really endless. This example is bronze, but there are numerous other examples from antiquity, some even cast in silver. Maybe they were like those giant skeletons you can get at Costco, but in miniature form. Maybe everyone had one! I’m not sure, but I think they’re hilarious. For some reason, the skeleton has absolutely giant teeth and a wide smile. He reminds me of that emoji with the bared teeth. It look like the limbs are joined with pins, so you would even be able to make the skeleton move (or dance) if you wanted to. When I look at the skeleton, I don’t really think about the metaphysical nature of death and its ultimate meaning (or lack thereof); I just want to laugh. Maybe that’s the point.

Skeletons and the promise of death…or life?

Later eras were also fascinated by skeletons and bones. Northern Renaissance artist Hans Holbein the Younger frequently incorporates reminders of death and the passage of time in his works, but one of the most striking examples is his painting The Ambassadors, which portrays Jean de Dinteville (left), on a diplomatic trip from France to England to meet with Georges de Selve (right), the Bishop of Lavaur, also an ambassador to England:

The iconography is influenced by current events: because Henry VIII had refused to properly get his marriage annulled before remarrying, there was now a break from Catholic practices, paving the way for the rise of Protestantism. As with many Northern Renaissance painters, Holbein loved symbolism, which is perhaps not so subtle here. For example, the lute has broken strings, and the book on the lower shelf is a mathematics text open to a page on—you guessed it—division. There seem to be two globes portrayed. One of them, the lower one, is on its side, and the upper one is right side up, but its gold case looks almost like a cage. The world at large does not promise freedom and opportunity, but is somehow stuck in a holding pattern until the dust settles. Religious strife and the uncertainty around this tension permeates the portrait.

But for a viewer who doesn’t know the historical context, the work’s symbolism might resonate differently. I think the eye naturally wants to go to the odd intrusion of a flat, disc-like object in between the two ambassadors. When we view the image from the side, we see that it is in fact a human skull, although its placement is still very surreal and it looks superimposed on top of the scene, not a natural part of it. Scholars have also theorized that a special glass was used to view the skull and make it look more three-dimensional. I would love to try this out! It puts me in mind of Getty’s 2024 PST ART theme, Art and Science Collide. If indeed it was possible to essentially use science to “complete” the artwork, then I wonder if that would add another layer of symbolism: the classic tension between science and religion, which might be further reinforced by the globes and math textbook.

In other words, death seems also to be a prominent theme, and unless you know about the historical context (or even if you do), the point of this theme is something of a question mark. Is Catholic salvation now in question because of Henry’s flouting of religious doctrine? Does it refer to Henry’s apparently bloodthirsty nature? Who knows. The opulent nature of the scene, with the rich green of the curtain and the intricate detail of the floor, plus the elegant clothing, also strikes me as significant: it reminds me of the feasting skeletons.

This time, however, the effect is a little bit different: the two men seem solemn, and not at all cheerful; their material goods don’t seem to give them any comfort. They don’t really matter, but not in the same way that the Roman skeletons’ material possessions don’t matter: when the fate of the Church is up in the air, there is little humor or hope to be found. Dinteville and Selve are somehow neither dead nor alive, but in a kind of liminal state while they wait to see how current events play out and to what extent diplomatic influence can have any impact at all.

I also thought more about the skull, which only emerges when you view from the proper angle. It’s sort of like Schroedinger’s cat: the skull both does and does not exist until the viewer decides how to orient their body to look at the painting. There’s another semi-hidden element in the work: up at the very top left, there is a partially obscured image of Jesus on the cross. Viewers can somewhat easily find a prominent reminder of death, or they can lift their gaze—literally, metaphorically—and find a reminder of resurrection and the triumph over death.

In Roman thinking, death triumphs over us. In Holbein’s estimation, we can choose differently and triumph over death. Or perhaps the Romans felt this way too, and these two eras are more aligned than first meets the eye. As the Epicureans liked to say, Death is nothing to us.

The death of a skeleton

Speaking of PST ART, I recently had the opportunity to go and see a new Getty exhibition, “Paper and Light,” which explores the following ideas:

Artists have for centuries explored the interaction of paper and light. This exhibition of drawings charts some of the innovative ways in which the two media were creatively used together. Works include the Museum’s extraordinary 12-foot-long transparency by Carmontelle—essentially an 18th-century motion picture—which will be shown lit from behind as originally intended. Drawings by more contemporary artists including Vija Celmins will join sheets by Tiepolo, Delacroix, Seurat, and Manet to portray the themes of translucency and the representation of light.

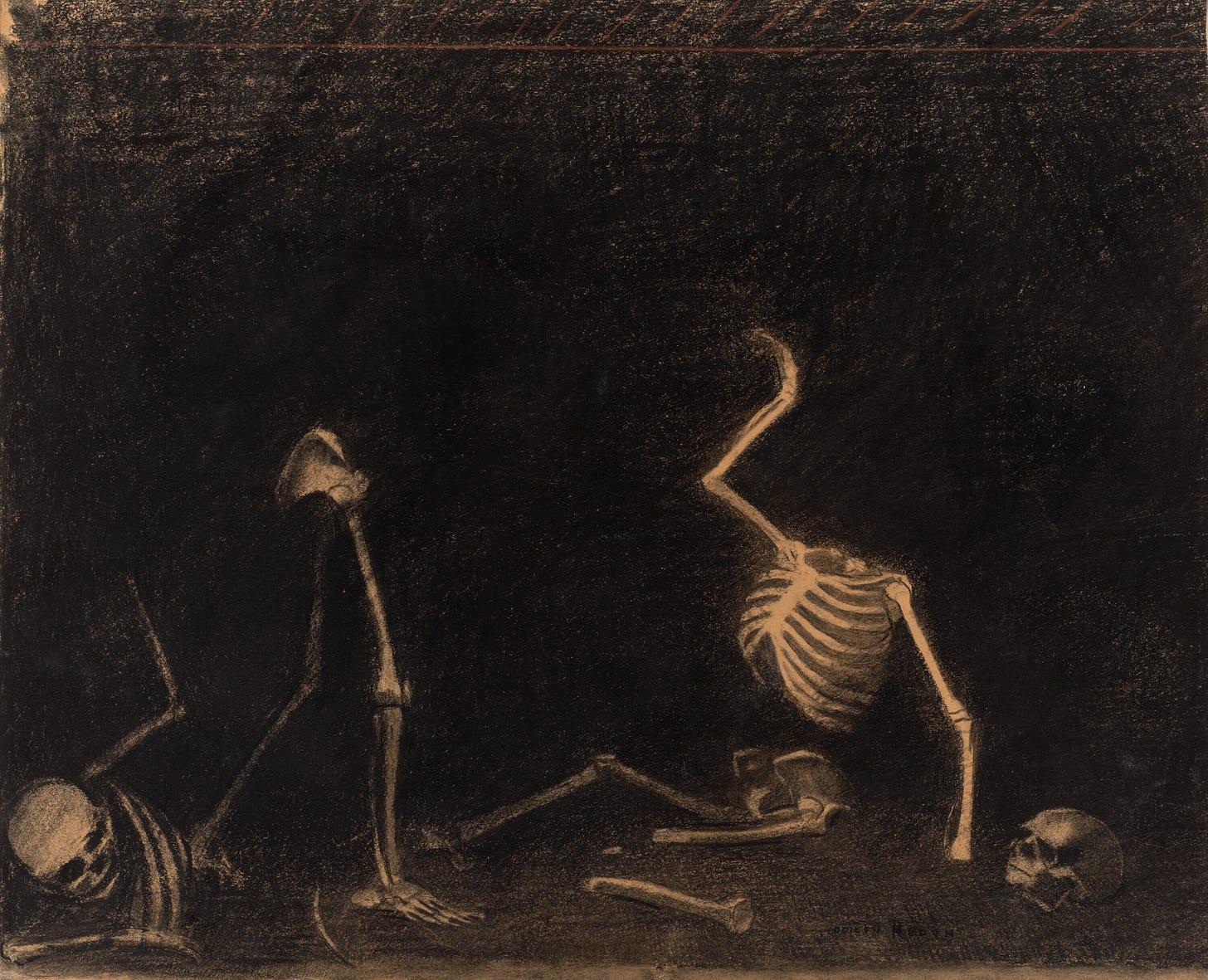

Right at the front of the exhibition was this piece, which is titled The Battle of the Bones:

Odilon Redon was a French Symbolist artist. His drawing is, superficially, much less ornate than that of, say, Holbein, but its relative simplicity belies the deeper complexities of portraying a skeleton that somehow still retains the spark of life.

The contrast of the drawing really makes the skeletons pop, and the darkness of the backdrop makes it extremely apparent that the skeletons have been broken apart by their imaginary duel—to the death? To some point beyond death? Unclear. The skeleton on the right is still raising its hand to strike at its enemy—but the point of the battle is now beyond our comprehension. Without distinguishing features or any objects around the skeletons, the very idea of fighting seems increasingly ludicrous. Still, the resilience of the skeletons and their devotion to their respective causes is perhaps admirable (or foolish).

Indeed, the image raises a complicated question: what does it really take to die? Perhaps Redon drew on metaphysical or spiritual ideas to make the point that the persistence of the soul or spirit makes death impossible. Perhaps he wanted to go for a more absurdist spin and suggest that sometimes it’s better to just give up.

Thank you for reading!

All in all, skeleton art is pretty funny, and also reveals artists’ efforts to “strip down” the nonessentials of human life and get to its core purpose and meaning. Nothing like Halloween week to spend some extra time thinking about death! Memento mori, but not too much. Best, I think, to spend our energy thinking about life.

Thank you for reading this week’s edition of Reading Art. As always, I would love to hear your thoughts. Take care until next time.

MKA