The Secrets of History

This week, we take a closer look at a first edition of Plato's works, published in the sixteenth century by the renowned Aldine Press and held in the Special Collections at UCLA's University Library.

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

One of the things I love most about being a grad student at UCLA has been the ability to do interdisciplinary work, because it’s given me a chance to expand my intellectual horizons and take on some really interesting research projects. Although I obviously enjoy working on antiquity (the Roman Empire is my Roman Empire and all that), sometimes I wish that I had specialized in early modern literature/art/culture, because it’s such a fascinating time period. So, a couple of years ago, I was excited to have the opportunity to take a class with UCLA’s visiting Speroni Professor in Italian Studies, who led a wonderful and very memorable seminar on early modern paleography, in collaboration with UCLA’s Special Collections department.

The early modern period (aka the Renaissance) was a time of discovering the joys of ancient literature. Much like in the Roman Imperial period, the aristocracy was eager to cultivate an “erudite” image and engage in intellectual pursuits. The innovation of the printing press allowed for works to be circulated more easily and quickly than before. In previous times, a scribe had to write out a text by hand in order to produce a second copy of any given work. (Yes, that meant there are a number of errors present in any given handwritten manuscript! Imagine being a monk in the Middle Ages, listening to someone at the front of a room read out a work of literature while you try to copy it down as fast as you can. Now think of how well you’d be able to do that. As one of my grad school friends puts it, we often have to rely on the hearing of a medieval monk for our version of an ancient text, lol. There are often some typos in printed editions too, of course.)

Discovering a first edition of Plato at UCLA

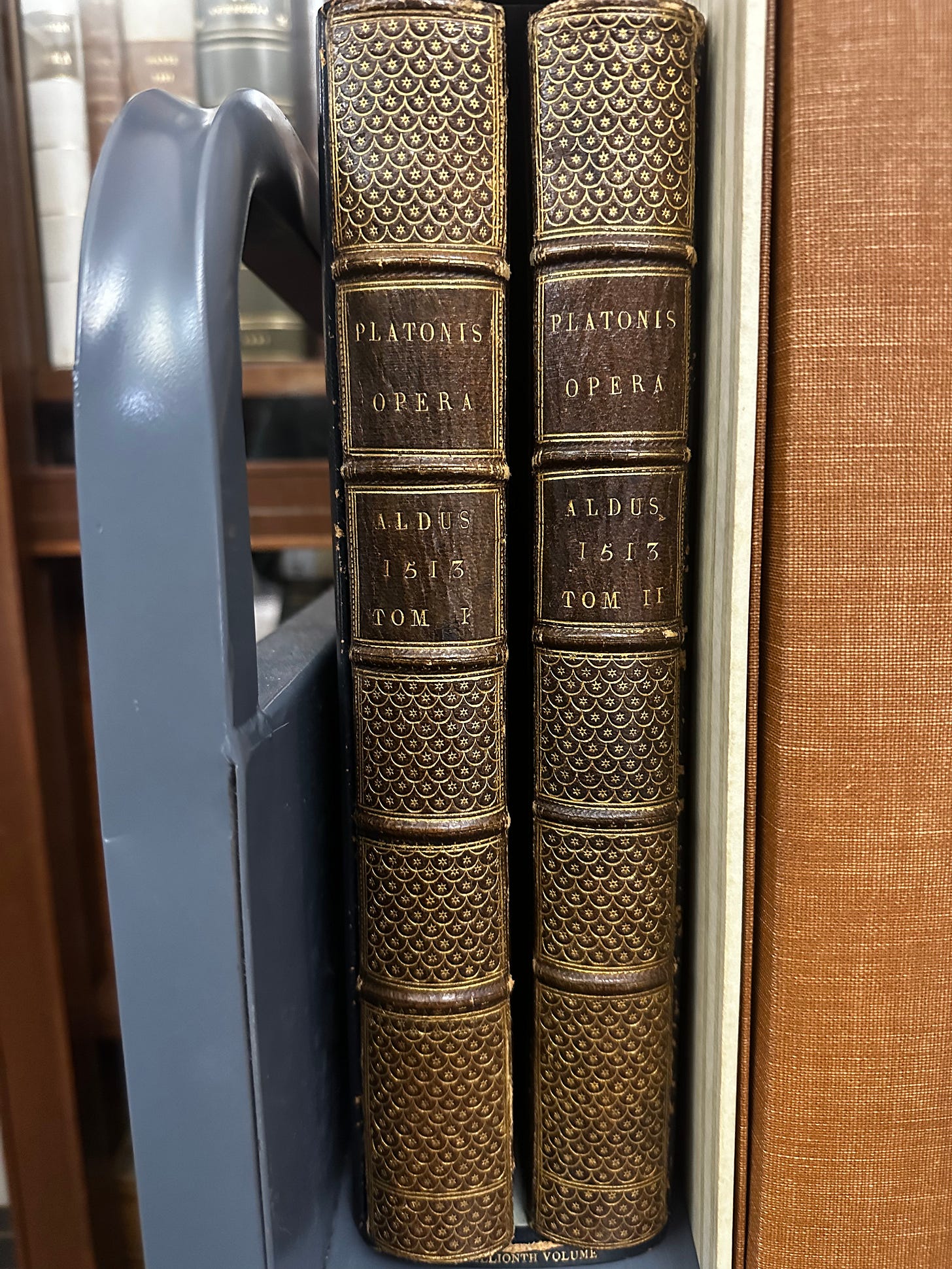

For my term paper, I decided to work on a two-volume edition of the complete works of Plato, produced by the Aldine Press in September of 1513. The Aldine Press was early modern Italy’s foremost publisher, headquartered in Venice and founded in the mid-1490s, and they were responsible for producing and then circulating a large number of ancient texts to their eager customers. The founder of the press was Aldo Manuzio, a scholar and humanist who liked to refer to himself by the Latin version of his name, Aldus Manutius.

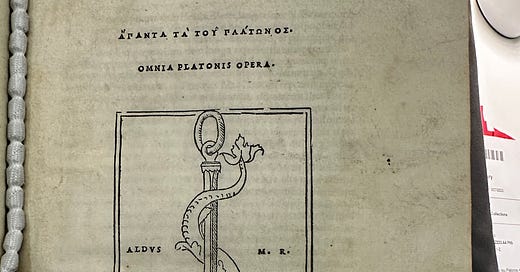

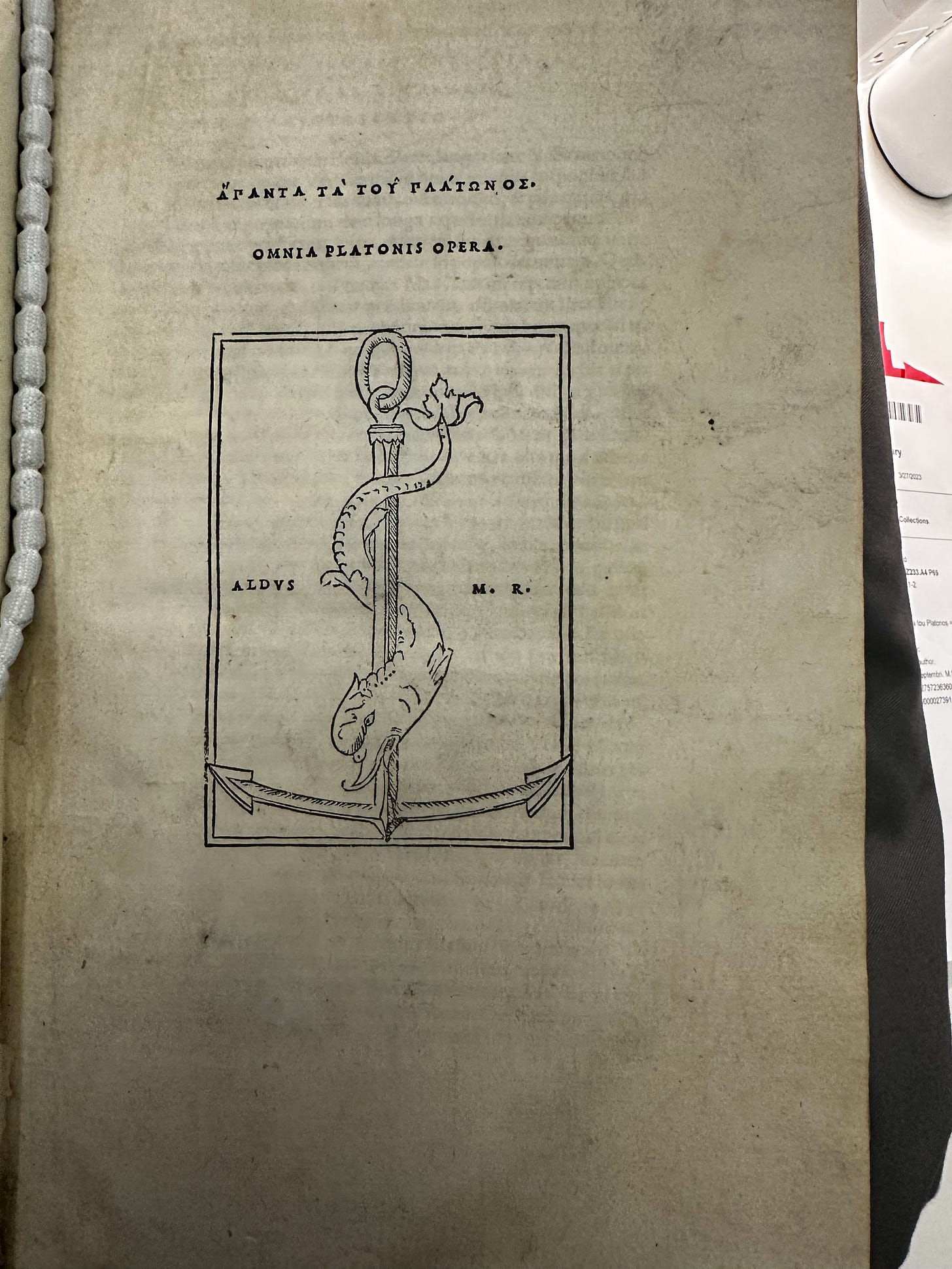

Aldine books have the distinctive imprint at the front, which has the dolphin entwined around an anchor. The Greek words above are the title, and say, when transliterated, Hapanta ta tou Platonos (All the works of Plato). Right below is the same title, this time in Latin: Omnia Platonis Opera (All the works of Plato). If Ancient Greek was a challenge for the average educated Renaissance elite, Latin would have been familiar.

The inspiration for the logo was allegedly a silver coin from the Roman Imperial period that had a similar motif on it.

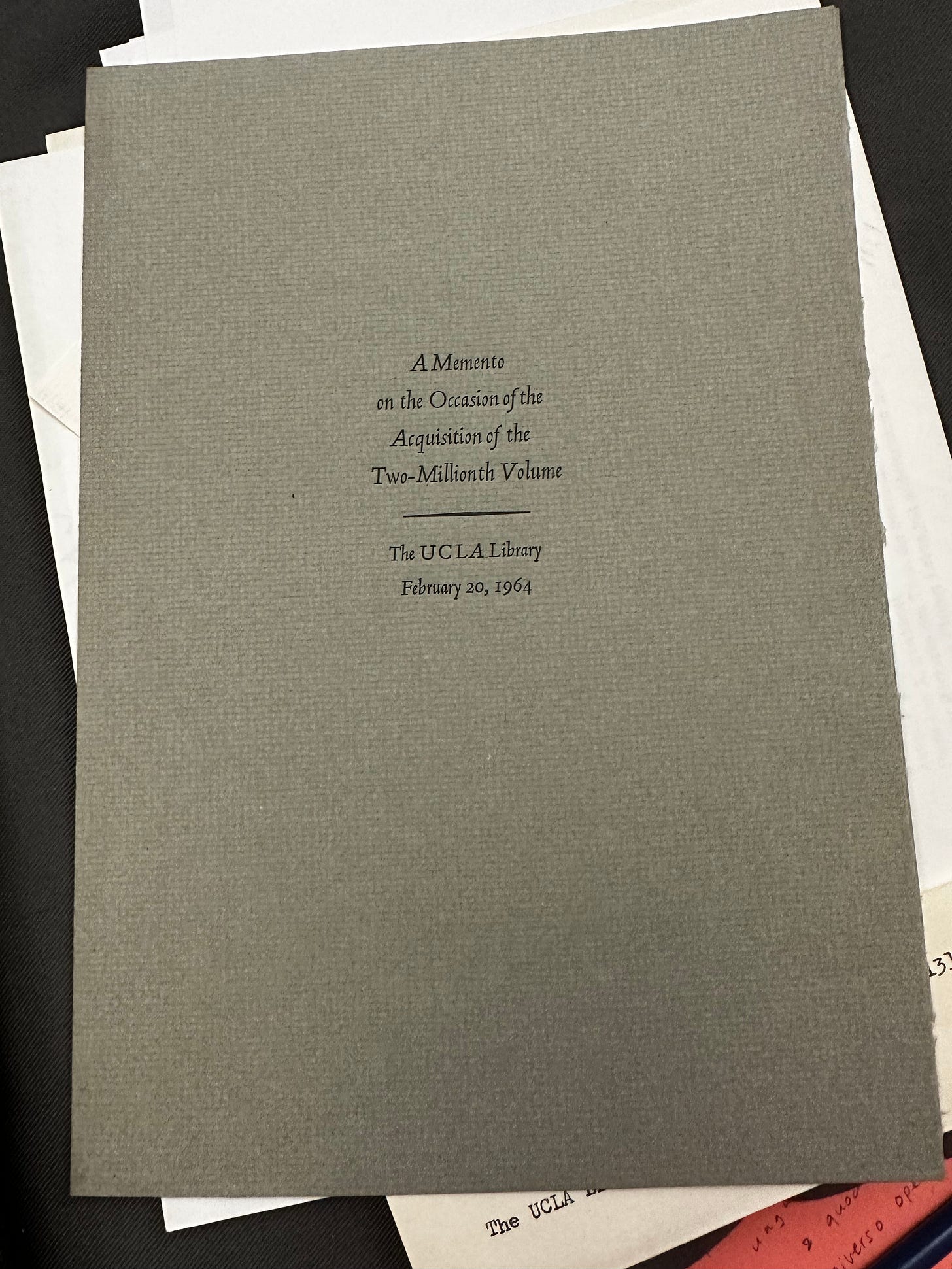

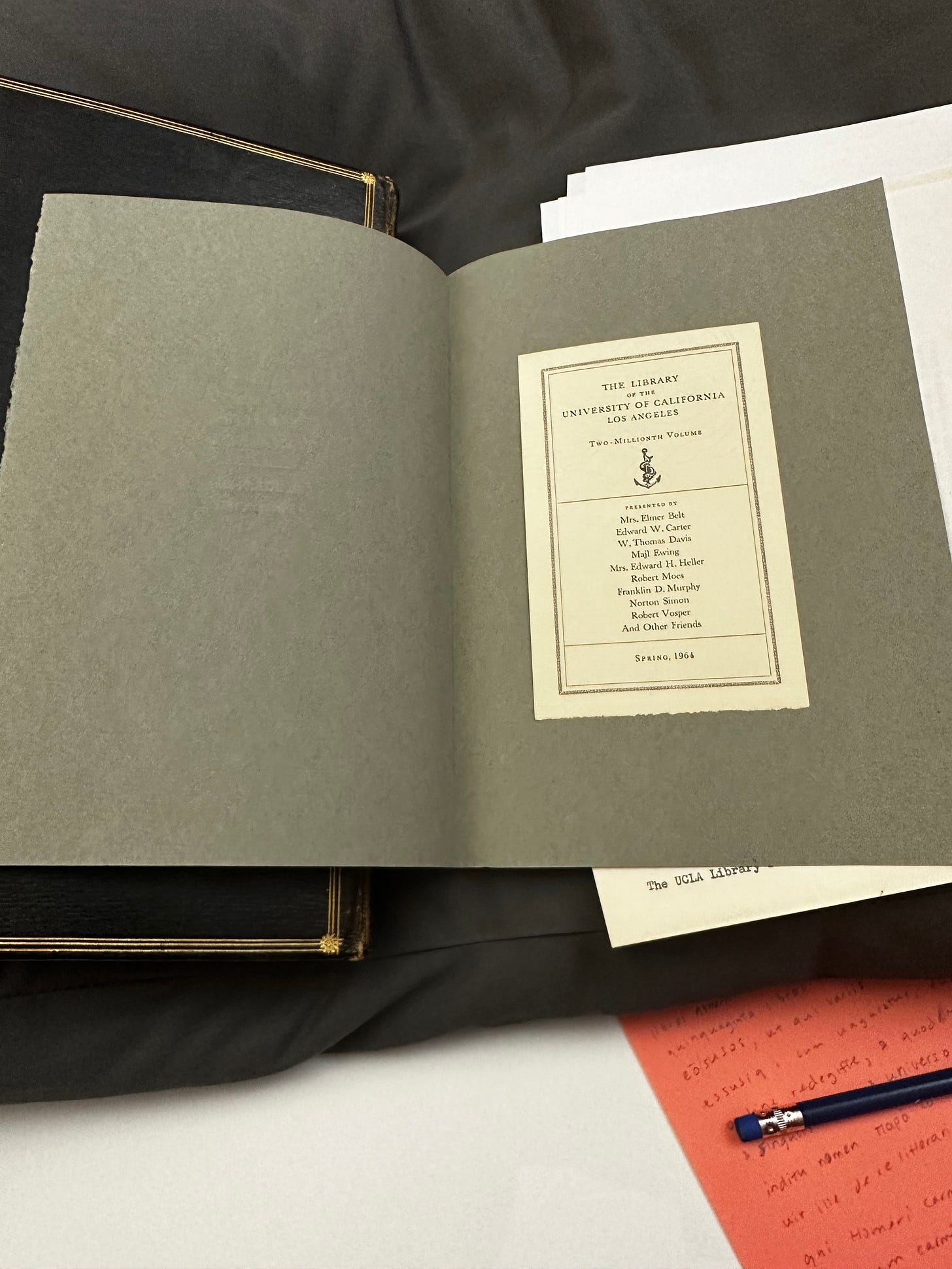

What interested me in this case was not so much the text, although I am very fond of Plato, and the Greek type (font invented by Aldus himself) is truly wondrous (just read up on the printing process in the sixteenth century). What intrigued me more was the book itself, for a number of reasons. First, when I opened up the book, I was surprised and delighted to find a little booklet proclaiming the book the library’s two-millionth acquisition, which was celebrated back in February of 1964:

The booklet reads: “A Memento on the Occasion of the Acquisition of the Two-Millionth Volume / The UCLA Library, February 20, 1964.” The inside of the booklet lists the names of those presenting the volume: “Mrs. Elmer Belt; Edward W. Carter; W. Thomas Davis; Majl Ewing; Mr. Edward H. Heller; Robert Moes; Franklin D. Murphy; Norton Simon; Robert Vosper; And Other Friends.” 1964 marks the first time in the volumes’ history that they were owned by a university and not a private individual. Franklin D. Murphy was one of UCLA’s most distinguished chancellors, and Norton Simon was a philanthropist and art collector, much of whose collection is now at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, CA.

But UCLA was not the book’s only known owner. In fact, there were three others, according to evidence left behind in the volumes themselves. Untangling their identities and possible relationships to UCLA’s Aldine Plato formed the basis of my project. I started with the bookplates at the front of the first volume:

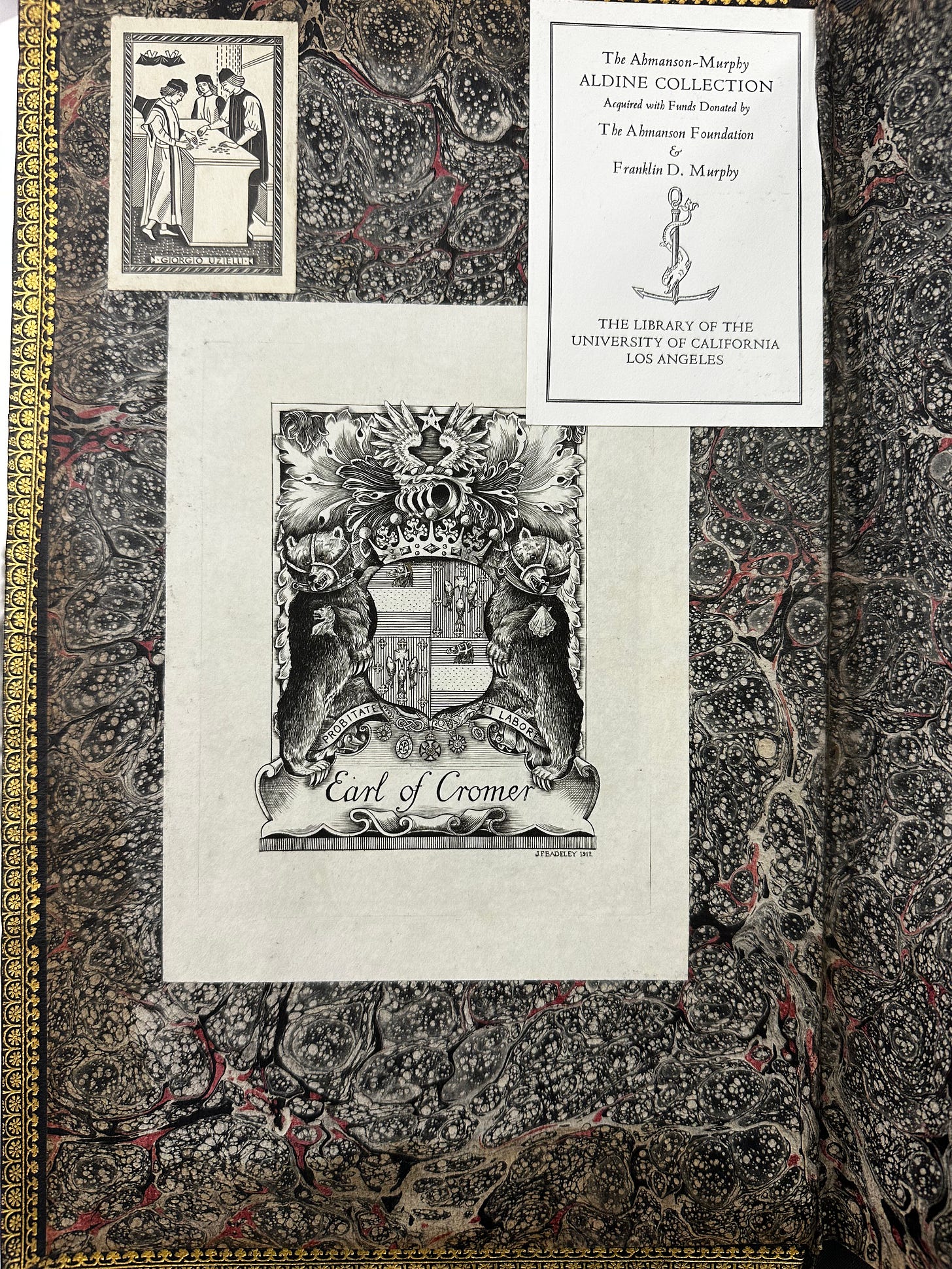

As you can see in the picture above, there are 3 bookplates:

Upper right: indicates that it is now part of the Ahmanson-Murphy Aldine Collection at UCLA. This one is obviously the most straightforward.

Center: the personal bookplate of Evelyn Baring, the first Earl of Cromer (1841-1917).

Upper left: the personal bookplate of Giorgio Uzielli (1903-1984)

There is also a fourth attested owner, according to the book: John Clement, an English physician and intellectual born sometime in the 1490s. Clement did not affix a bookplate to the Aldine Plato, but in faint and almost entirely erased letters it is possible to discern the words “This book belongs to John Clement, given as a gift by Clement’s daughter, Dorothy” (Liber Joannis Cleme[n]tis dono dorothaeae Cleme[n]tis) on the inside cover of v. 1.

Solving historical mysteries

I love this set of volumes because the book itself is so revealing about its own history. It was a lot of fun to track down all these names and start to piece together the ownership record for the book.

Part of creating an ownership history involves actual historical documentation, and sometimes you have to infer the rest—I could be right or wrong, but I always think it’s worth a try! For example, in the case of John Clement:

Records note that Dorothy was a “Poor Clare,” or Franciscan nun, in Louvain, and Margaret joined a convent as well; Winifred was married at age seventeen to William Rastell, an English lawyer, in 1544, although she died young in 1553; nothing is known of Thomas. If indeed Winifred was seventeen years old in 1544, that puts her birth in 1527 and would thus make her the oldest child, if we accept that the Clements were married in 1526. If Dorothy was born next, her earliest year of birth would be 1528. For Dorothy to be old enough to give her father the Aldine Plato as a gift, she would need to have done so in the 1540s.

Other available evidence actually confirms this approximate window: in 1547, when Edward VI came into power in England, Clement left England for Leuven. During this period, his wife Margaret made a catalogue of the volumes in their personal library, and “Plato in two volumes” is listed, in addition to a five-volume Plato. Although the list does not specify whether the two volumes were an Aldine edition, I think there’s no reason to believe that it does not refer to the edition under consideration here.

The Earl of Cromer

The story continues. After the death of John Clement in 1572 in Mechlin, where he was buried, the ownership of the Aldine Plato becomes unclear again. Due to the intellectual interests of his four or more children, it seems probable that it was kept in the family for at least another generation or two, if not longer. Its next confirmed owner was Evelyn Baring, the first Earl of Cromer (1841-1917). Cromer was an involved participant in British political life and administration of its unofficial presence in Egypt.

There is much to be learned simply from looking at Cromer’s bookplate, which appears on the inside front cover of both volumes. The bookplate takes up much of the inside cover, and is placed directly in the middle, projecting a strong sense of possession of the book. In contrast, the other two bookplates, for Giorgio Uzielli and the UCLA Aldine collection, are by necessity much smaller, and indeed Cromer’s bookplate is so large that the UCLA bookplate slightly overlaps with it and its top-right corner. It is as though Cromer envisioned himself to be the book’s only owner, in perpetuity. The words Earl of Cromer feature in a large, cursive font at the bottom; Cromer clearly chose to have his title displayed to the exclusion of his personal name, which further implies that the book is the possession of not only himself, but any future descendent (who would also be a Lord Cromer).

The iconography of the bookplate is also striking. The detail on the image is incredibly high. Right above the words “Earl of Cromer” is the family’s crest, which has a Latin motto: Probitate et Labore (“with integrity and hard work”). The two bears on either side of the crest are wearing muzzles. The one on the right has a small lion’s head insignia on its body, while the one on the left has a seashell. This imagery suggests that the family was one with dominance over land and sea, while the crown at the top of the crest indicates monarchal approval. The star and wings at the top of the bookplate could have religious significance.

It’s important to note that Cromer was very much a British imperialist and sought inspiration from ancient empires when participating in Britain’s own empire-building agenda. Cromer viewed himself first and foremost as a humanist, and was interested in the principles of Stoicism; a Christian empire, Cromer believed, should conduct itself according to a certain moral code. He was, for instance, opposed to the idea of slavery (he even criticized the Romans for their practices regarding slavery). When it comes to Plato, I think maybe Cromer would have been especially drawn to the Republic for its exploration of an ideal society. The question of the problematic nature of both Plato’s imaginary Republic and also Cromer’s real-life imperial ambitions in Egypt are matters for another time.

Ultimately, Cromer’s relationship with his Aldine Plato was a close but complicated one, and represented many of Cromer’s sociopolitical hopes and ambitions, even when these worldviews were shaped more by Cromer’s own preexisting assumptions than by classical philosophy itself.

Giorgio Uzielli

After Lord Cromer’s death in 1917, the volumes found their way into the hands of one Giorgio Uzielli (1903-1984), an Italian banker and bibliophile born and educated in Florence and Pisa. He lived in New York City for much of his adult life owing to the anti-Semitic laws of early twentieth century Italy. Little is known about Uzielli personally, and one of the most complete biographies appears to be written by T. Kimball Brooker for Grolier 2000, a collection of biographies of prominent Grolier Club members.

On the bookplate, three men wearing long robes and caps stand on either side of a counter, counting out money. The bookplate’s iconography seems to be an adaptation of a fifteenth century woodcut from Florence, a nod to both Uzielli’s profession and his country of origin. The vast majority of Uzielli’s collection was Aldine editions, with most dating to the early sixteenth century. This Aldine Plato is therefore representative of Uzielli’s particular collecting interests. I couldn’t determine why Uzielli parted with the two volumes in the mid-1960s; he did not stop collecting Aldine editions until 1974, but, as noted above, UCLA acquired both volumes in 1964.

Thank you for reading this week’s newsletter!

A lot of the time, historical details and footnotes remain elusive, but in this instance I was able to piece together quite a bit more than I thought would be possible. It was exciting to take a look at this edition almost on a whim and quite unexpectedly stumble upon a wealth of information that almost feels, to me, like discovering a secret. You never know what you’ll find in an archive or Special Collections reading room!

Thank you so much again for reading this week’s editing of Reading Art. As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts. Take care until next time.

MKA