Unicorns

In this week's newsletter, I'll be talking about unicorns and their near-universal appeal. This one's for the horse girls.

Welcome to this week’s edition of Reading Art!

This week, I want to take a closer look at the figure of the unicorn in art, which is one of my favorite mythological creatures. Unicorns are everywhere, and their depictions range from cute and friendly characters for children to somewhat more sinister dragon- or goat-like creatures, and, as we will see, they can be morally ambiguous creatures! While the unicorn is often associated with purity and benevolence, the unicorn’s appearance and other qualities are quite variable, and it is often up to the viewer of the piece to interpret the creature and its motivations.

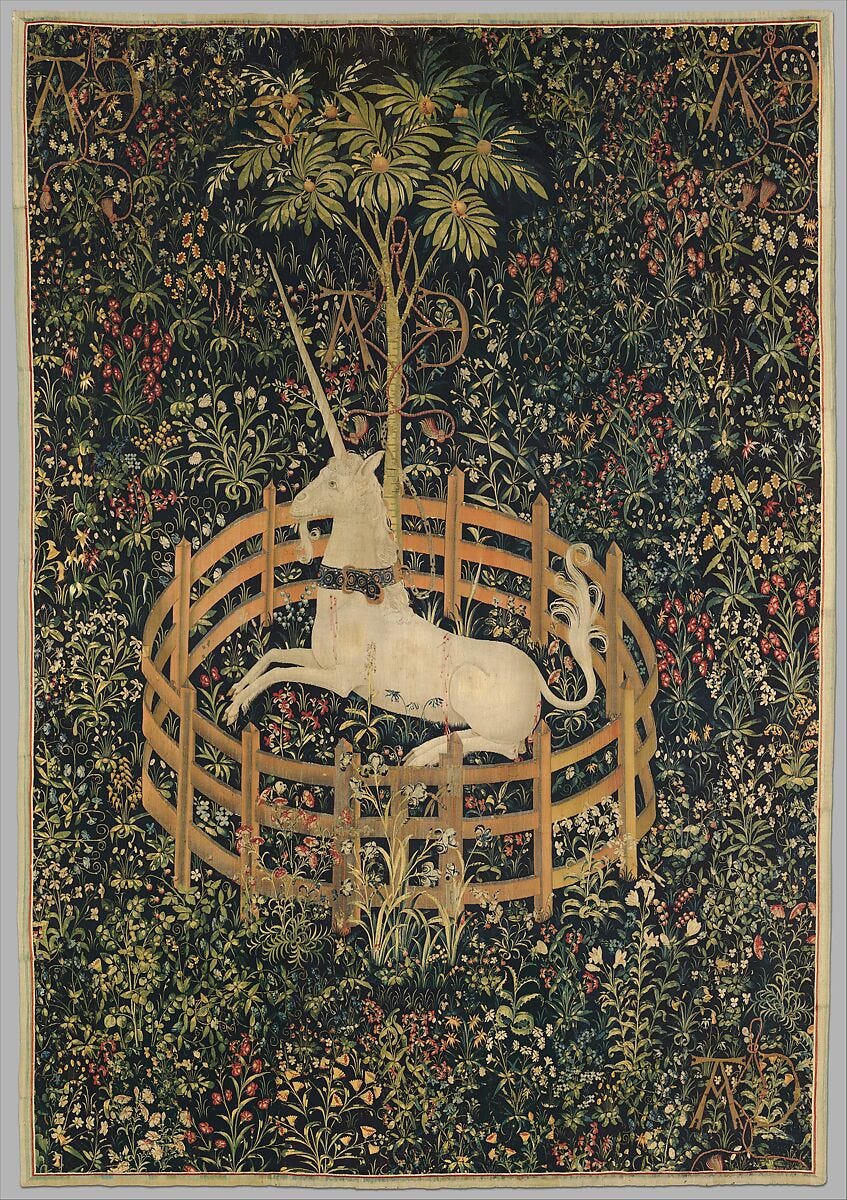

In the example below, one of the famous early sixteenth-century Unicorn Tapestries from the Met, the unicorn is contained in a fenced area—but is he on the verge of jumping out and running off? Even in this tranquil setting, there’s something inscrutable about the unicorn. But let’s look at some other examples for comparison.

I’ve always loved a unicorn, and really any kind of mythological animal. I’m pretty sure Princess Twilight Sparkle of My Little Pony fame is still kicking around in storage somewhere (core memory). So it’s really no surprise that I gravitated to classical mythology in college and then wanted to go for the PhD.

As a classicist, there have been plenty of opportunities for me to study mythical creatures, ranging from the winged horse Pegasus to much more terrifying examples, such as the hydra, a multi-headed serpent. But it wasn’t until I joined the first cohort of students for the Graduate Certificate in Cultural Heritage Research, Stewardship, and Restitution at UCLA’s Costen Institute of Archaeology (also known as the Waystation certificate) that I had the time and interest to pursue the subject of mythological creatures in any great detail. This was also the first chance I’d had as a graduate student to conduct research on non-Western art and culture, since my PhD topic had demanded most of my time up to that point.

The Waystation Initiative at UCLA aims to organize and facilitate “the voluntary return of international archaeological and ethnographic objects to the nation or community of origin,” which means that it takes in objects with no provenance history, or ownership record, and which therefore cannot be donated to museums. In general, museums have strict guidelines for acquisitions and the purchase/ownership history of a given object must be clearly documented. But this isn’t necessarily the reality for many objects, which is where the Waystation comes in. Now in its second year, the goal is for UCLA students to conduct materials analysis and provenance research on the objects temporarily housed at the Waystation. When this work is complete, the objects will be returned to their country of origin, in collaboration with the appropriate parties depending on the country or community in question.

The “Bronze Unicorn” from the Waystation Initiative

For my certificate, I was assigned a group of objects from the collection of the late businessman and art collector Lloyd Cotsen to study for the year. My favorite one from my focus group is fondly known as the “bronze unicorn,” a bronze (or, to be more precise, copper alloy) figurine of a horselike creature with a detachable horn and a long tail, which also detaches.

The Waystation has an agreement with Shandong University in China to repatriate the unicorn and a wide array of other cultural heritage objects at a future date. My research of this particular object remains incomplete: nothing is known of it before 2005, when Lloyd Cotsen purchased it from art dealer Mehmet Hassan at New York Asia Week. Documentation accompanying the unicorn at the time of its purchase asserted that it dated to the Han Dynasty of ancient China (206 BCE-220 BC), a time of resurgent interest in antiquarianism and intellectualism on a societal level.

The unicorn seems to have undergone modern repair or embellishment at some point—it would be fairly unlikely that an ancient pigment would appear neon orange. Materials analysis suggests that the copper alloy used to craft the unicorn could indeed date to the Han Dynasty. The tail and horn, however, are almost certainly modern replacements. Although it’s probably best to categorize this as a pastiche object, this unicorn coheres with other examples from the time period as well.

Unicorn or unicorn-like statues from ancient China are not uncommon, and were popular during the Han Dynasty, especially in the Gansu Province. They are probably connected to the mythological qilin, which are horse or bull-like figures who are said to appear around certain significant events. For example, one was said to have appeared at the birth of Confucius, one of China’s foremost philosophers and sages, and possibly at his death as well. In most accounts, the qilin is described as having a scaly body, almost more like a dragon than a horse.

This object in particular seems unfinished somehow; there are no details on the face, and the feet are also in a semi-unformed state as well. The extreme curve of the neck perhaps suggests a mane; in its current state, the unicorn has only one ear, which sticks out perpendicular to the neck. It is almost as though this unicorn/qilin were still emerging from the artist’s imagination, left in limbo to be “completed” by the viewer’s. It reminds me of some ancient theories of sight and imagination, that the things we imagined were hybrid images composed of things we had seem and made into new combinations to produce the fantastical. With the Waystation unicorn, it seems not so much that the process of imagining has been interrupted or broken off as it does that the viewer is invited to take active part in the process of creation. Possibly, an object of this type was a funereal offering, so the fine details were not overly important—what is important is that it evokes the idea of the qilin/unicorn/mythical creature.

Unicorns elsewhere

It seems like just about everybody loves the idea of a unicorn, and they appear in the mythologies and/or iconography of numerous cultures. For example, single-horned unicorn-like creatures appear in South African rock art that predates any kind of contact with Europe or Asia. While these creatures, like the Chinese qilin, have little to do with what we might think of as the stereotypical “unicorn” from (Western) pop culture, colonizers have been eager to conflate the creatures they observed with the European notion of a unicorn (e.g., see more here regarding the San example in particular).

There are some certain similarities, however. It seems that unicorn-type animals are either themselves benevolent or are the heralds of important events, like the qilin. In the European tradition, they were associated with virtue and chastity, particularly when it came to women.

Yet the unicorn figure is not always a docile or kind creature. When I consulted on the unicorn with a PhD candidate from Shandong University, who graciously shared his expertise, he suggested that this creature could possibly be linked to the 獬豸(Xie Zhi) in ancient mythology. This creature has a horn on its forehead, which it uses to point to guilty parties. Sometimes, allegedly, it even executes the guilty with its horn. However, the prevalence of unicorn figurines found along the Silk Road suggests that their mythological inspiration may be less specific than that. Still, it’s interesting to think about, and it’s true that in the case of ambiguous objects like these our own associations often have to fill in the gap.

Even in the western tradition, unicorns are not always very nice. In Albrect Dürer’s 1516 etching “The Abduction on a Unicorn,” the artist depicts a unicorn-like figure being used to abduct a woman. Her identity is unclear, as is that of the man, but scholars have suggested that the scene depicts the Greek god Hades, god of death, and Persephone, a minor nature goddess, as he drags her down to the Underworld so that they can be married. (Eventually, Persephone would be allowed to return to the world above for half the year.)

The unicorn here really looks more like a satanic goat, and its curved horn looks more weapon-like than those of other unicorn examples. In this instance, the unicorn is complicit in the violence of the scene. Thus, while the benevolent unicorn might be the more “canonical” or stereotypical version of the creature, its characteristics, motivations, and even appearance varied drastically.

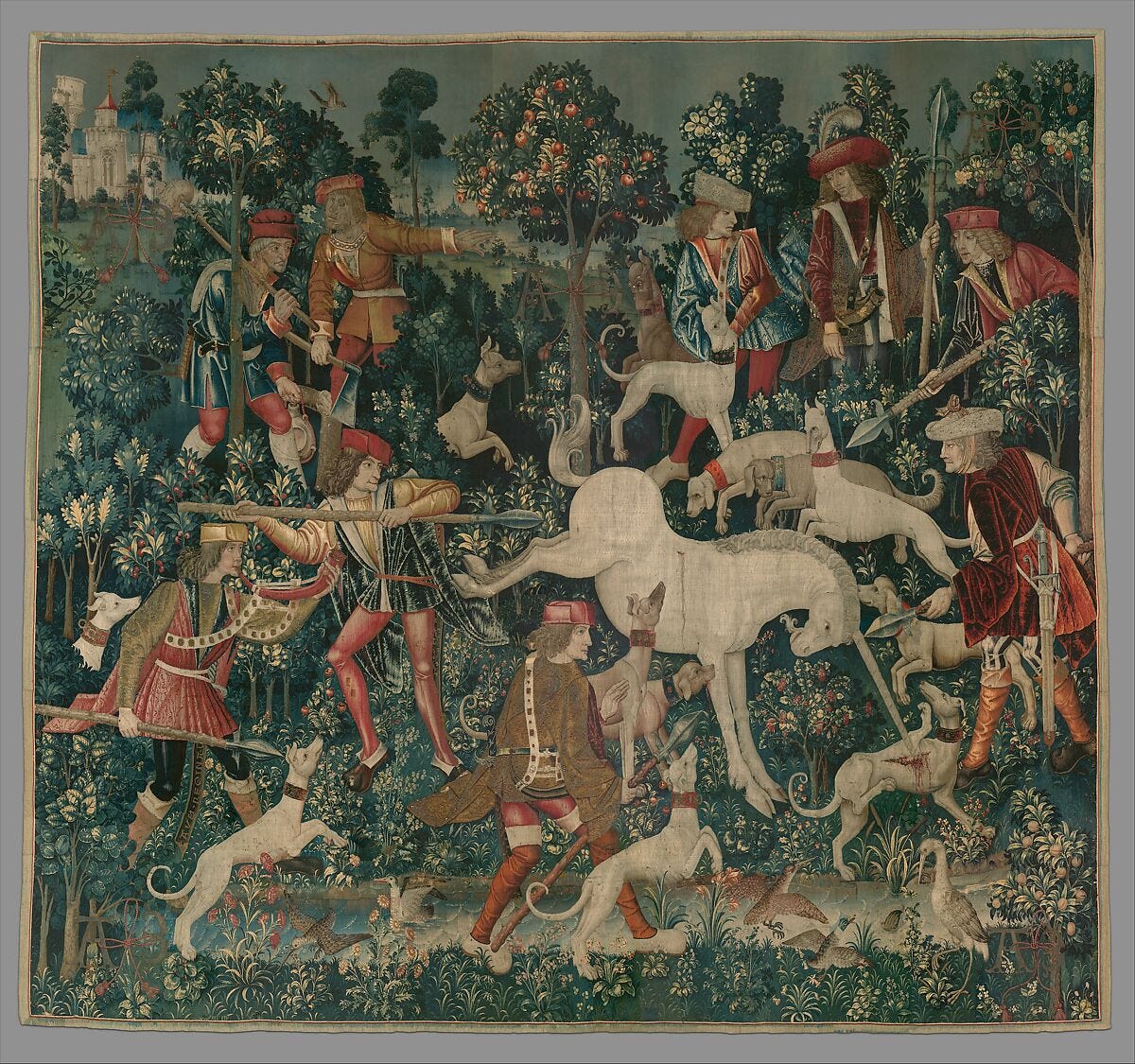

Even in the serene and charming Unicorn tapestries from the Met, one of which we saw above, the unicorn has a fearsome spirit. In another of the tapestries, The Unicorn Defends Himself, the unicorn can be seen using his horn to defend himself from the men and dogs who are attacking him. He’s gored one of the dogs, and the artist depicts the blood gushing from what would surely be a fatal wound.

As the description states on this tapestry’s webpage, one of the hunters has a scabbard inscribed AVE REGINA COELI, which means “hail, Queen of Heaven.” In European art, the unicorn is sometimes associated with Christianity and with Christ specifically. So what does it mean that the unicorn is battling against those who seem to expressly identify themselves as Christians? Once again, the unicorn is difficult to pin down. Perhaps the point is that the unicorn can be benevolent, but we shouldn’t assume that it is a passive, docile creature—potentially a reflection of Nature itself.

Thank you for reading!

Thank you for reading this week’s edition of Reading Art. As ever, I’d love to hear your own interpretation of the ambiguous and often morally-grey unicorn figure. Take care until next time.

MKA