Reading Art

Welcome to the first newsletter of Reading Art! In this newsletter, I describe the practice of reading art and also throw in some Epicureanism. Thanks so much for reading, and enjoy the newsletter.

Welcome to Reading Art

In the Central Garden at the Getty Center in Brentwood, CA, there is a portion of the walkway inscribed with a short poem or invocation by Robert Irwin, the garden’s designer. This invocation reads as follows: Ever present / Never twice the same / Ever changing / Never less than whole. These words invite the garden’s visitors to consider the simultaneous permanence and ephemerality not only of nature, but of virtually everything we encounter in our lives. From day to day or season to season, we may experience the garden in a completely different way; we and the garden alike are both unaltered and constantly in flux, and these subtle or pronounced shifts in perspective are significant, a marker of time and our own evolving positions as subject and viewer.

I believe that the way we experience a work of art and other cultural heritage objects in a similar manner: we and these objects alike are both ever-present and ever-changing. This inscription puts me in mind of one of my favorite pre-Socratic Greek philosophers, Heraclitus, famous for the saying you can never stand in the same river twice. There are certain things that live in the popular imagination, such as the Mona Lisa or the Taj Mahal, and we may think we know them, until one day we see them in a completely different light—whether as the result of visiting them in person, or merely looking at them on a day when we ourselves feel different, somehow, than we did the last time we looked. It is this potential to change over time and even in the course of a single viewing that intrigues me. A work of art is never twice the same.

1. On the practice of “reading” art

Fairly early on in my doctoral studies, I had the opportunity to take a graduate seminar with a curator at a local museum. As someone who primarily self-identified as a philologist, someone who studies texts and not objects, the chance to immerse myself in the material world opened up new avenues of inquiry for my scholarly work, but also in a personal sense. In one of our class meetings, I received some invaluable advice as someone who was (I now see in retrospect) in the process of evolving into an art historian: to read the object like a text, and so to arrive at an interpretation that is nuanced, based in feelings and impressions, and profoundly personal even as it is rooted in rational inquiry and rigorous research. To read art is to observe on a macro- and micro-scale, from the overall impression to the smallest of details: color, texture, gesture, expression, light, shadow, errors, fragmentation, repairs, and more. No response is too vague or too specific; no observation is too obvious or too obscure.

Taking to heart the advice I received, I found that I was looking at objects in a whole new way; I no longer had to rely on what the description of the work said; I could arrive at my own interpretation in my own time. For example, in the course of my dissertation research I was considering marble portraits of the Greek philosopher Epicurus (~341-271 BCE), founder of—no surprise—the Epicurean school of philosophy.

This school advocated for pleasure (hedone) as the highest thing to which we ought to aspire (the telos or end goal of our lives), in contrast to, for instance, virtue as the end goal. People in Ancient Rome really liked Epicureanism because, to put it briefly and probably over-simply, you were allowed to have fun and weren’t obligated to renounce your worldly possessions or do anything too extreme other than embrace pleasure as a means to cultivating ataraxia, or tranquillity. You don’t even have to worry about wrathful gods: the Epicurean deities exist in a state of happiness that is sublime and absolute—and, what’s more, in a semi-material form—and they really could not care any less what humanity does. The original Epicureans met in a place outside of Athens called the Garden, which was apparently the ideal place to meet other Epicureans and live out Epicurean principles.

Later generations of ancient Greeks and Romans also wanted to evoke the feeling of being in the Garden with Epicurus. Of course, one could read the large quantity of Epicurean treatises available, but perhaps the best way to physically invite Epicureanism into the home was to buy a statue of the school’s founder. There are a number of statues from antiquity portraying Epicurus; if you’ve ever been to a museum with ancient art, you’ve probably noticed that often times statues are simply labeled “portrait of a philosopher,” vel sim. Epicurus, however, was known for having a particularly distinctive appearance, even in antiquity, and this can make it easier to identify him in art.

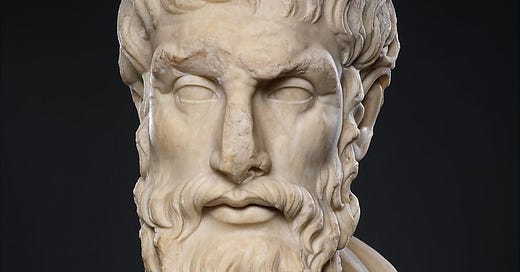

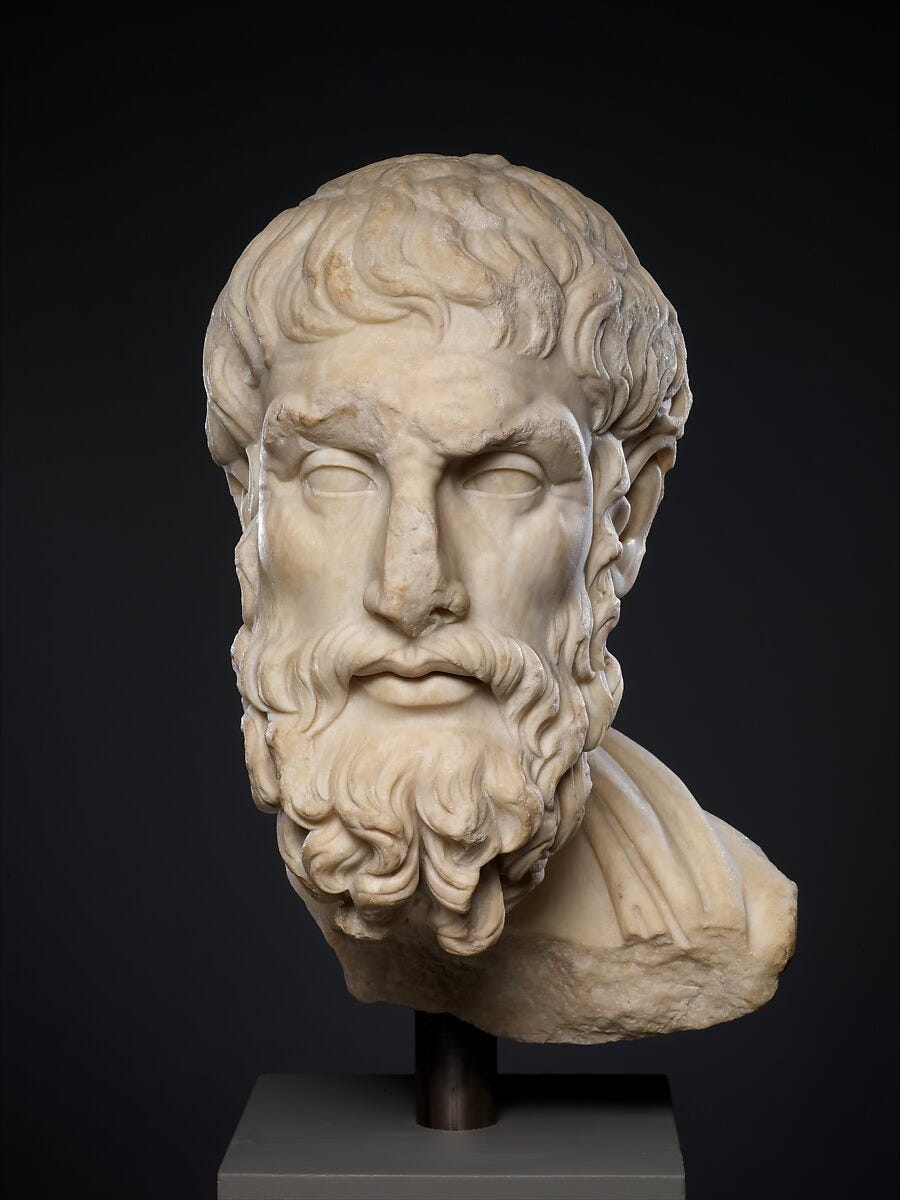

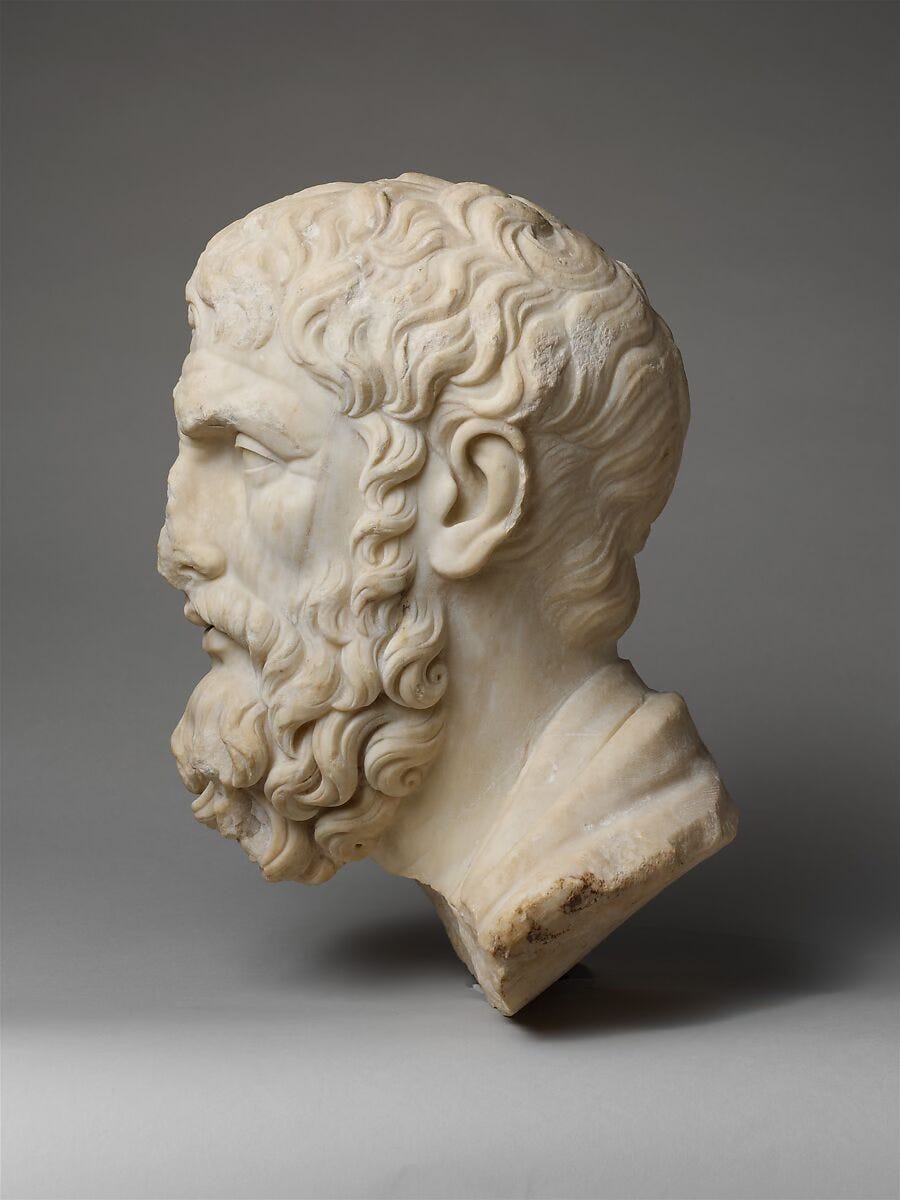

As you can see in the example below from the Met, Epicurus is known for having a thinner face, a high forehead, prominent cheekbones, and an aquiline nose—plus the baby bangs and the curly hair. The long beard isn’t too noteworthy; that’s just the standard facial hair of a philosopher. In ancient times, some people made fun of the Epicureans for caring too much about their personal appearances, which I won’t comment on, but the coiffed look of Epicurus portraits certainly suggest that he cared about the way he looked, possibly in contrast to other philosophers such as the Cynic Diogenes of Sinope, who went to great lengths in the opposite direction and was infamous for his unkempt appearance and general insistence on living in a broken ceramic vessel while he shouted at passersby to challenge their base assumptions about morality.

When I look at these portraits, I find myself focusing the most on Epicurus’ facial expression. Scholars will often point to what they see as a furrowed brow, a sign of deep contemplation on the part of the philosopher. But on Epicurus’ face I wonder if we can see any trace of tranquility, ataraxia, which in Epicurean terms was not necessarily the presence of good feelings but the absence of any bad ones. What is it like to experience Epicurean tranquility? Epicurean pleasure? Can Epicurus himself give us any insight? In many ways it is not so much what a single image can tell us, but what kinds of question arise when we see that image. How would it feel to see this portrait of Epicurus gazing at us every day, in our homes, in our gardens? What is it that draws us to Epicureanism, after all? Perhaps pursuing pleasure is not so much about what we do, but about what we let go of; Epicurus’ furrowed brow could be a sign of scholarly contemplation, but it could also be a mark of aging and the wisdom that aging confers—and, accordingly, the acceptance of mortality as a catalyst for embracing the present moment. The sharpness to his cheekbones lends his face an angularity that could betoken illness (as some ancient critiques believed), and so his Epicurean ideals would be a sign of strength in the face of poor health. Or it could simply be genetics, the way that Epicurus looked. All of this is for us, the viewers—the readers—to decide.

2. Who should subscribe?

All are welcome here, scholars and enthusiasts alike. In the ancient world, those who embraced and pursued learning and the liberal arts were known, in Ancient Greek, as pepaideumenoi (πεπαιδευμένοι), those who were “cultured” or “erudite.” While a discussion of the specific parameters of this term are beyond the scope of this post, I would love my readers to begin to also consider themselves as such, no matter where you are in the process of discovering the vast world of art and cultural heritage. Above all, I aspire to make humanistic inquiry accessible to a broader audience, and that is why I started this newsletter; in academia, what we write is generally for a very small scholarly audience, usually within one’s own field. Come and enjoy Reading Art as a humanist yourself, an art/history/archaeology fan, or as a casual observer. Think of me as your virtual museum docent or gallery educator.

As for the immediate benefits of reading art, numerous studies over the past decade have established links between viewing art and improved focus, concentration, mental health, and even emotional intelligence. Even better, some studies suggest that you don’t even have to be in the presence of the work itself—although I’ve found making trips to see things in person has always been well worth the effort, part of the reason why I’m starting this newsletter is to give readers the chance to experience some of these benefits wherever they are in the world, especially since access to museums, galleries, and archives is often restricted in one way or another.

Thanks for reading!

I’m looking forward to future editions of this newsletter and delving into the world of art, material culture, and cultural heritage with you. While I’m a scholar of the ancient Greco-Roman world by training (approx. 700 BCE-300 CE), my interests range from antiquity to the early modern period and beyond, into the modern and contemporary eras. You’ll see a little bit of everything in the coming editions.

Let me know what you’re interested in “reading” together, or your favorite work of art, or what you think of Epicureanism, or any thoughts that come to mind after reading today’s post.

Thank you so much for reading, and take care until next time.

MKA